It's been a while since Jon Marcantoni felt like he connected with a politician, and he never would have thought the money he could gin up for anyone running for office would make a huge difference.

"I certainly thought, before getting to know Leslie, 'Well if you're not donating $100, $200 or $1,000 then your donations don't really matter to a political campaign," he said.

The Leslie he mentioned is Leslie Herod, the state representative running to become mayor of Denver. Last month, Marcantoni held some unconventional fundraising events for her, four nights of his play, "Puerto Rican Nocturne," which were empowered by a new fundraising system in town.

"It was a small black box theater. Our two busiest nights, we had about 25 people at each of those shows," he said. "And they were really excited."

Excited, he said, to meet Herod. Also because they learned they have a lot more power in this election cycle than in years past.

The city's spring municipal election is the first time people running for office can access a Fair Elections Fund, a nine-to-one match of small, local donations. Candidates who opt in now need a breadth of individual supporters, instead of a few with deep pockets, to maximize their campaign budgets. While the fund was initially dreamt up to help normal people run for office, it's also elevated the status of normal voters, whose $20 could transform into $180 in a jiffy.

Marcantoni said that new power resonated with the crowd.

"They got really jazzed about it, and it definitely gave them a sense that, like, we're making an impact, no matter how large or small," he said.

Here's how the Fair Elections Fund works:

Denver set aside $8 million for nine-to-one matches, which only apply to donations from Denver residents that are $50 or less.

Candidates who opted in must accept less money per donor than candidates who didn't. It's a $500 cap per donor for mayoral candidates, $350 for At-Large Council contenders and $200 for people running for district Council seats. FEF candidates also have limits on how much they can take from organizations while those who opted out have none.

Mayoral candidates need donations from 250 locals to qualify for the fund; people running for other offices just need 100.

Mayoral contenders just got their first checks from the city, bringing FEF candidates in league with one self-funded rival.

