This year, Denverites are choosing from 17 candidates competing to run the city.

Historically, Denver mayors are tough to unseat and rarely serve fewer than three terms, unless they choose to move on. So picking a mayor is a likely long-term decision.

But it's also urgent.

Many types of crime are up. So is homelessness. And evictions. Housing prices and rents have risen dramatically, and many long-term Denverites can't afford to stay. The school board has been considering shuttering schools, enrollment is down and the district is facing millions in budget cuts.

Largely Latino and Black neighborhoods in northeast Denver suffer from industrial environmental contamination, including pollution from nearby Suncor's Commerce City's Refinery and I-70.

A mental health crisis is exploding on the streets. The opioid crisis has worsened as fentanyl use has spread and deaths skyrocketed. Issues once concentrated in the core of the city have spread across all 78 neighborhoods, even as downtown struggles to bounce back from the pandemic.

Yet Denver's cultural scene has boomed.

The sports and food scenes are thriving. The population has grown, and newcomers have arrived with fresh energy and ideas. The number and types of businesses have expanded. And companies are relocating to the city, seeing endless possibilities and proximity to nature.

Huge developments in the city center could more than double downtown's population. The city is expanding east toward the airport as well.

We caught up with four of Denver's former mayors to get their take on how voters should pick their next CEO.

Here's what we learned.

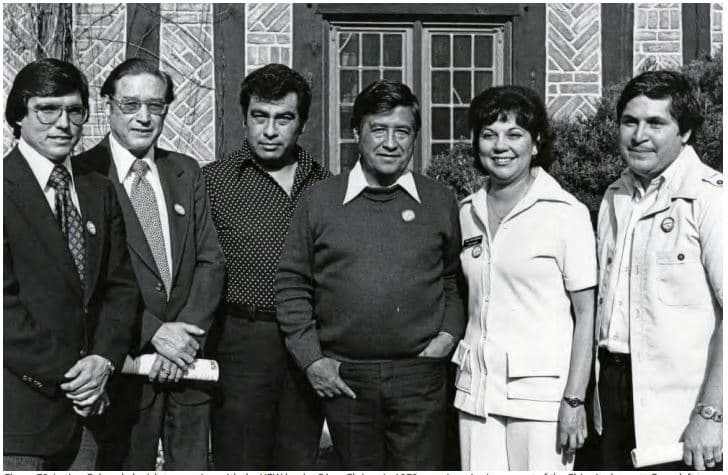

Federico Peña (served 1983-1991)

Mayor Federico Peña, a transplant from Texas, was an energetic underdog candidate who shook up Denver's political system when he defeated incumbent William Henry McNichols Jr. who had served in the role for 14 years.

While previous administrations had been run by aging white men -- in fact the classic book on Denver's mayors before Peña was titled "The Old Gray Mayors of Denver" -- he brought an energetic, young, multi-racial coalition to lead the city, bringing life back to what had become a smoggy cowtown.

"First, a mayor has to have a vision for where that mayor wants to take the city in the next 10, 15, 20 years," Peña told Denverite. "A mayor then has to have components, actions, strategies that collectively support that vision."

His vision was summed up in the slogan "Imagine a Great City."

At the time he took office, downtown was dead. The city's airport was a wreck. And Denver lacked a convention center.

Peña printed out 23 position papers on how to tackle the city's big issues. He had a plan to improve air quality, bring Major League Baseball to town, build a convention center and new airport, reduce crime and redevelop the Central Platte Valley.

That kind of specificity is something he believes worthwhile candidates need to have.

"The reason that was so unique and important was I believe that voters were very intelligent, and they wanted specific solutions," Peña said. "The old days where someone ran for mayor and said, 'I'm going to fight crime, end-of-story' -- are gone. You now need to be very specific."

While the details he pitched on the campaign trail shifted (for example, the airport did not wind up at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal), much of what he imagined when he pondered a great city came true -- some while he was still in office and some long after he left.

Carrying out his legacy projects has been one of the tasks of every Denver mayor since he held office.

But imagining a great city is just one of the jobs of a mayor.

"You're going to have tragedies," Peña said. "You're going to have unforeseen challenges. And so you have to be a cheerleader. You have to be able to rally the community when people are troubled, when they're down."

His administration saw a plane crash at Stapleton Airport, a rising gang problem, a Navy truck that dropped torpedoes at the intersection of I-25 and I-70 that shut down interstate traffic for days. There was even a tornado that lifted a truck and put it on top of a grocery store

"When does Denver get hit by a tornado?" he said.

The mayor also has to manage the cabinet and the heads of the city's departments and also establish and pass a budget.

"I think a mayor also has to continue to be involved in the community. You can't stay behind your desk," said Peña, who was a bachelor when he first came into office and came under fire from some City Council members for attending too many events.

