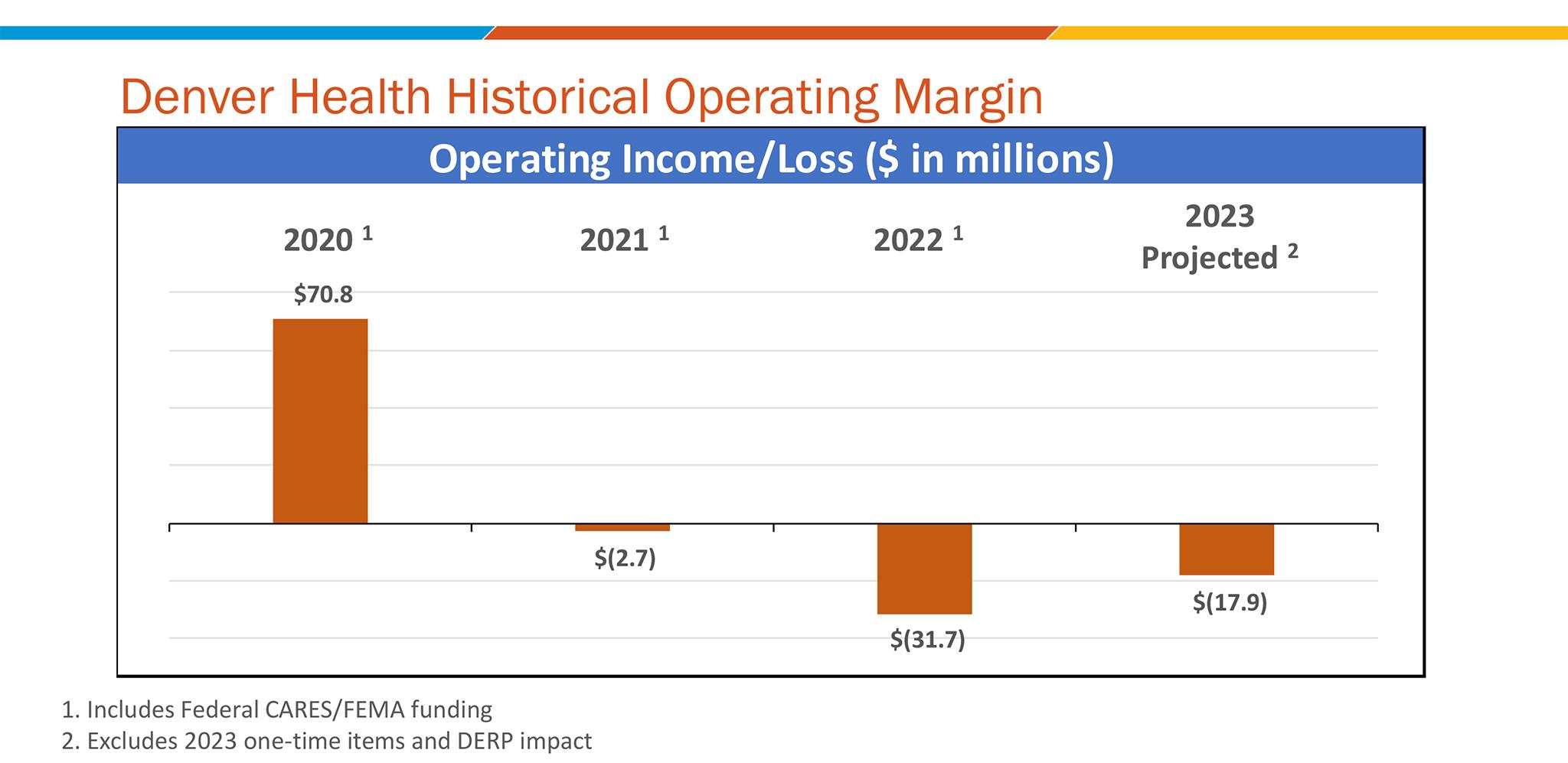

Denver Health ran a nearly $32 million deficit in 2022. This year, the hospital was projected to run a nearly $18 million deficit, but a few one-time grants mean the hospital could come close to breaking even, according to CEO Donna Lynne. The hospital has only run a deficit one other time since the 1990s, in 2016 when it switched its IT system.