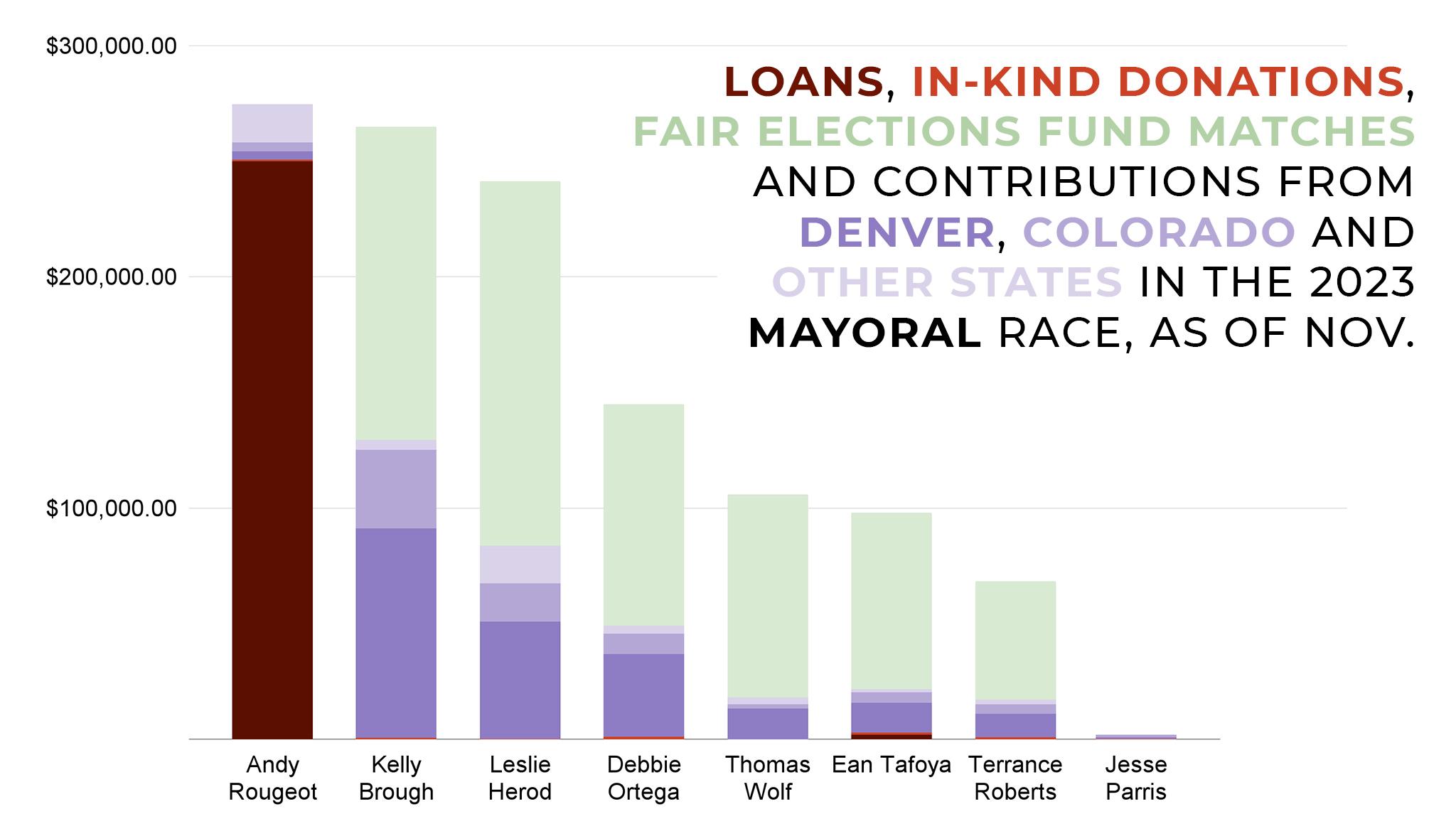

Last month, after the second filing deadline for finances, mayoral candidate Andy Rougeot's coffers soared above his competition's. The veteran and only registered Republican in the race loaned himself $250,000, opting out of the Fair Elections Fund because he feels it's a waste of taxpayer dollars.

Fast forward to this week, when Denver Elections doled out the second round of FEF matches: Candidates Kelly Brough and Leslie Herod, who were paid out $130,000 and $150,000 respectively, have almost caught him.