Hiring the right people matters -- and that involves humility.

"You've gotta surround yourself with brilliant people," Peña said. "Now, I know a lot of times people will say, 'A good leader surrounds themselves with people who are smarter than they are.' And people think that's a throwaway line. It is not a throwaway line. It is absolutely true."

Hubris is also a dangerous trait for mayors.

"The day that you think as a mayor or a governor or a president or CEO of a company that you know more than anybody else is the day you will fail," Peña said.

Peña hopes the next mayor finds ways to engage both transplants and the people who live here and are at risk of displacement.

"A lot of young people who have come to the city come here with extraordinary educational backgrounds," Peña said. "They're getting the best jobs. What about the kids who were born and raised here? So when I talk about making sure this community really allows for the growth and the enjoyment of everybody, how do we make this a really wonderful place for all families, for generations to come?"

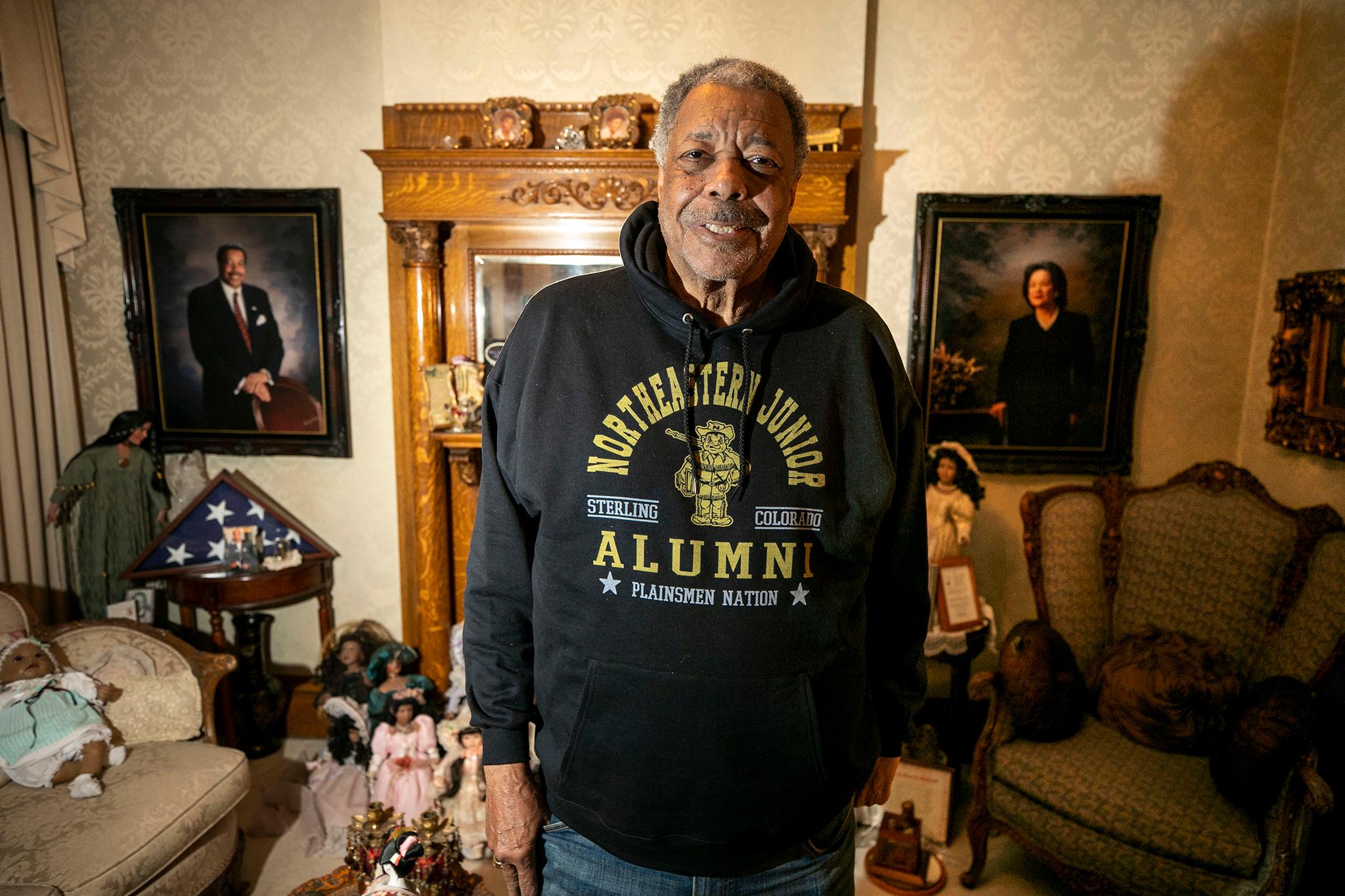

Wellington Webb (served 1991-2003)

Mayor Webb was the city's first African American mayor. If Peña, who served two terms before moving on, imagined a great city and launched many projects, Webb completed them -- along with many projects of his own.