Denver Health's financial outlook for 2024, though, is not looking great.

The non-profit, safety-net hospital treats everyone who walks through the doors, regardless of insurance status. Even during typical years, the hospital runs on tight margins, making maybe 1% or 2% profit that gets reinvested in the hospital, according to Lynne.

But with rising staffing costs and more uninsured patients seeking treatment, nothing has been typical since the pandemic began.

"We are at a critical point, I thought it was bad enough last year," Lynne told City Council during Wednesday's budget hearing. "You can't lose money year after year."

Part of Denver Health's money to cover for uncompensated care comes from the city, and a few months ago, Lynne requested that Denver increase its portion. But in Mayor Mike Johnston's 2024 budget, that figure stayed unchanged at about $30.8 million. In 2023, the hospital's overall cost to care for uninsured patients is nearly $136 million.

On Wednesday, Lynne again asked for more money. She made one thing clear: Denver Health's potential deficits are only set to grow, as the hospital faces systemic funding issues.

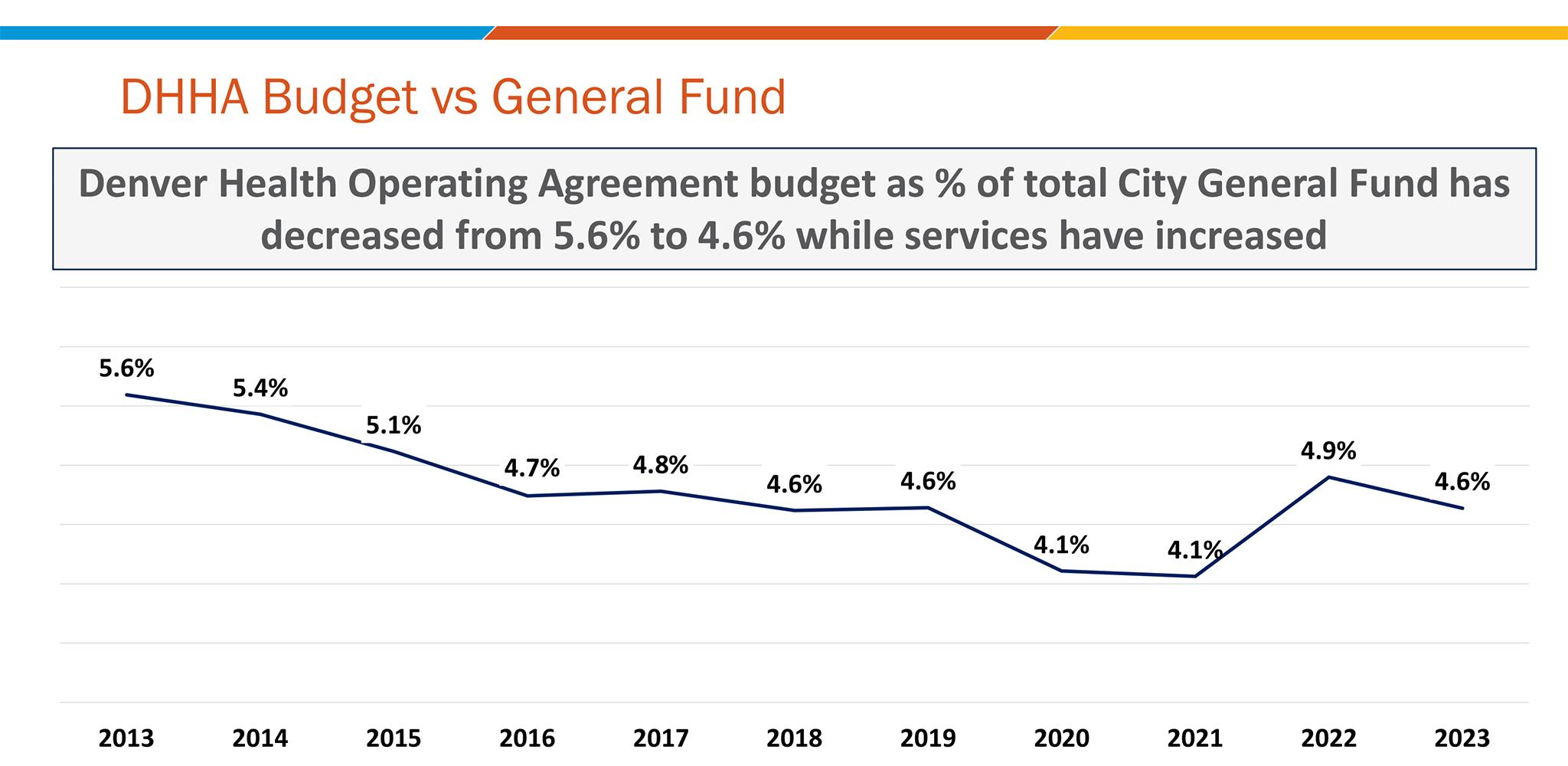

While patient costs have gone up, the city of Denver's contribution to Denver Health's budget has hardly changed since 2017.

In 2017, Denver's nearly $30.8 million in funding covered around 44% of the hospital's budget for uncompensated care. But with more uninsured patients and rising operational costs, that money now only covers around 23% of Denver Health's projected 2023 spending. Denver Health's proportion of the city budget has decreased as well; in 2013, the hospital received 5.6% of the city's general fund, while in 2023 it received 4.6% of the general fund.

"The idea that our reimbursement is flat, it's mind boggling to me," Lynne said.

This time around, Lynne asked Johnston for more money. But when the 2024 budget came out, the city's contribution to the hospital's uninsured costs--the major driver of Denver Health's deficit--stayed about the same. Overall costs the city pays Denver Health for other services went up about 6%.