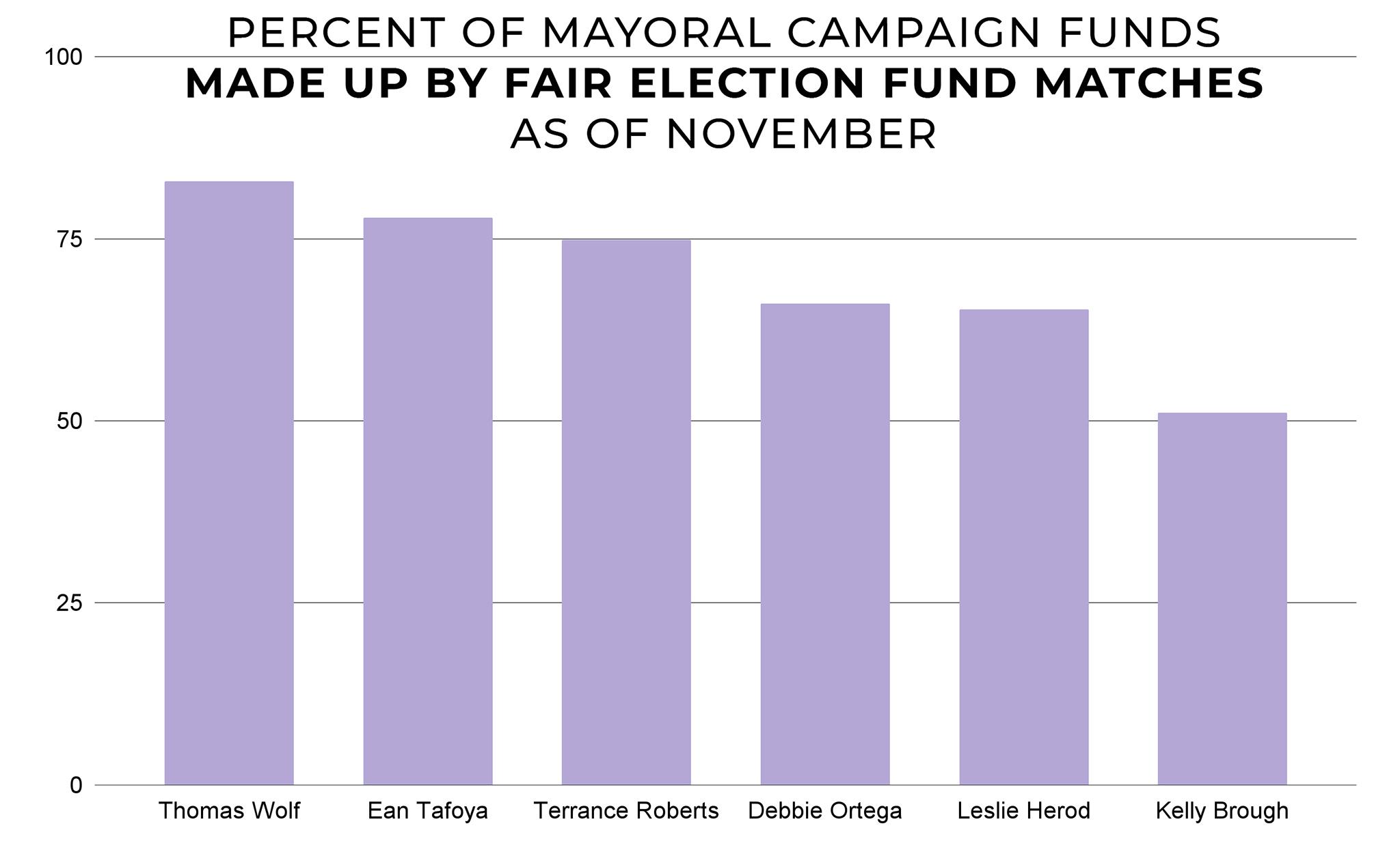

While Thomas Wolf, Ean Tafoya and Terrance Roberts did not earn as much from the fund, they've so far made the most of what it has to offer. More than 80% of Wolf's purse came from matches, followed by Tafoya at 78% and Roberts at 75%, meaning the bulk of their donations came from locals.

With so much money up for grabs, candidates may need to think differently about how they fundraise.

At a meeting with supporters last month, including Marcantoni, Herod said she may not have spent precious time at a small fundraiser like the one he threw at the small theater.

"'Puerto Rican Nocturne' probably wouldn't have been a priority for the campaign, had it not been for the match," she told us. "It wouldn't have worked four years ago - and the people wouldn't have given, because they wouldn't think that mattered either."

Instead, she's been leaning into events like those. A local DJ recently committed to spinning some benefit shows.

"That's a way she can become as major of a donor as a developer," Herod said.

