Jesse Garcia held several faded photographs in his hand. A blurred photo of him and his siblings surrounded by grass in front of short brick buildings. Another with his mom and aunt rocking beehive hairdos. And a sentimental one of Garcia in his Marine uniform being welcomed home by his uncle and role model, Henry, who was also a veteran.

"He inspired me to join the military," Garcia said. "He was the only man around, so all the boys in the neighborhood looked up to him...People know the taboo part of the projects, right, poor kids, crime, neighborhood of color. But what you can't take away from that is the value of family and friendships. Whether it was bad or dysfunctional, it was still community. You can't deny that."

Garcia, with his pictures and memories, was sharing his version of what it was like growing up in the Sun Valley neighborhood.

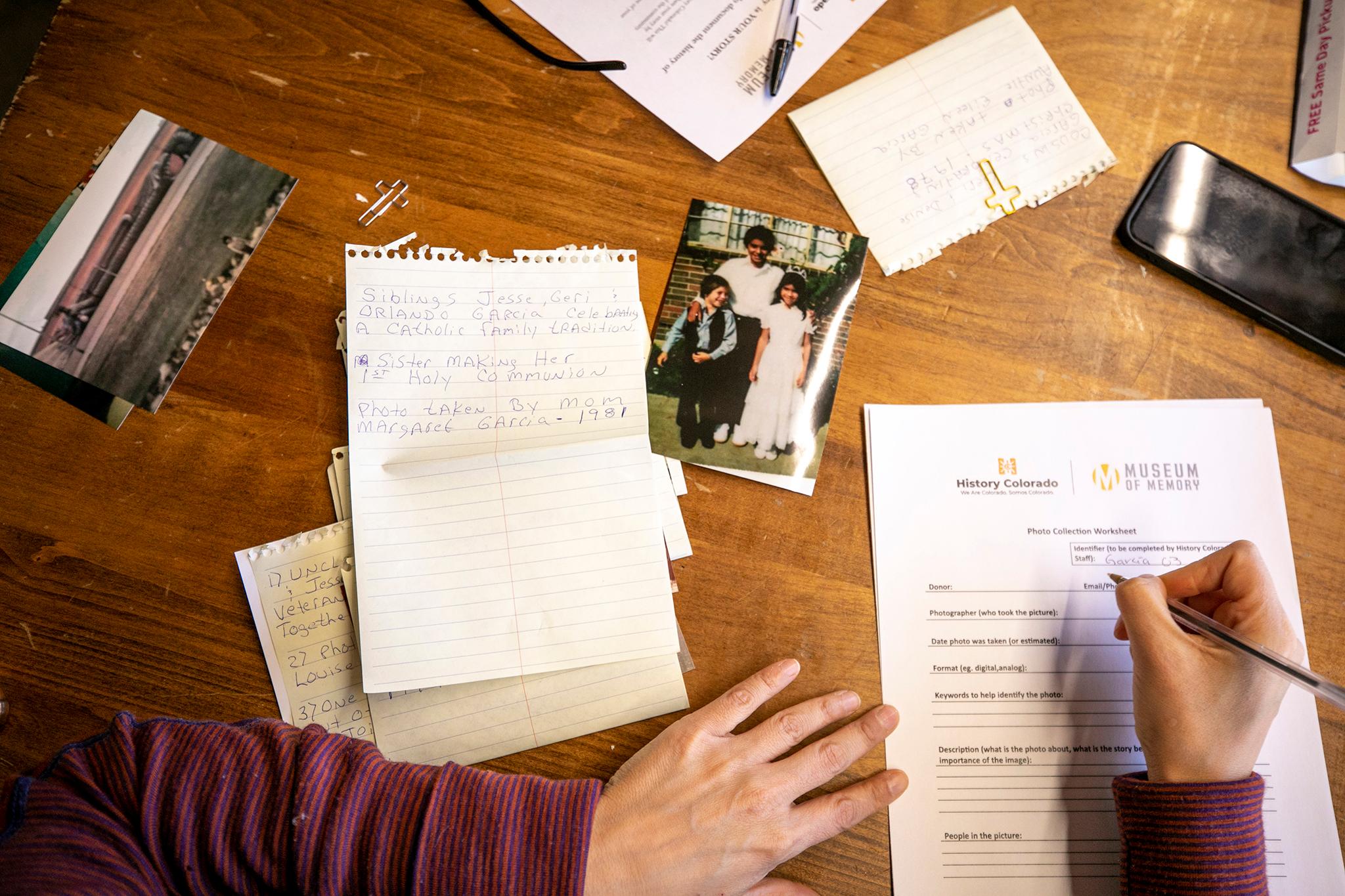

The story of what home means to these residents is why Garcia and about 20 others dug deep into their dressers and closets for old photos of their time in the neighborhood to bring to the History Colorado Sun Valley Neighborhood Memory project.

