Before Kelly Brough decided to run for mayor of Denver, she had a conversation with her partner David Kenney.

Brough said she's been in a relationship for about 10 years with Kenney, a longtime political consultant and city and state lobbyist, whose clients make up some of the largest developers in Denver.

"We actually have talked about that," said Brough, the former CEO of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce. "Before this summer when I was trying to decide if I would run or not, David had said to me, 'I won't do any business with the city. I won't represent anyone doing business with the city, to remove any conflict.'"

Kenney's firm, The Kenney Group, has clients like Kroenke Arena Company. Kroenke aims to develop the south parking lots around Ball Arena, one of the largest tracts of open land in downtown Denver.

Kenney also represents Fulenwider, a large developer of land around Denver International Airport. The owner, Cal Fulenwider III, is a top donor to an independent expenditure committee that supports Brough.

Kenney refused multiple interview requests through his firm The Kenney Group and through Brough's campaign.

Brough, on top of leading the chamber of commerce for 12 years, served as chief of staff for former Mayor John Hickenlooper. She's been a top fundraiser since getting into the race for mayor and is running about as many TV ads as any candidate. Those resources, her experience and connections in government and business, undoubtedly make her a leading candidate for one of Colorado's most powerful jobs. Denver's strong-mayor system would give her, if elected, vast control of city government and policy.

Kenney, meanwhile, has been labeled one of the most powerful lobbyists in Denver, advising governors and mayors, and representing businesses like Frontier Airlines, Kroenke and Xcel. And he's exercised his connections in the current administration, meeting with Mayor Michael Hancock and several of his top deputies, Alan Salazar and Evan Dreyer, at least 31 times between 2011 and 2022.

And his firm has been involved in a series of successful ballot issue campaigns on behalf of the Chamber and other business interests.

Brough emphasized that she takes these issues of potential conflicts seriously, in particular with regard to Kenney.

"What's important to me, in my career, one of the things I'm most proud of, is how careful I am about these kinds of issues," Brough said. "I think what we're focused on is making sure he doesn't represent anyone where I'm in the line of authority to make decisions, and we would remove that conflict for us."

Supporters of Brough believe she can manage Kenney's conflicts.

"I think his business interests have to change, and I think they will change," said former Gov. Bill Ritter, who endorsed Brough for mayor and once employed Kenney as a campaign manager. "You have to not only avoid the conflict of interest, but even the appearance of any impropriety in that conflict of interest. And my advice, to Kelly and to David, would be to take this line and make it really bright."

Ritter acknowledged that it's not an easy thing to manage, but "one of the reasons I endorsed Kelly is that I trust her to do that the right way."

Brough's relationship and potential for a conflict stand out among the other top candidates. According to their campaigns: Councilwoman Debbie Ortega and State Rep. Leslie Herod are single; State Sen. Chris Hansen is married to the director of an education grant funding group; Lisa Calderón is divorced and wouldn't disclose more information about her private life other than to say it wouldn't pose conflicts; and Andy Rougeot's wife is a senior marketing director at Vail Resorts.

Mike Johnston's wife, Courtney Johnston, is Chief Deputy District Attorney in Denver. The District Attorney's office is run by an elected DA, Beth McCann, and it's a separate branch of city government. Still, Johnston's campaign said that his wife would recuse herself in the event that her work would overlap with a mayoral issue.

A lobbyist and a consultant

Brough said Kenney would stop any city-focused work, and that would be enforced, in part, through public disclosures.

"There's required disclosures for lobbyists," Brough said. "There's transparency in who the mayor is meeting with and what's happening."

The records the city keeps, however, are not as transparent as it may seem.

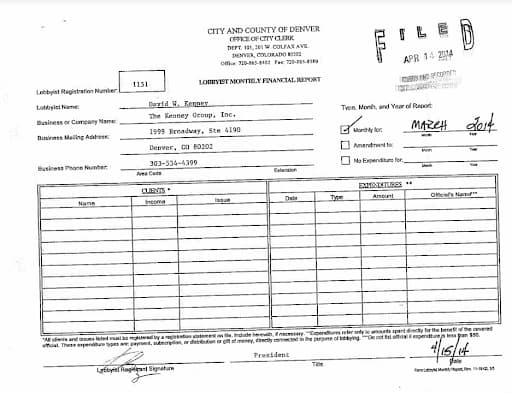

Kenney has filed city lobbyist registration forms for the past decade, but he's never listed having lobbied for any particular client.

The mayor's calendars are a public record, but require an open records request. Denverite obtained the calendars for Mayor Michael Hancock and some of his top staff covering the past 12 years.

