Earlier this year, city officials called an emergency meeting on something they'd not dealt with before: They learned Green Valley Ranch residents were fighting potential foreclosures on their homes in cases brought to court by their homeowners' associations.

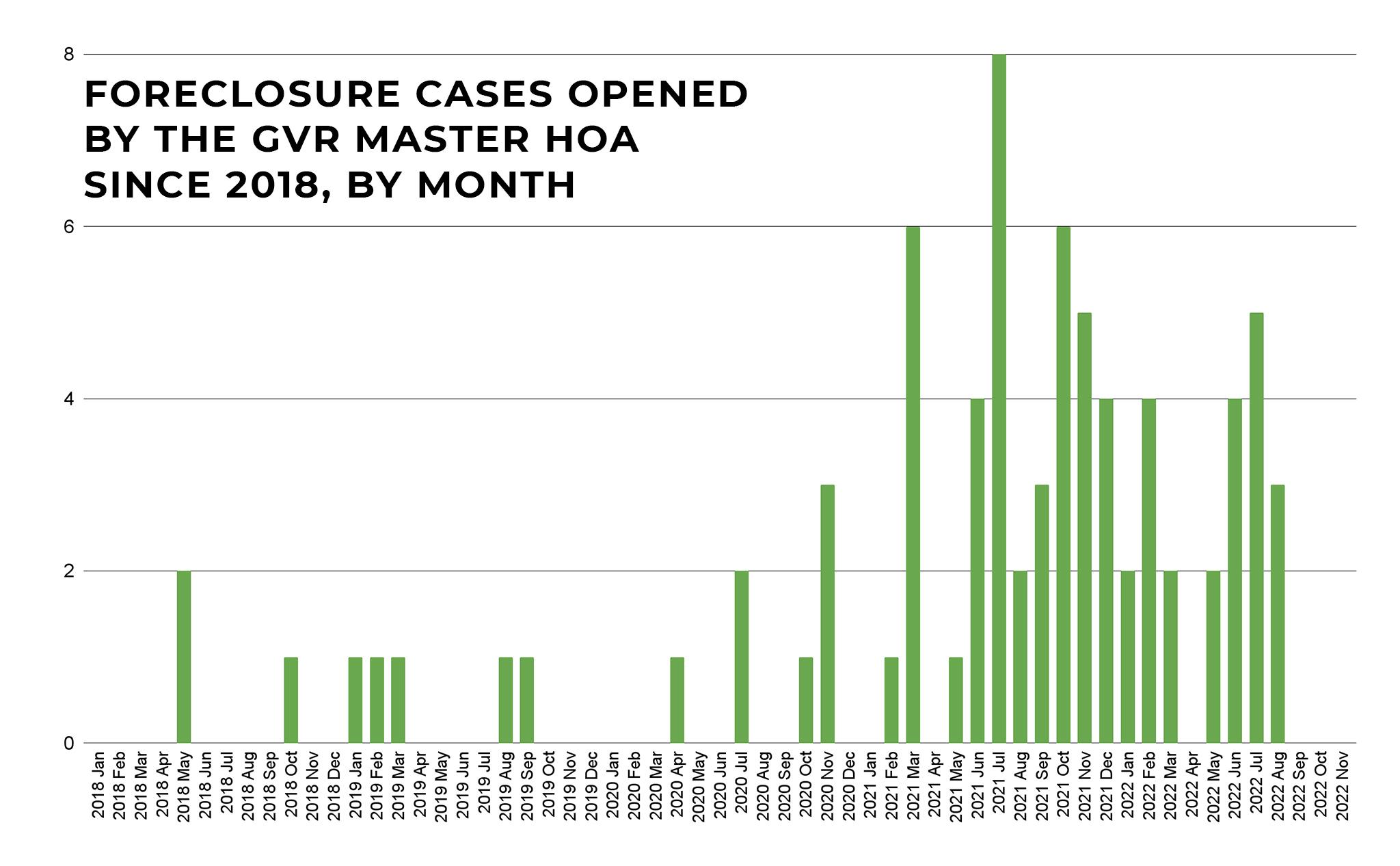

For years, Colorado HOAs had the power to pursue liens and foreclosures against homeowners who they'd taken to court over unpaid fines, a last resort to collect those payments and attorney fees generated in the process. But in 2021, the rate at which the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA took residents to court jumped significantly. City officials privately wondered if that HOA was being "predatory." Meanwhile, a statewide bill, which was drafted before the city's frenzy on the issue, advanced to the governor's desk.