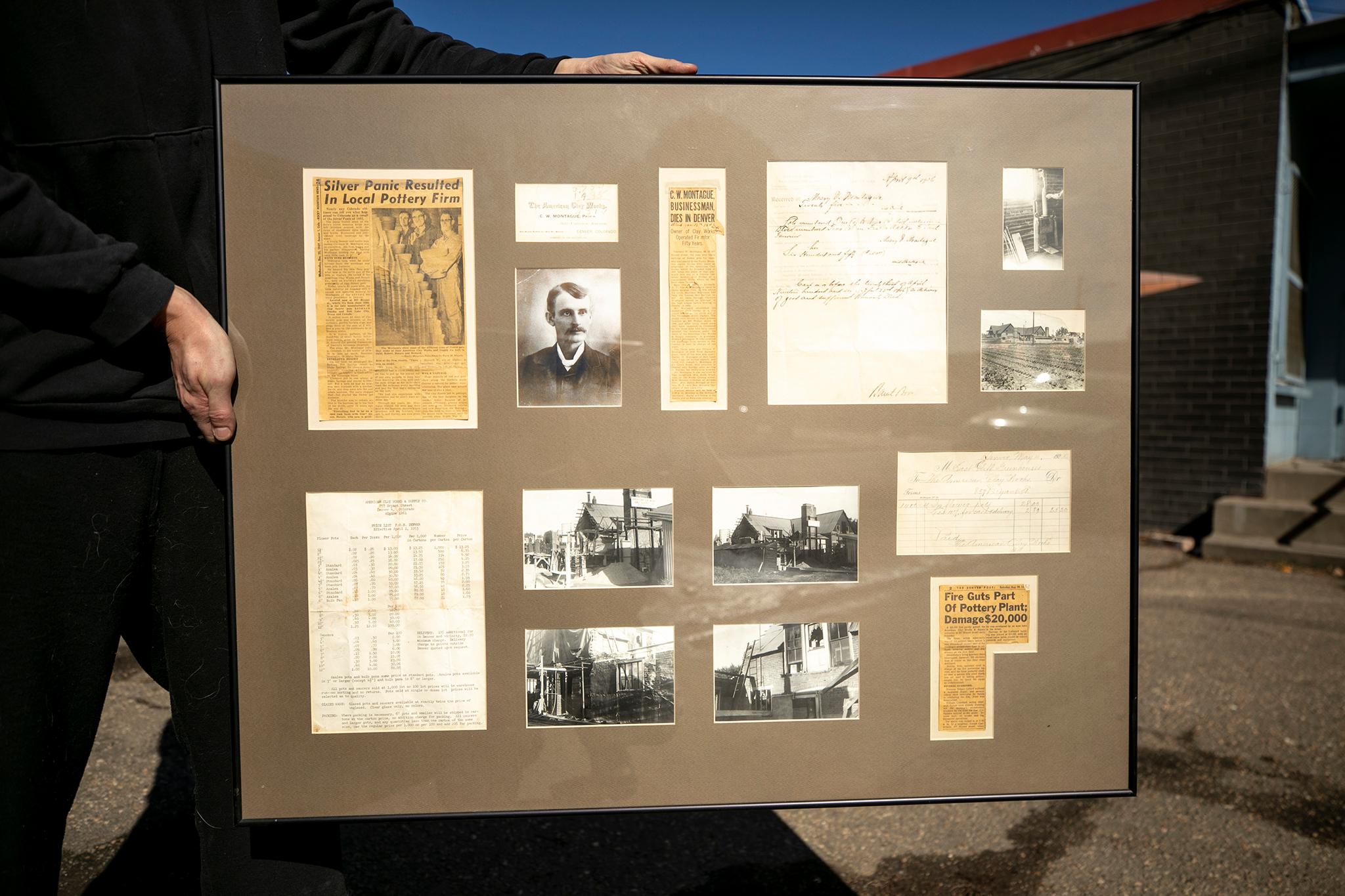

The project is a part of History Colorado's Museum of Memory Initiative, which focuses on curating history from underserved neighborhoods through photos and memories of the residents who either once lived there or currently live there.