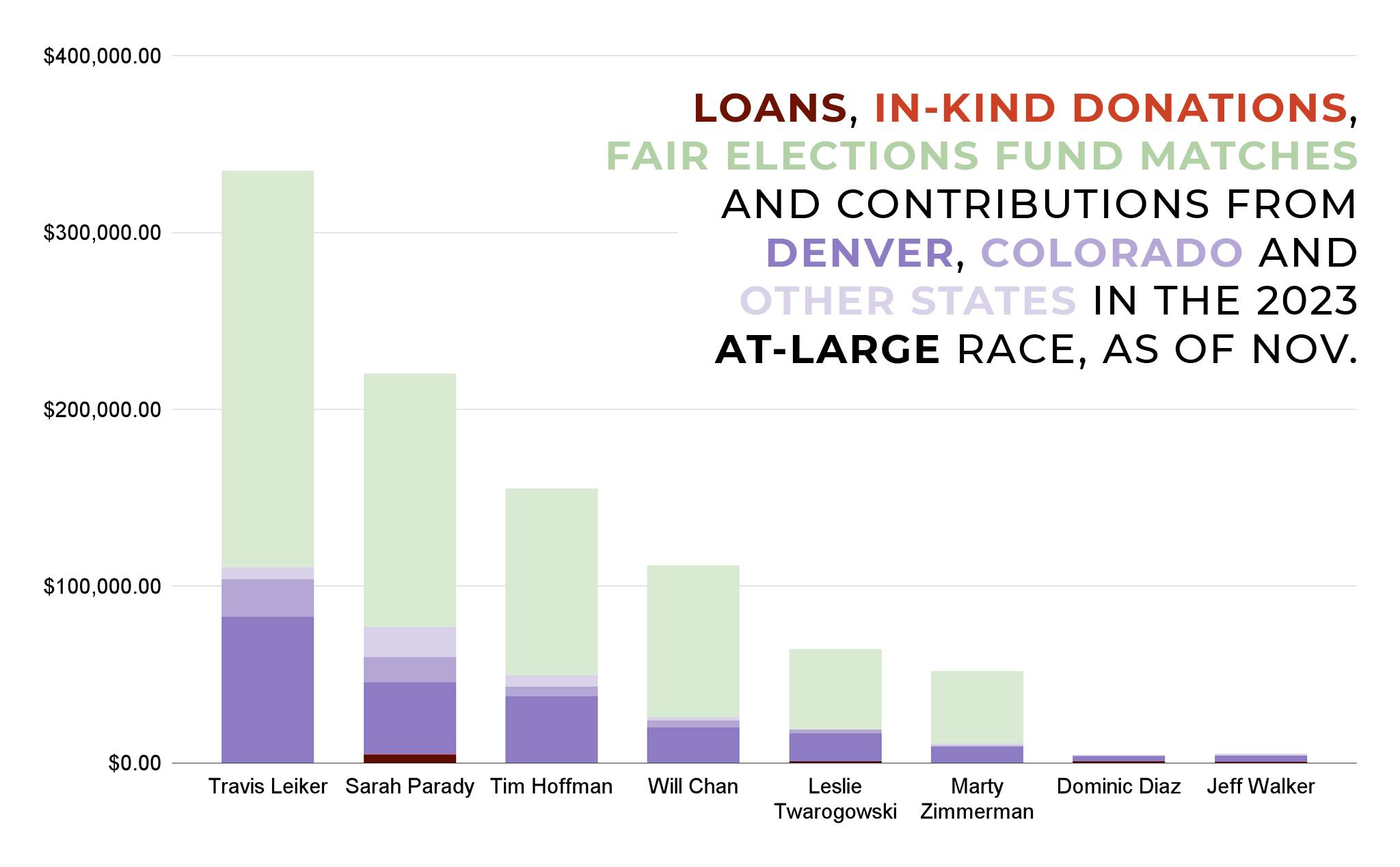

Marty Zimmerman, who's running for an At-Large Council seat, said it's "1,000% true" that everyday voters now matter so much more in this fundraising game. He's also been thinking about smaller-footprint events.

"It's happy hours at different restaurants, 'Hey, here's a chance to meet the candidate,'" kind of thing, he told us.

He's not making people pay minimum donations to come. It's better, he told us, to just get people in the door and entice them with the idea that giving an easy $50 now has a bigger impact. On the other hand, Zimmerman entered the race later than most of his competitors, meaning he's behind in gathering matching cash. FEF money is doled out quarterly, so there's definitely an advantage to get in early, if a candidate can make it happen (and not all can).

Wolf, an investment banker who brought in almost $90,000 in FEF matches this week, said he agrees with Herod and Zimmerman that it's suddenly more important to spend time with smaller donors. And now that capturing a wide base of support is what counts, he said fundraising totals will reflect overall "viability" in the race. If you've got a lot of matches, he said, it means you have a lot of people who believe in your vision.

But Wolf added he feels the fund hasn't necessarily empowered the "everyman" candidate.

"That might have been the intent, but who it really helps is existing politicians who are in office," he said. "Existing politicians have their existing donors," networks ready to be leveraged.

Brough agreed that experience running for office would be helpful running again, but said she doubts she'd have run a different campaign without FEF matches.

"The only way I ever intended to do this was meet with residents in small groups," she told us. "I've spent a lot of time in living rooms."

But the election fund don't hurt, she said, especially on a night like Wednesday. She held an "official" campaign launch party at RiNo's Blue Moon brewery, which was filled with people ready to hand potentially-matchable checks over to her campaign.

Correction: This story originally flipped the Fair Elections Fund payout amounts that Leslie Herod and Kelly Brough received.