Most of Kenney's meetings were with Hancock's deputy chief of staff Evan Dreyer, with 17 calendar entries between 2013 and 2018. Ten of the 17 meetings were in 2013, a decade ago, and Dreyer couldn't recall what the meetings were about.

Kenney also occasionally got time in front of Mayor Hancock. In 2011, not long after Hancock became mayor, there's a calendar entry titled "David Kenney, Kelly Brough, Maria Garcia Berry, Evan Dreyer re: Paid Sick Days Initiative & FasTracks."

A few months later Brough celebrated the defeat of Initiative 300, a measure that would have required Denver businesses to give workers an hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked, with Maria Garcia Berry, who runs the city's top lobby firm CRL Associates. Mayor Hancock also opposed the initiative.

In March 2014, Kenney met with Hancock again, bringing along one of his clients, Dave Siegel, then CEO of Frontier Airlines. The full entry is titled "Mayor Hancock, David Kenney and Dave Siegel re: Frontier Status/Headquarters and City's Software Tax"

Yet Kenney's lobbyist records for that entire year list no clients or lobbying expenditures.

Sean Duffy, who is a senior advisor at The Kenney Group, did agree to an interview, and he said those meetings don't meet the legal definition of lobbying, according to his boss.

"David Kenney doesn't really lobby, as a function, a core function of what he does at the firm. He's the CEO of the firm," Duffy said. "Many of the meetings that he takes with the mayor, for example, are introducing clients to the mayor, to the city, briefing the mayor on issues facing a client. And so there is, to meet the definition of what a reportable lobbying expense is, in his definition, those were not."

Duffy added: "Now whether that interpretation is a little tighter than it should be. That's an open question."

While most people might consider meeting with clients and the mayor as lobbying, Denver has a stricter definition that requires disclosure when lobbyists attempt to influence "legislative matters," which the code defines as a "bill, resolution, amendment, motion, nomination or appointment."

Duffy said they've been telling clients for months that if Brough is elected mayor, "our firm will no longer be available to do any work in front of the city and county of Denver or its agencies."

Through the Hancock years, Kenney also remained involved in local politics through city ballot issues, usually favored by the Chamber, from the Stock Show tax initiative to fighting the Right to Survive campaign. His firm has collected $178,373 between 2013 and 2019, for consulting and research on ballot issues, according to city records.

Brough also had to navigate some potential conflicts of interest with Kenney during her time as CEO of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce. Kenney was awarded work by the Chamber for election work, and Brough said she wasn't involved in that.

"I was removed from that process in the selection," Brough said. "And my [board] chair at the time would've been the person who would've run that process and made the selection."

One of Kenney's longest tenured clients is the developer, Fulenwider. Cal Fulenwider, the CEO, wrote a $50,000 check to the independent expenditure committee, A Better Denver, that supports Brough.

IE committees can't coordinate with candidates, and despite the connections, Brough said she's not at all involved with fundraising for the IE.

"I am not talking to anyone who's working on the IE," Brough said. "We're being very, very careful about that. But I can tell you I certainly know Cal myself."

A long history in Denver politics

Hickenlooper wrote in his memoir that Kenney helped propel him into the mayor's office back in 2003.

"David was a seasoned veteran of Denver city politics. He had worked with Wellington Webb, and considered Webb a mentor. He understood this political game inside and out," Hickenlooper wrote in his 2016 book, The Opposite of Woe.

Hickenlooper's co-author on The Opposite of Woe, Maximillian Potter, helped write a brief profile of Kenney as part of Denver's 50 most powerful people, for 5280 magazine in 2010. Kenney was ranked 11th, one place above Philip Anschutz.

"A pugnacious lobbyist, Kenney is the man who solves problems for Democrats in Denver- nicely, if that'll work; not so nicely, if required," reads the article. "Kenney was influential in getting Bennet appointed, and helped nudge along the process at the end of 2008 that placed Kelly Brough (former Hickenlooper chief of staff) at the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce..."

Brough said they were not in a relationship at the time. Kenney was married, and still is, to another woman. But Brough said Kenney and his wife are separated.

"He has been amicably separated for a very long time," Brough said. "I think for him and his family, what was best, is this structure. I respect it."

Given his long history advising mayors and governors, could Kenney be a sounding board for Brough if she wins and is running the city?

"No, I don't foresee a situation where he would be," Brough said. "I do foresee a situation where your partner's just helping you navigate a really hard job in the emotional impact and toll it takes from my observation. And frankly, that's been, where I've been really lucky in this campaign, because I've got somebody who probably knows, before I know, what I'm about to go through, maybe including this," referring to the interview with Denverite.