The collection of photos and oral histories offers a way for neighbors to tell their own stories, which typically they don't get a chance to do.

"The ownership and the authorship of the stories and the history and the memory is the community's," said Maria Islas-Lopez, manager of the Museum of Memory initiative. "We are here to amplify the community's voices and we are here to recognize that community is the expert in their own history. These types of projects allow us to be here and say, how... can we actually honor the way that you want to represent your history and reclaim the history of the neighborhood?"

The Museum of Memory initiative has already begun collecting history from residents in Five Points, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, and several cities in Pueblo County. The initiative is currently working its way through Denver with projects on the Northside, Auraria and Sun Valley.

Islas-Lopez said preserving Sun Valley's history is more vital than ever.

Residents, of all kinds, would agree things are forced on Sun Valley residents as opposed to collective community changes. They'd add that the isolated neighborhood home to Empower Field at Mile High stadium, surrounded by industry and Interstate 25 was either never talked about or was considered the poorest neighborhood in Denver, a narrow view of one of Denver's most diverse neighborhood.

An area that once housed about 1,500 residents, Sun Valley is now home to detour signs, cranes, cracked cement and construction. The Denver Housing Authority is currently redeveloping the neighborhood. The agency tore down the public housing that was built in the '50s and is currently replacing them.

Once all is said and constructed, DHA would have created a mixed-income and use neighborhood.

It's a major upgrade from the old brick buildings but they are being built at the expense of displaced residents. DHA is bringing back residents, but the area is still in the building phase, leaving it feeling like a ghost town.

And so in comes the memory project to keep the area's history alive.

"[Through photo collecting and memory jogging] all of a sudden the story starts to be woven on its own," Islas-Lopez said. "The memories start to converge in beautiful ways and become collective memories. Through the communal experience we are not showing up as unique individuals. We're showing up as the Sun Valley residents across time."

Islas-Lopez said each of the projects work in similar ways.

History Colorado first reaches out to past, current and future residents to ask how can they preserve neighborhood history in a way that's authentic and doesn't feel like someone is parachuting in without fully absorbing and appreciating the stories.