"I was really disappointed. We got a written notification from the city about what the budget was," she said. "I quite frankly was stunned that it was communicated in the way that it was communicated and that it was, 'We can't deal with this right now.'"

Lynne said she knows the city cannot necessarily fill that entire gap, but she was hoping to see some recognition in the budget of the work Denver Health does and the hospital's increasing costs.

"I am a deep believer in Denver Health," Johnston said at the budget hearing Wednesday. "There is a major structural gap here in the funding structure, and we as a city are not going to fill a $100 million gap."

Johnston talked about other potential solutions, such as increasing the number of insured patients and pushing neighboring municipalities to designate some funding for Denver Health, which is the only safety net hospital in the state.

"In the short term, I will say we know how significant the challenges are," Johnston said.

The increased costs have come from the hospital's proportion of uninsured patients, which have skyrocketed since the pandemic.

Denver Health gets part of its funding through the federal government, from patients on Medicare and Medicaid. But the U.S. government only covers about 80% of those bills; the hospital covers the rest.

Another portion of the hospital's budget comes from patients with private insurance. But because Denver Health is a non-profit hospital, those patients only make up about 15% of the hospital's revenue. According to data from Denver Health, private insurance makes up at least 30% of revenue at private hospitals in Colorado.

A third group of patients are completely uninsured, meaning Denver Health takes on the full cost of their care. That's part of their mission, and why the balance book is often tricky, Lynne says. But recently, Denver Health's proportion of uninsured patients has gone up at much higher rates than other patients.

