Denver mayoral candidates looked more like an audience than a panel of political hopefuls at Thursday night's Fair Elections Fund debate at Regis University.

In two hours, a whopping 16 of 17 of them covered a host of complex topics in tiny sound bites: Affordable housing, homelessness, crime, the environment, transportation, mental health and addiction.

Moderator Dominic Dezzutti did a miraculous job of keeping people on track through it all.

Candidate Al Gardner, who wasn't there, received the warmest response from the crowd. Mid-debate, Dezzutti announced Gardner was off celebrating a new grandchild born earlier in the day.

The candidates' sprawling conversation covered a host of Denver issues. Check out the full debate at CBS.

Here are some highlights on three subjects Denverite readers have told us matter: affordable housing, homelessness and crime.

On affordable housing

Candidates' approaches to the issue ranged from Terrance Roberts' idea of funding public housing through a public bank to Andy Rougeot's argument that the city needs to cut regulations and red tape and make it easier for developers to build.

Contractor candidate Robert Treta is all about making building housing more efficient. He thinks the city made a big mistake not permitting citywide accessory dwelling units.

Trinidad Rodriguez, a financier who had a hardscrabble childhood, took the first question and had a classic free-market answer.

"My vision for affordability in Denver is to start by accelerating the delivery of more different types of housing, diverse supply and more total supply," he said.

He touted his experience as one of the architects of the city plan Blueprint Denver, before Treta questioned why that plan didn't include a pathway for citywide accessory dwelling units.

Councilmember Debbie Ortega's fix for affordable housing is building manufactured homes on public land, which she said could cut building costs by 40% -- a claim candidate Thomas Wolf questioned. She touted her time on a nonprofit affordable housing development organization and gave credit to nonprofits who are building housing for people making the least money in the city.

Ortega also blasted Community Planning and Development's permitting process, which is slowing down the creation of new income-restricted housing.

Lisa Calderón argued the city needs to strengthen renters' rights -- work that's happening at the Statehouse. Those include Just Cause for Eviction legislation and the creation of a permanent emergency rental assistance program.

"The other thing is we want to keep our elders in their homes as well," she said. "We need to do something about bad-acting HOAs who are taking housing without a fair process, and we need to be able to do it without going through the court system."

Rent control, Calderón noted, is not enough. The entire system of building wealth needs to be revisited.

Jim Walsh, who's running a labor-first campaign, pivoted from talking about affordable housing and instead critiqued the broader economic system.

"The question we need to be asking is why do we have such a massive disparity of wealth in this city? Why?" he asked. "And so my efforts as mayor will be to be an ally to people who need resources, which means you need density. It means a universal basic income program that's expanded. It means a minimum wage that's a living wage -- and on and on and on."

Ean Thomas Tafoya argued the city already has affordable housing plans.

"I'm tired of the city not putting their plans into action," Tafoya said. "Consultants get paid millions of dollars every few years to come and remake a plan instead of us actually putting it into action. I want to invite you all in the community, leaders who have been doing this work, to come to the table, and let's bring these plans into action. We also need more financing."

Roberts blasted developer-owned housing and argued that city-owned housing would be better.

"For this last administration, this last four years, that's all we've been talking about is affordable housing," he said. "We need more public housing to add more stock for people who can't pay for it. We need rent controls, as soon as Mr. Polis is able to do that at the state level. We need to bring rent controls at a municipal level."

Kwame Spearman said the approach to fixing the housing crisis was to go into each of Denver's 78 neighborhoods and ask the residents how affordable housing should work.

"We need a dedicated program focused on workforce housing," he said. "If you are a teacher, a nurse, a bookseller, a police officer, a firefighter, you can no longer live in Denver, Colorado. As the son of a teacher, that's absolutely unacceptable."

He also argued the creation of housing for people making between 60% and 80% of the area median income should be subsidized by the city.

Renate Behrens wanted to fix affordable housing by turning industrial buildings and factories into apartments.