Under his time in office, Denver International Airport opened. So did Coors Field, Mile High Stadium, and Ball Arena, which was then called the Pepsi Center.

Webb prides himself on creating more than 2,000 acres of new parks and open space. He helped develop the Central Platte Valley, where Elitch Gardens and Ball Arena were built and where the River Mile and Ball Arena development could soon rise.

More important than big projects, said Webb, is making sure the city is livable.

"The city has to be safe," Webb told Denverite. "There can only be one sheriff in town and that's the mayor."

The Blood and Crip gang rivalry that started in the '80s exploded in the '90s, and Webb saw the city through the 1993 summer of violence.

"I met with the Crips. I met with the Bloods," he recalled. "I told them, 'My gang is bigger than yours. They're blue."

Denver has again dipped in safety in recent years, Webb said.

"The one thing I know about neighborhoods and cities is if people don't feel safe, they move," Webb said. "They don't hold a meeting about it. They don't discuss it."

The job is also about management -- leading an army.

"Because Denver has a strong mayor form of government, and you got to have a vision," Webb said. "You've got to have a playbook. But you also have to have everybody that you hire -- those political appointees, they have to buy into what that playbook is. And if they don't buy in, then you made some poor choices in who you are hiring."

Webb believed in hiring a diversity of people -- and that included city employees from various educational backgrounds.

"You got to respect those city employees," he said.

After all, they're the ones on the front lines.

For him, respect meant if he heard someone grumbling about city workers at the grocery store, he'd "accidentally" bump his cart into theirs. "Normally you can catch them easier by the vegetable area," he said.

Respecting workers also meant showing up to employees' funerals when they died in the line of duty.

Sometimes the mayor has to stand up against his own departments, and that includes the City Attorney's office.

"They are not the policy maker," Webb said. "You are the policy maker. They give you legal advice. That doesn't mean you have to take it."

Denver has become younger, whiter and wealthier, Webb said, and the city needs a mayor who sticks up for everybody.

"We also have to have a mayor that's not going to forget the least of these," he said. "That would be willing to stand up, take on the big boys, if it's for the betterment of protecting a neighborhood or a class of people."

In short: "Show you give a damn about the people," Webb said.

Yes, the mayor should care about crime, affordability, housing and homelessness.

But also gas prices and groceries are too expensive. Paying for trash collection and sidewalk creation and maintenance is an unduly burden -- especially for older residents, he said. "When you start adding them up, it's a lot."

But the mayor should also care about civic pride. He's appalled he pays the highest rate possible for Comcast and can't watch Nuggets and Avalanche games on TV. He hopes a new mayor can convince the company to stop acting like "an absentee landlord" and let the people of Denver enjoy the games.

While there are many candidates in the race Webb admires, he ultimately endorsed Leslie Herod.

"Men have been running the city since the city's inception," Webb said. "And I think it's woman's time."

Sen. John Hickenlooper (served 2003-2011)

When former geologist turned brewer John Hickenlooper came on the scene, he was best known for helping revitalize Lower Downtown and arguing against the selling of the naming rights at Mile High Stadium. Even if his campaign ultimately failed and the stadium is now called Empower Field, Hickenlooper's career took off.

He had a couple of quirky ads and went from oddball with low name recognition to the winner of the '03 race.

Hickenlooper worked on regional partnerships between municipalities, creating massive projects like FasTracks, a regional train system, and multiple private-public partnerships.

Hickenlooper said there are two types of people who run for mayor: Those who want to help the community and believe in the common good and those who want power -- the chance to direct and control people.

"Despite the steps that City Council has taken in the last few years to restrict the power of the mayor, it's still one of the strongest strong-mayor forms of government in America. And the mayor still has almost total control of his budget. And I would argue that that's a good system to have, if you step back and look at where Denver and Colorado are now and how well the city has done with strong mayors in place."

That system helps attract talented people to the job, which is why 17 people have made the ballot.

"If I'm a do-gooder, this is a great place to do good," Hickenlooper said. "If I'm someone who likes power and authority, then there's a lot of power and authority."

Like Peña, Hickenlooper said good mayors should hire people smarter and more talented than the themselves.

"Excite people," he said. "Create the vision. But then you've got to implement it. You've got to manage it and make sure that it's done properly. Because even the best ideas poorly carried out crumble to dust."