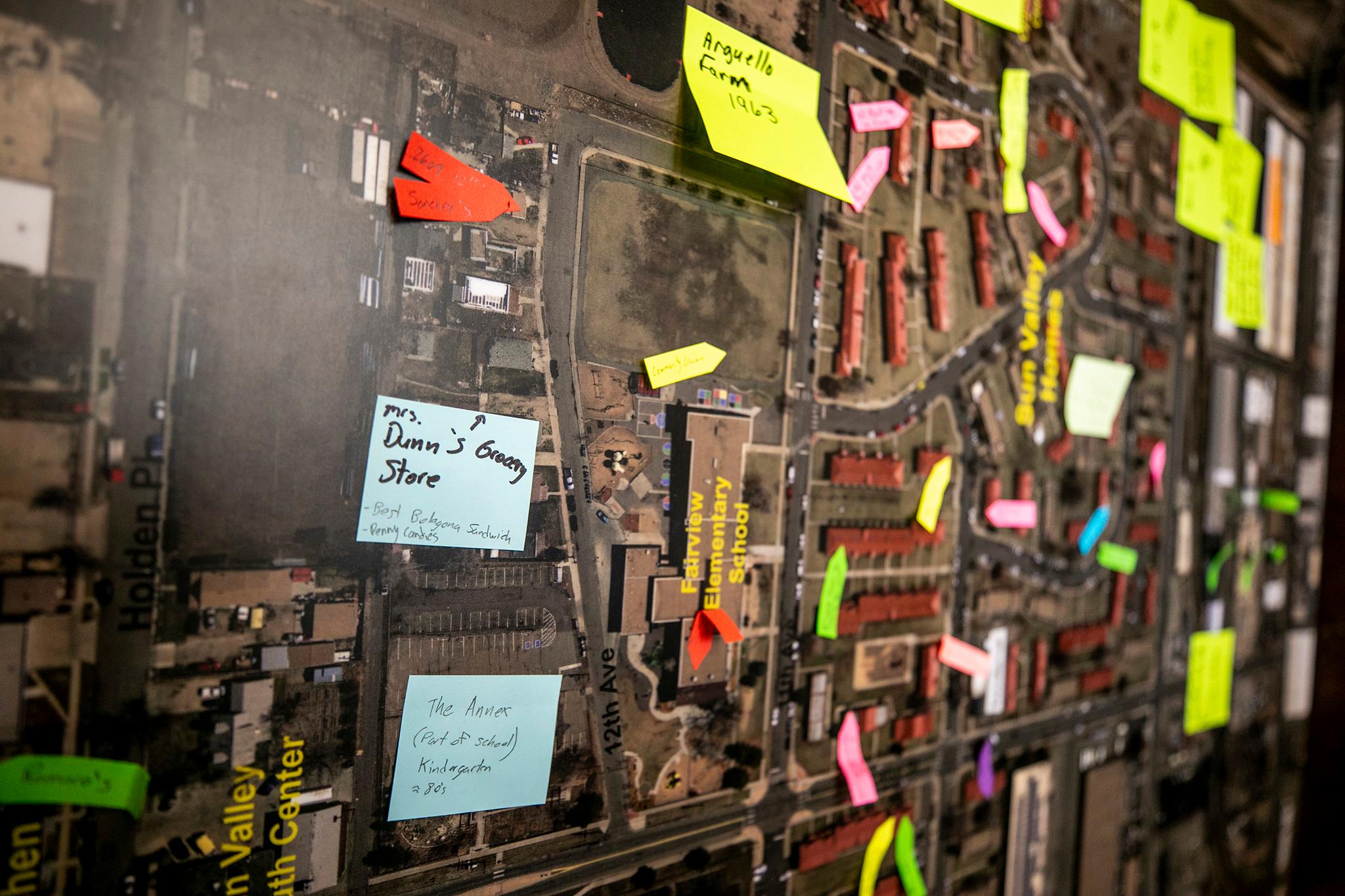

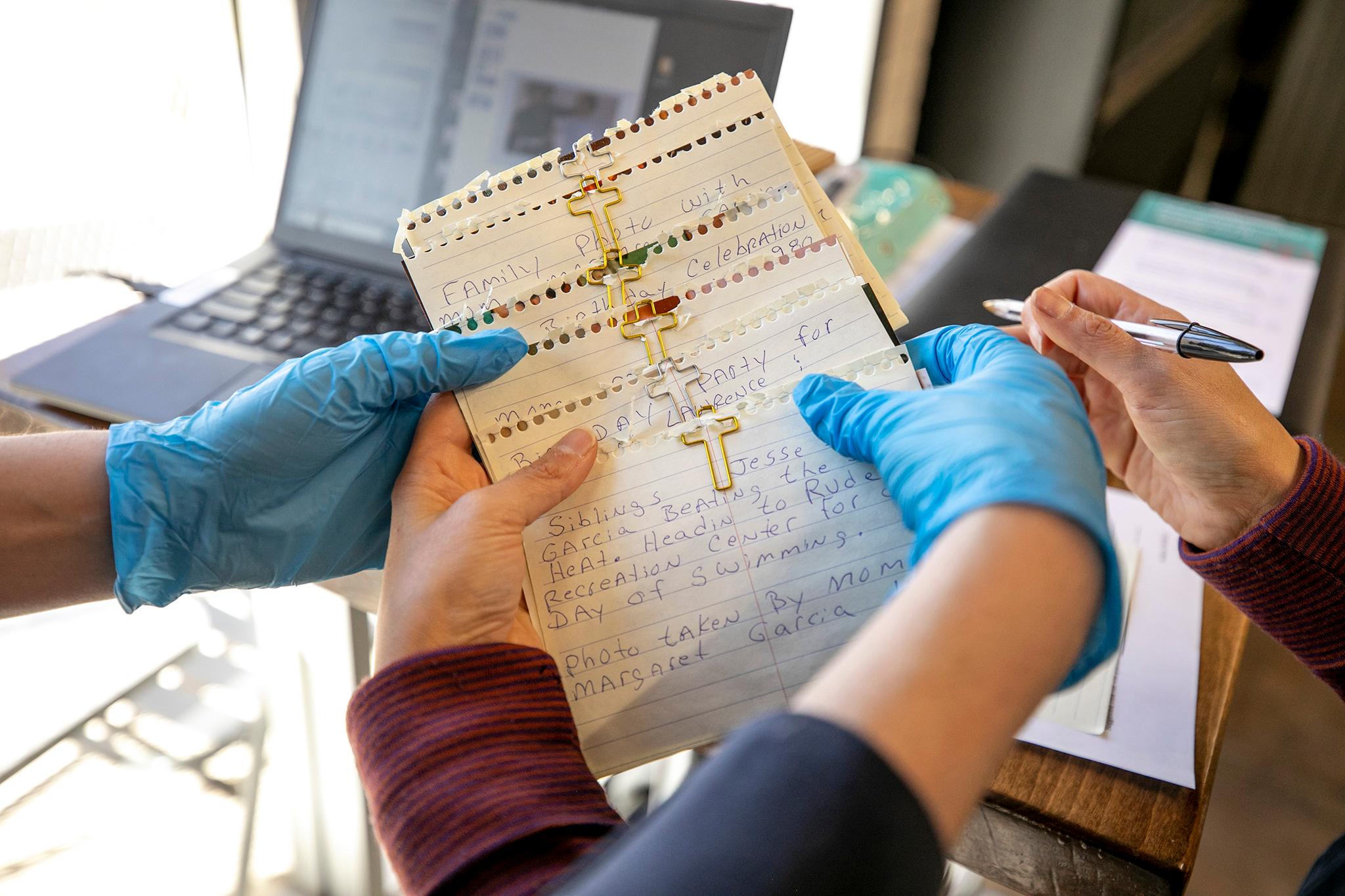

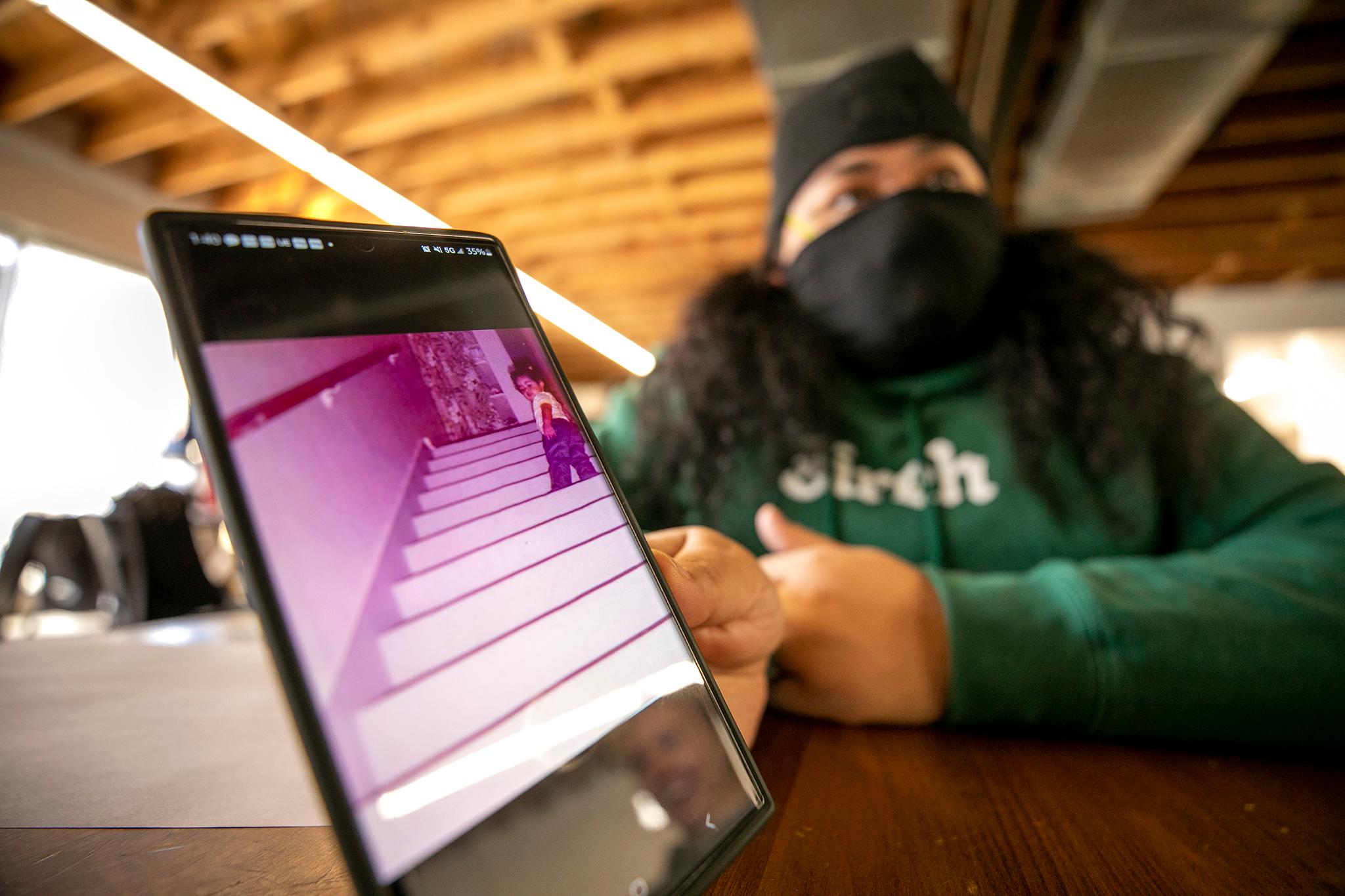

Then, History Colorado hosts community events centered around memory and storytelling. There are writing workshops where folks can write down stories and histories of events or just everyday life moments. They share with others who chime in, adding their own takes of a simple day or adding a new narrative of remembrance. Then there are also photo scanning events, like the one that took place in Sun Valley a few weeks ago, where people can brought in old photos and documents to be digitized. Staff members sit with residents to write down what's going on in the photo and why it's important. The photos are then scanned and returned.

"When you do a search of Sun Valley in our digital database at the museum, there are a handful of photos, meaning at the most five photos. And those are the only photos we have," Islas-Lopez said. "The archives do not document all the communities."

The photos collected during these meetings will be permanent fixtures in the archive, Islas-Lopez said. Like Garcia's photos.

Garcia grew up in Sun Valley public housing, living there until he graduated high school and joined the military.

"My grandma had six daughters and they all lived here," Garcia said.

As he looked through the photos with Islas-Lopez, he stopped at one and remembered the day. It was a picture of the mural "Urban Dope, Rural Hope" by Emanuel Martinez.

"The coolest thing about this photo is there was a day, it was a Saturday morning, where he invited us local kids to come and help him paint the mural," Garcia said.