"For the young people in Denver, I would like to change the rules about indoor apartments, so that everybody who has enough ground can add one or two apartments to receive a home," she said.

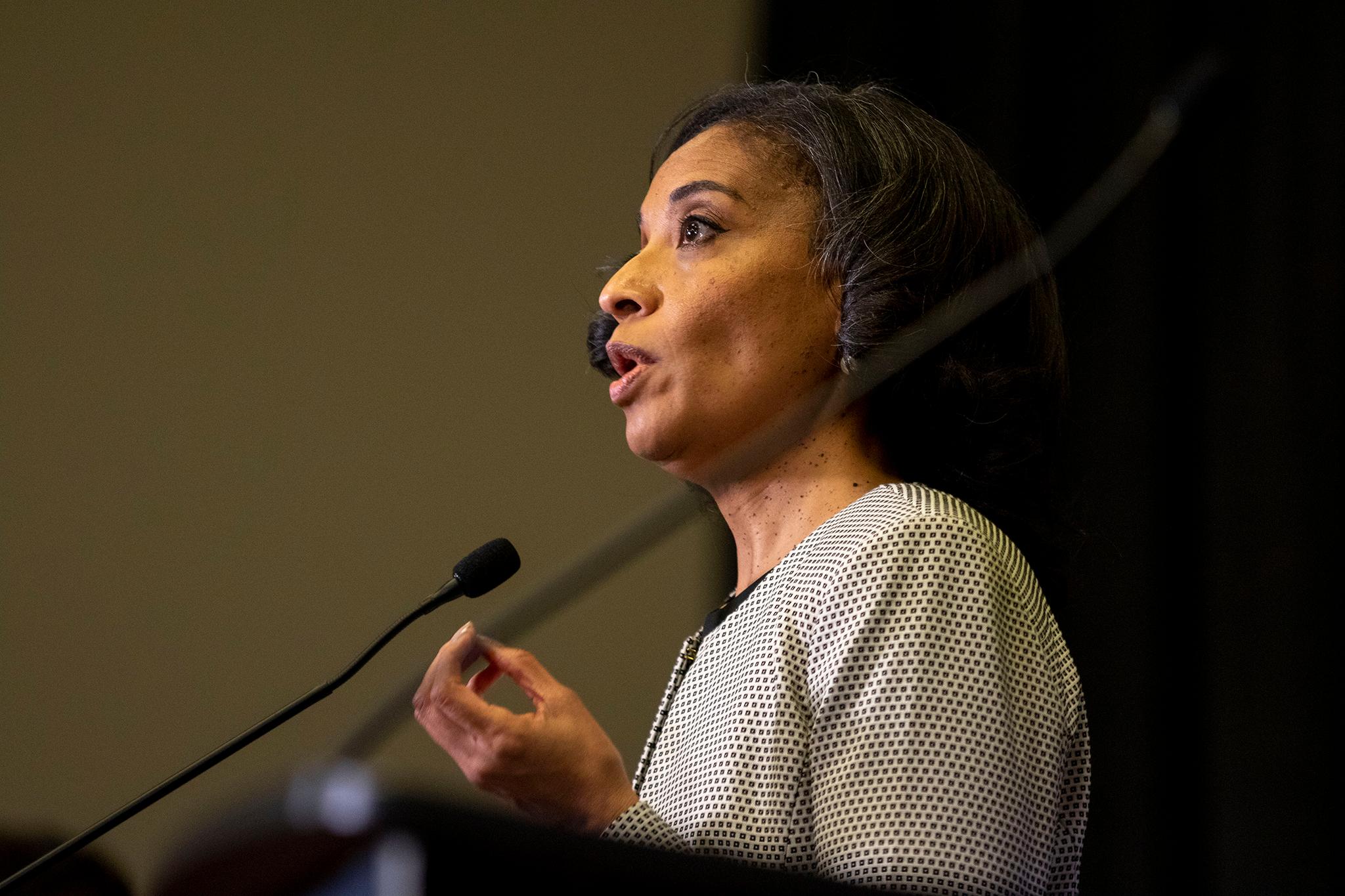

But work has already been done to make housing more affordable, said State Rep. Leslie Herod, who used the debate to note her legislative accomplishments.