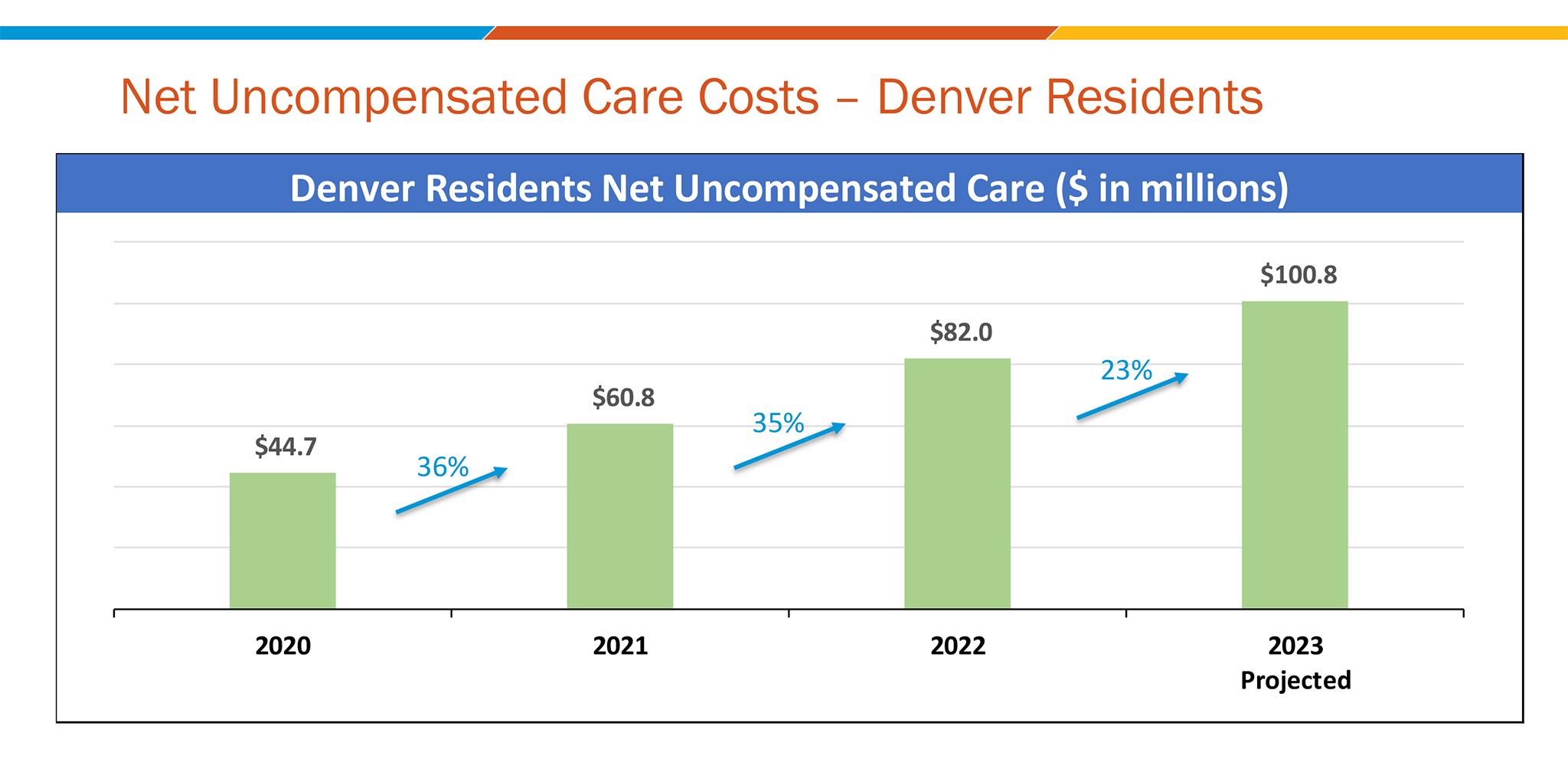

In 2020, uninsured patients cost Denver Health almost $45 million. In 2023, that figure is projected to come in at $100.8 million.

"Since COVID, people are coming to Denver Health in greater numbers, and our costs have gone up much more," Lynne said. "The amount of uncompensated care that we have since 2020 has actually more than doubled."

Lynne said the city's growing homelessness crisis is driving some of these costs.

Denver's homeless population has increased in recent years. A 2023 Point-In-Time count found that the number of people living on the streets in Denver and its surrounding counties increased by almost 32% - a figure some experts consider to be an underestimate. The figure does not take into account people living in shelters.