In mid-August, the bill's new protections went into effect. HOAs can no longer charge residents more than $500 for individual violations, like an RV parked in the wrong place or the wrong kind of landscaping, and they were prohibited from pursuing foreclosures against residents who only had outstanding debts due to broken rules. HOAs can still try to foreclose on residents who refuse to pay assessments - which is sort of like a membership fee - but the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA collects these through taxes, so all of their conflicts with homeowners were about broken rules.

Denver Clerk and Recorder documents show the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA pursued court cases against their residents at a higher-than-usual rate into August. Once the new rules kicked in, these filings stopped altogether.

For HOAs, the new rules mean they've lost tools they need to hold up legally binding responsibilities.

Damien Bielli, an attorney with Vial Fotheringham LLC who represents the GVR HOA, told us the sudden drop in court filings is a direct result of the new state legislation. He said it reflects the fact that the HOAs, in general, have been stripped of tools they need to hold up their responsibilities to residents.

Essentially, he said HOA boards are made up of volunteers who must enforce their governing documents. If they, for example, allow someone to paint their house a color prohibited by their rules, they can be sued for a breach of fiduciary obligation.

"If the association does nothing, then the homeowner who lives next to the house (or anyone in the Association for that matter) can sue the association and its board for failing to live up to their obligations," he said, "and they do."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

So HOAs first send violation letters to try to make homeowners fix problems, then fines. If homeowners ignore those, associations take them to court to make them follow the rules and pay what they owe, usually hundreds of dollars - plus the money HOAs pay lawyers to enforce those rules, which can be tens of thousands of dollars. Bielli said the threat of foreclosure is used to recoup those attorney fees, and told us the state's new law "simply handcuffs" associations' abilities to do that.

"The Association is required to take action available to recover those funds. This is an obligation to all other owners that do follow the rules," he wrote us. "The funds expended for compliance come out of the general HOA fund that is supposed to support the community, and if they are exhausted trying to gain compliance of an owner there is nothing left to support the Association's other obligations (i.e. mailbox repair, landscaping, pools, playgrounds, sidewalks etc.)."

Regardless of legality or process, housing advocates say something needs to change.

In August, Attorney General Phil Weiser's office told us they were looking into the Green Valley Ranch Master HOA. Bielli told us that inquiry has been completed, and that Weiser's office cleared the HOA's conduct.

While the long holiday weekend precluded us from confirming this with Weiser's team, it tracks with what we've heard from officials as we reported on HOA foreclosures this year: Unless there's proof of discrimination, HOAs were allowed to pursue foreclosures in cases that began with broken rules - at least, until the new law went into effect in mid-August. (We'll update this if the AG's office gives us a statement this week.)

Still, activists who've responded to foreclosure threats in Green Valley Ranch say legality is irrelevant. On Thursday The Redress Movement, a fair housing group that's active in a handful of U.S. cities, held a press conference decrying HOA foreclosures, describing them as a mechanism of "resegregation."

"We asked the A.G. We asked the governor. Nothing really has been flagged illegal as far as what they're doing. Well, if that's the case, it's certainly immoral," Kevin Patterson, a local Redress Movement leader, said during the event. "It just shocks me to see what was happening, what was being displaced, how we continue to hear these stories."

Specifically, Patterson and his colleagues said somebody should be required to collect demographic information on future foreclosure cases brought on by HOAs, which might ensure racial discrimination would be caught and prosecuted. They'd also like to see some relief for people who've lost homes or paid tens of thousands of dollars in court already.