"I just want to make clear that the State of Colorado has already opened the door for middle-income housing just this past year," Herod said. "I passed the middle-income housing authority at the state level to make sure we had more housing for nurses, firefighters, teachers. And additionally, we put in over $700 million at the state level into affordable housing."

Unlike mountain towns that have created communities for snowplow drivers, Denver hasn't taken advantage of the funding, she said. "It's unacceptable and we could change that."

We reached out to Herod's campaign for clarity on what money she believes Denver has not accessed. While the campaign did not offer concrete examples of funding the city missed out on, spokesperson Holly Shrewsbury pointed to a 9News story about CDOT partially funding workforce housing for snowplow drivers.

"That project was all paid for with state and fed stimulus dollars; Denver can and should do the same on public land," Shrewsbury wrote. "We must have the vision to capitalize on opportunities like that in the future, we can't miss out on fed money.

"These funds, as you know, are released to shovel-ready projects," she added. "We need Denver to come to the table ready and be creative with our public land."

Rougeot pledged to fix the permitting process and cut regulations that add costs to building new housing. He would take the influence of money and corruption out of the zoning process. He did not specify what corruption he was referring to.

"I will fight for our future to make sure people like my children can live in the city," he said.

Former State Sen. Mike Johnston argued rent control wasn't the fix for affordable housing.

"What we can do is we can build 25,000 permanently affordable units in the city," he said. "And what that means is that anybody who lives in one of those units never has to pay more than 30% of their income to rent. And that means your rent never goes up unless your income goes up."

He also championed speeding up the permitting process to a maximum of 90 days.

"We can help people get access to homeownership through down payment assistance," he said, a nod to the work he's done financing down payment assistance for Black homeowners through the Gary Community Ventures foundation's Dearfield Fund for Black Wealth.

Finally, he said his goal would be to help renters become homeowners.

"What I would do with these 25,000 affordable units that we would build is that when those renters pay their rent every month, instead of putting that money into the pockets of out-of-state investors, we actually change the financing so that money can go back into the pockets of renters," Johnston said. That money could be used for down payments, education or opening small businesses.

State Rep. Chris Hansen also argued against rent control.

"We are 40-to-60-thousand units behind in Denver right now," he said. "We are massively behind in being able to have accessible and affordable housing. And rent control in every city that it's been unused in immediately stops the creation of new supply. It stops investment."

Instead, Hansen wants to put $700 million to incentivize developers to build more income-restricted housing -- a proposal that mirrors the state's plan passed in 2022.

Where's the $750 million coming from, Roberts asked.

Hansen's answer: Using state and federal money to leverage private investment.

And yes, he wanted to speed up permitting.

Wolf said there need to be market-based solutions to reduce housing prices, and government needs to get out of the way.

"What's driving the cost is an imbalance in supply and demand," Wolf said. "There's too much demand chasing not enough supply. Supply is being constrained by a number of things." Those include the liability developers face in building new projects and, you guessed it, delays in permitting and zoning.

Former Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce head Kelly Brough also opposed rent control. Her solution? Converting downtown office space to homes and incentivizing the transition. Adding supply would help stabilize rent, she said.

"I would build on publicly owned property for-sale condos, so the missing middle, hardworking families would get the chance to own in our city and begin to build wealth again," she said.

Aurelio Martinez supported rent control, too.

On homelessness and mental health.

Through the night, Rougeot took a law-and-order approach to homelessness and crime, arguing for the enforcement of the urban camping ban to force people into drug and mental health treatment.