"It doesn't take a lot to know, as you walk around the city, you're seeing more and more people on the streets, and more and more people who really need care and probably are not getting care, so they tend to come to Denver Health," Lynne said.

Lynne said Denver Health has also seen an increase in uninsured patients as nearly 19,000 migrants arrived in the city during the past year.

Denver Health has also started paying for apartments for a portion of homeless patients who are recovering from medical care, further driving up costs. Lynne said these patients would likely end up on the street and then back with an infection similar issue, so the hospital tries to house people in the short term. Denver Health does not get any extra funding for these apartments.

Lynne emphasized that serving all these patients is part of Denver Health's mission, but the increase in uninsured patients has outpaced sources of revenue.

"If we weren't here, those patients, they're going to get sicker, and they're going to land up at other hospitals' doorsteps, and quite frankly, they are not welcome," Lynne said. "They are welcome here at Denver Health."

Meanwhile, labor costs have gone up, and one-time cash infusions from the pandemic are drying up.

As scores of healthcare workers resigned during the pandemic, the cost of labor in the healthcare industry went up. Lynne said Denver Health has sometimes had to pay for travel nurses to fill gaps, which cost a lot more than full-time staff.

Like the City of Denver, Denver Health received federal pandemic recovery money from the federal government. But with the federal health emergency officially over, and as the hospital spends that money, that funding will soon be gone.

Lynne said the hospital has received philanthropic support in the past, and is working to increase its fundraising efforts with potential donors, but that one-time cash is unreliable, and often allocated toward specific programs, not overall operating costs. The hospital got $10 million from Kaiser and $5 million from the state this past spring, to help with the 2023 deficit.

Plus, during the pandemic, millions of people nationwide were able to gain access to Medicaid. But when the emergency ended this year, people started losing Medicaid insurance, including up to 325,000 people in Colorado. For Denver Health, that means patients whose coverage would previously have been reimbursed by the government at about 80%, are now completely uninsured.

Because of the funding issues, Lynne said the hospital often needs to decrease the amount of patients the hospital can serve.

One of the programs that has faced restrictions is psychiatric care, even as need continues to grow.

"We have 78 psych and substance abuse beds," Lynne said. "We pretty much can only open 50 or 55 of them at any time based on staffing. So if the staff costs too much, we don't open the beds. I would love to have all of our beds open."

Another way Denver Health has tightened its budget has been by giving salary increases that are below market rate -- something that makes staff retention even harder, when nearby hospitals can provide higher rates. Lynne pointed out that the city of Denver budgets for regular salary increases for city employees based on the market; something Denver Health cannot afford to do, despite receiving city funding.

As Johnston focuses on getting people off the streets, Lynne expects the hospital to see more uninsured patients.

Johnston's new pallet shelters, for example, will have wraparound services with the goal of connecting people previously living in encampments with medical and psychiatric care. Lynne said that when people secure more stable housing, they often increase visits to Denver Health, since they have the stability to address longer term issues like dental care.

"The supportive services for, whether it's the tiny homes or it's the motels, are trying to make sure those individuals stay in their housing," Lynne said. "They're going to need more than just the key to an apartment or building, they're going to need to treat some of the underlying conditions that have perhaps led them to be living in a tent on Eighth [Ave.] and Logan [St.], for example. Guess what? Eighth and Logan is pretty close to Denver Health."

While some of these underlying challenges with homelessness, migration and the aftereffects of the pandemic are playing out nationwide, Lynne said Denver Health's financial problems are unique. That's because many states have designated tax funding for their non-profit hospitals. But Denver Health only gets money from the city, as decided by the Mayor, and from city jails for their healthcare services.

"Many of them have other kinds of support, either from their state, from their city or from the taxpayers themselves... even in some conservative states," Lynne said. "There's an understanding that you can't not support your safety net."

Editor's note: This article was updated to include information about overall city costs paid to Denver Health.