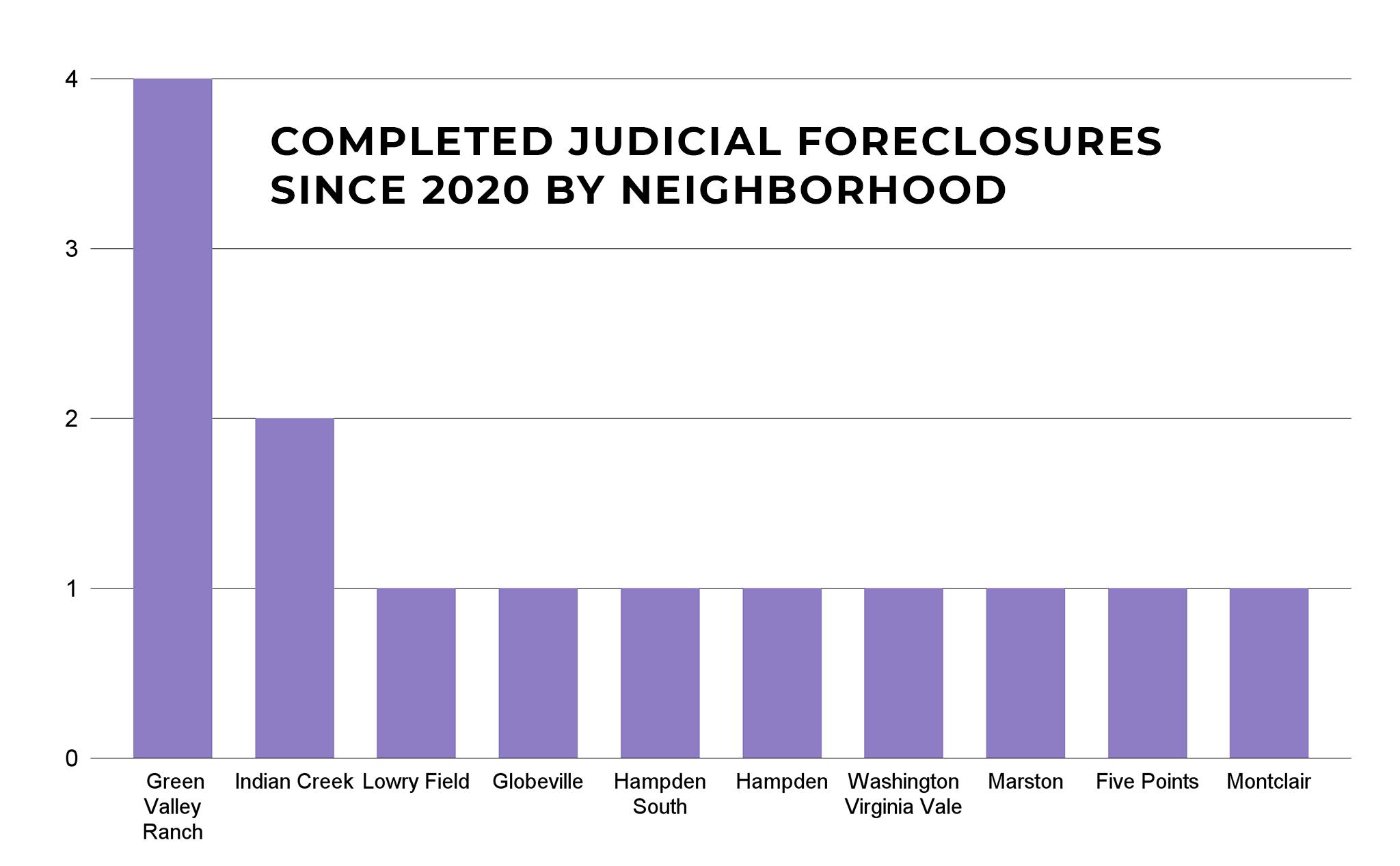

There have been 14 "judicial foreclosures" in Denver since 2020, the process by which someone loses their home in court, like during a fight with an HOA. Four of them were in Green Valley Ranch. All but two of the homes taken from owners this way were transferred to companies with names like "Buy Out Company," "Mortgage Investments Enterprises" and "Welcome to Realty 401K." Most people end up settling with associations before things get that far.

Bielli said subdivisions grappling with rule violations should think about changing their rules to avoid a cascade of unavoidable enforcement, spending and collections, but added HOA meetings don't always have the participation that their governing documents require to make those changes.

"My advice to all owners is if they want the community governing documents to change, they need to participate in their Association's governance," he wrote us.

In the meantime, he told us he's been part of conversations between HOAs, lawyers and legislators about problems with the new state law. He said he expects some "cleanup" bills will be introduced next session.