"When I walk to the park by my house with my three-year-old in my arms, we will see a man with his pants around his ankles using his restroom," he said. "It is not compassionate to let that happen. It's not compassionate to step over someone sitting in a tent in the streets. The compassionate thing to do is to get those people into the mental health and drug addiction services they need and in our shelter system."

Martinez said we need to hold mental health facilities accountable and close them down if they're not working.

"We have to stop thinking shelters, shelters, shelters," he said. "And we have to start thinking solutions, solutions, solutions."

Hansen argued we should take stock of the millions the city is spending on homelessness.

"This is a moment to really reevaluate," he said. "We're going to spend a quarter billion dollars -- $250 million -- this year on different aspects of responding to this crisis. And we're seeing a negative result. The numbers are getting worse in our streets, not better."

His fix? Evidence-based programming and budgeting -- which he did not elaborate on -- and enforcing the camping ban.

Wolf's entire campaign is centered around ending encampments and getting people sheltered.

Walsh took a different tact: "I think this issue has to begin with ending blaming of unhoused people for their situation. So how can we help the mental health of people that are unhoused? We can stop sweeping them. We can stop criminalizing them. We can stop jailing them. We can invite unhoused voices to tables that make policy."

Tafoya pushed creating stability, housing and continuity of care for unhoused people. That means making sure people aren't punted around the system while they are in outpatient services. Such instability reduces their ability to connect with service providers.

Ortega noted funding sources for homelessness and related issues already exist and said the city needs to ensure it is using the money wisely. She also proposed creating single-room occupancy units as part of the solution for people transitioning out of homelessness.

Brough proposed a regional response with mayors in other cities who have endorsed her plan.

"I've made a commitment to end unsanctioned encampments my first year in office," she said. "In essence, we have to stop sweeping people endlessly from neighborhood to neighborhood, and instead get them into safer locations temporarily. I'll create sanctioned camping sites until we can build the housing and shelter we need."

Spearman championed the sweeps and suggested whoever is failing to enforce them should be replaced -- that's what a good CEO would do.

"I'm a small business owner," Spearman said. "I own the Tattered Cover. Some of my employees are housing insecure themselves. We have to invest in innovation."

He also argued many unhoused people choose that life. The system isn't failing them. They want to live on the streets.

He also said the homeless advocacy nonprofits like Urban Peak, which he sits on the board of, and the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless "are not doing their job," he said. Why? The city needs to work harder to give people opportunities to get into those programs.

"We have got to clean up our streets," he said. "Our businesses, our neighborhoods are dying, and it needs to happen right now."

Calderón pointed to studies that the vast majority of unhoused people on the streets don't want to be there and implored her fellow candidates to stop blaming unhoused people.

She described keeping the camping ban as "mean-spirited" and noted that "we have 10 years of data that it doesn't work. We have the worst homelessness we've ever had."

Her solution? Replacing the sweeps with crisis intervention responders.

Herod, speaking about whether the city needs more mental health and treatment options, said absolutely and pointed to her sister's struggles as a drug user who spent decades away from her children in prison.

She then took credit for creating STAR, the Support Team Assisted Response, which provides an un-armed alternative to police when dispatchers receive a 911 call about somebody having a mental health crisis.

Making the claim that she created the program had several candidates questioning her credibility since they too and many others worked on the launch of the program. She did acknowledge it was a collaborative effort earlier in the night.

Spearman used her comments as an opportunity to blast policies she's fought for at the statehouse.

"Leslie, with all due respect, the policies that you've championed over the past three years, whether it's decriminalization of fentanyl, whether it's making a misdemeanor from a felony to steal a vehicle, don't you think that has created a culture that is in our city right now, in which more people are committing crime? They're committing violence, and quite frankly, they're engaging in homeless activity," Spearman said.

Herod's policy did not decriminalize fentanyl. It shifted the penalty for possession from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Herod clapped back at Spearman: "Well, respectfully to our CEO, underpaying his employees so that they have to go into social housing in order to live in our city, I believe that the war on drugs is a failed war on drugs."