Hickenlooper, who has also served as Colorado's governor and currently U.S. senator, said Denver's mayor is the most powerful elected official in the state because the person creates the budget.

But power isn't total. Mayors need to form partnerships with other municipalities across the region.

And the partnerships don't stop with municipalities. Mayors need to partner with businesses, nonprofits, and the Denver Public Schools system.

Good mayors have the same characteristics as small business owners, he said. They need to be problem solvers and innovators. They need to be empathetic, curious and humble. They need to listen well, be observational and respond. And they must connect with the community and get ideas from people on the ground.

"Progress happens when you can create the alignment of self-interest," Hickenlooper said.

And mayors can have the best plans but still be derailed by catastrophe.

"Something is always happening to disrupt the big picture," he said. A mayor needs to be able to take a 35,000 foot look and look in the grass multiple times in the same day. "A lot of people can't navigate that as easily as you might think."

Mayor Michael Hancock (serving 2011-present)

Nobody knows what being Denver mayor currently involves better than Mayor Michael Hancock, whose time in office has been bookended with economic strife and recovery efforts: bouncing back from the Great Recession in his first term and the pandemic in his last.

Hancock is the only City Council member to be elected mayor of Denver in its history. And he came into office with a good idea of how the city worked. But when he first entered the mayor's office, he had a stunning realization: He was all alone.

And as he tells it, it's a powerful position, so that is a weighty responsibility.

"Denver has a pure strong-mayor form of government as you're going to find in this country," he said. And mayors nationwide envy Denver's system.

But what does a strong-mayor system really mean to Hancock?

"You're the CEO of the city," he said. "And that's exactly how I explain it to people. You're executing and overseeing a $3 billion operation, almost 12,000 city employees, including three units that are considered paramilitary: the police, the fire and the sheriff's. You're in partnership with one of the best public-health hospitals in the country.

"And you also are in charge of the third busiest airport in the world, which has tremendous tentacles and impacts to the transportation system all over the country," he added. "So if something goes wrong with Denver, you are backlogged and are creating challenges all over the country."

Hancock has a specific idea of what he thinks voters should weigh when considering who to support.

"This is not a popularity contest," Hancock said. "This is not about how good of an activist I am. This is about managing a $3 billion enterprise."

The mayor's office, which has been around since 1933, is built to be like the Oval Office, only a little bigger. Hancock sits at Peña's old desk. He stands at his office window, looking over Civic Center Park, toward the Capitol.

"I can see the governor's window from here," Hancock said. "I often tell the governor, 'I'm watching you.'"

The next mayor, Hancock said, is going to have an economy that's confusing: Some days the stock market's soaring. Other days it's in the gutter. People are talking about downtown being dead, but applications for new developments continue to role into Community Planning and Development.

"It has to be someone who understands how to read the tea leaves as best they can," Hancock said. "And who also has the patience to study data and to lead a team to study data in order to make good decisions."

The position requires honesty and integrity, and for Hancock, that includes admitting when he's made mistakes. Two examples he mentioned: issuing a stay-at-home order to the people of Denver ahead of Thanksgiving 2020 and then flying to visit a family member, and sending inappropriate texts to an employee -- Denver Police Detective Leslie Branch-Wise.

"Before I asked for forgiveness, you'd better believe I had very hard, nasty conversations with myself," he said.

"I think people respect when people admit, 'I screwed up. And I'm sorry,'" he said. "And if you demonstrate contriteness and humility and honesty, you know what, 'What else can we say about it? He acknowledged he made a boo-boo. What else can we do?' Now if I go back and do it again, that's a different conversation. And every day of my life, I try to do everything I can to check myself."

Mayors aren't just doing their own work; they're carrying out their predecessors' projects.

"We're all still building off of what Federico did with the airport, the Convention Center," Hancock said. "We're still building off of what Wellington did with South Platte and the sports complex, right? We're still building off what Hickenlooper did with FasTracks and the arts, right? And so I accept that baton."

And that relay race that is Denver history isn't stopping when he leaves office.

"If you get someone who's on the campaign trail, 'We got to change, we got to change, we gotta change,' you know, damn well, they don't know a damn thing they're talking about. Because the awesome benefit and honor and privilege of this role is the beautiful work that the people before you have done," Hancock said. "And you will stand on their shoulders, whether you like them or not."

And whoever's next will likely be carrying out Hancock's legacy.

That means the next mayor will spend the first term completing $1.3 billion in infrastructure projects launched during the Hancock administration, including the Great Hall at the airport, partnerships with affordable housing developers, the National Western Center project and the renovation of the 16th Street Mall.

"They'll be accepting our baton, whether they want it or not," Hancock said. "Because that's what we're doing, and it takes years to complete it."