Garcia recalled Martinez giving the kids a can of paint and telling them to paint four bricks at a time.

"He involved us, which is really meaningful because there was nothing for us kids to do," Garcia said. "That was a pretty neat experience. We all took part in painting this mural. It was a day. It wasn't the whole mural, but it was a day for the kids. You know what I mean?"

Listening to Garcia talk and stare at the photo is an immersive experience, which Islas-Lopez said is the point. Through storytelling, one starts to think about their own experiences and blend the two, Islas-Lopez said, which creates empathy and connection.

"It evokes memories, the feelings, the smells, the sounds, the noises that people heard that made this neighborhood, the neighborhood," Islas-Lopez said. "I'm so glad that you really felt that connection because that is the magic of storytelling. That is the magic of memory."

Garcia's home is gone. That mural is gone, too, whitewashed by the city in the '90s. Like other things in the neighborhood.

Garcia said looking around at the empty lots is bittersweet.

On one hand, he remembers growing up poor. The disinvestment leading to "dysfunction." On the other hand he sees the potential with the redevelopment. There's a chance kids in Sun Valley can get what he didn't get.

But the bittersweet part is Garcia wants those good changes for Sun Valley folks.

"We don't want gentrification, a bunch of rich folks from Chicago coming here who don't know anything about Sun Valley," Garcia said. "We want this neighborhood to be preserved. The preservation of the word at Sun Valley itself. We all wanted to get out...but there's hope that they will save the neighborhood while doing something better.

History Colorado can't stop gentrification, but it can preserve Garcia's memories and share those memories with others.

At the end of the project, the photos and recordings will be presented in the museum as interactive pieces. Voices of the residents will play in the museum, talking about how, although they were sequestered, they had each other. How they put their clothes out to dry on lines outside their homes together. How they walked to school together. How they played outside together. And how they had dreamed together of better lives.

Marisol Larez, another former resident, said projects like these are important specifically because of the community's involvement. She lived in the older DHA buildings like Garcia, but when those were knocked down, she didn't return.

She said looking around there are only a few people left and as development and life continues, no one will be around to tell those old stories and different narratives. But Larez said hopefully this project would change that.

"This is an opportunity to make sure that the history of this neighborhood is told by those of us who lived it," said Marisol Larez. "It makes sure that we're telling the story from the inside. This wasn't a forgotten neighborhood to us. We didn't look at it that way because this is all we knew. We love this neighborhood and where we grew up."