Instead, the failure, she argued, was the "city is not providing people with the services they need."

She continued: "If we want to reduce the Fentanyl crisis and get after it, let's get people services and reduce that demand. Fentanyl is killing people today, regardless of whether it's a felony or misdemeanor. People are still using it, and they're still dying. What are we going to do about it?"

Rodriguez piled on the criticism of Herod's de-felonization of drugs: "It was a terrible idea. It's failing our people and it's tragedy."

Calderón added that not all homelessness is about addiction and drug use.

"We also need to focus on trauma," Calderón said. "When we talk about unhoused people, not everybody is drug addicted. Not everyone has mental illness. In fact, a lot of people are working people. They are in their cars. We need to expand the safe-to-park program. We need to have a continuum of options and not overly focus on the visibly homelessness."

Johnston doubled down on his commitment to end homelessness.

"No one should be homeless in the city," he said. "We have a moral obligation to make sure everyone has a place to stay. And we can put an end to people having to sleep in parks and public places. The way we do that is by opening micro-communities. We could put 40 to 60 tiny homes. I would build 10 to 20 of these around the city, where people can have built-in wraparound mental health services, addiction treatment, workforce training to get back on your feet."

On crime.

Brough's solution to crime went far beyond law enforcement.

"It's been a lot of time talking about public safety as the response to 911," she said. "And the truth is what really makes the community safe is all the other work we can do to reduce and prevent crime. We know access to economic opportunity and excellent education, stable housing, support systems and safety nets -- that really work for our community."

Martinez supported creating more youth programming.

Rodriguez, Johnston and Rougeot all planned to increase the size of the police force -- even as the department is far behind meeting hiring goals.

Calderón argued it was time to stop treating young people as gang members. She also said it's crucial to build service programs for youth between 18 and 24 where there is a gap.

Roberts, who was a Blood leader and then eventually an anti-violence organizer, argued to fight crime we need more dedicated youth centers with robust arts programming. He also said we could reduce violent crime by providing more housing, since crime is fundamentally an economic issue.

Herod argued we need to break up organized crime and car theft rings by putting more investigators into the field.

Johnston proposed creating an auto-theft unit in the police department. Ortega proposed boots-on-the-ground people ensuring young people have access to resources and services.

"We have got to start enforcing our laws," said Spearman. "We've stopped. We've had five catalytic converters stolen from our van at Tattered Cover. If we don't enforce our laws, crime continues to escalate. And now we're starting to see what happens with violent crime."

The night rolled on.

Treta claimed to have built the most environmentally efficient home in Denver, with 28 solar panels he uses to power his Tesla -- which led to a string of jokes about his Tesla.

"It's crazy that we're talking about building energy-efficient homes," he said. "I know how to do it. Just let me do it."

Tafoya, who was hit by a car while riding his bike as a child, touted his environmental record and commitment to bike infrastructure.

Denver's roads are "dangerous by design," he said, and it's time to focus on fixing the streets. Focusing on high-injury networks -- areas where many people were hurt or killed by cars -- would be a good starting point.

Behrens suggested prisoners be put to work to fix Denver's sidewalk system.

"We have lots of them," she said. "They owe us something."

She also suggested lawns be abolished and replaced with gardens.

Hansen talked about his failed efforts to pass laws against distracted driving.

Martinez argued the city needs to bring control back to neighborhoods.

Calderón argued the city needs to prioritize bringing Denverites displaced from their neighborhoods back to town.

Walsh asked the crowd if they'd heard the folk song, "Which Side Are You On?" and then asked, "Why have we never had a mayor on the side of workers in this city?" He pledged to be one.

The night ended with smiles, handshakes, and private elaborations on policy.

April 4, the last day to vote, is around the corner. With so many candidates to consider, voters are right to wonder: How will we make a pick?

Update: We added comment from Herod's campaign about state and federal funding she believes Denver is not accessing.