This article is a part of Denverite's Street Week: Tennyson series. We're exploring the area by way of the history, people, carp-filled lakes and weird houses that define it. Read more Tennyson stories here.

It can be hard to follow Tennyson Street through Denver's southern reaches. Gaps in the corridor grow as it is interrupted by Sloan's Lake, then Morrison Road, then Harvey Park Lake. But if you arrive at a short segment further south, near its intersection with Iliff Avenue, you'll find a piece of the city's prehistory tucked away behind a gate.

Surrounded by '50s era homes, there's a French "manor house" that's existed in some form since the 1920s, owned by major figures of their days before the neighborhood grew up around it. The sprawling property was still part of Arapahoe County when its original two-story farmhouse was built. Its lands would become Harvey Park, named for the man who finally sold off its rolling acres to a developer.

We visited the home to learn more.

In the early days, 2277 S. Tennyson St. was about as far outside of Denver as you could get.

Mike Allison grew up in this house, decorated today with '60s and '70s-era flare: colorful wallpaper and carpets that climb up the sides of a bathtub and into its two kitchens. Today, it feels like an "urban oasis," he said during a recent tour of its grounds.

"It is," Diane, his wife, added. "You'll feel it once you walk in. The rest of the world sort of melts away."

The couple have lots of fond memories here, but they've also become students of the home's deeper history, back before it became an oasis. During our visit, Mike pulled an old framed photo out of a closet, showing a time when the property had no neighbors in sight.

The original home here was built in the 1924, when Bandleader Paul Whiteman bought the 320-acre property for his parents. The Denver Post's 1976 obituary of Whiteman describes his purchase "mostly as a ruse" to get his father, Wilberforce Whiteman, to retire from his position as "supervisor for music" for Denver Public Schools.

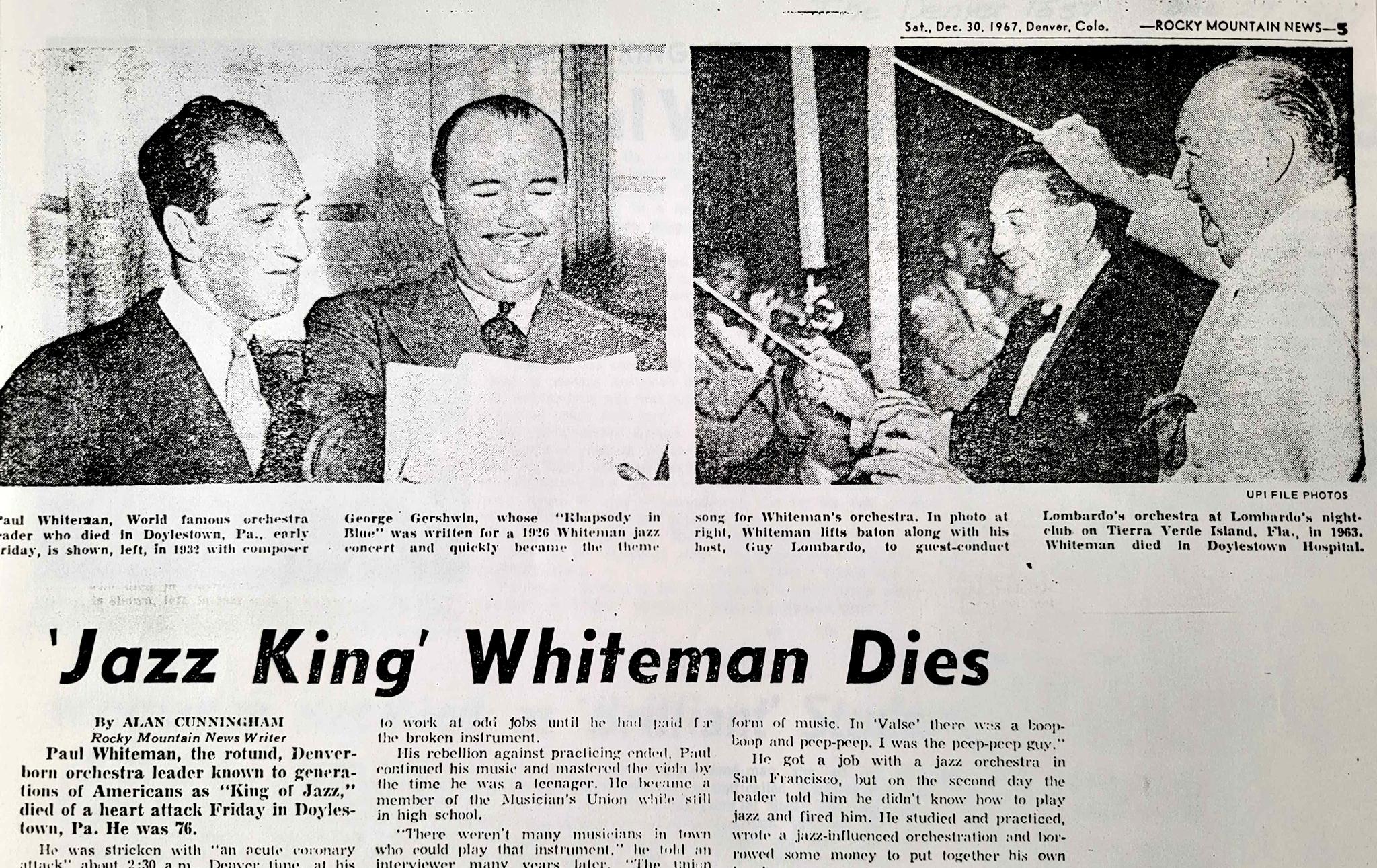

The younger Whiteman, who was born in Denver, could afford the parcel because he'd become a celebrity, "rising to the heights of international popularity," according to one newspaper article from 1963. His obit in the Rocky Mountain News states "he was widely given credit for bringing the jazz idiom out of the back room, and endowing it with concert-hall respectability."

He called his contribution to the genre "symphonic jazz," eschewing improvisation for written arrangements. "Rhapsody in Blue" was one of Whiteman's most famous orchestrations, a work that City Council member Kevin Flynn said he commissioned from George Gershwin the same year he bought the Arapahoe County ranch land. The bandleader would help kickstart the careers of other famous names of his era, like Bing Crosby, who called him a "giant in the music industry." But he'd become more controversial over time, as music historians began to examine how this white musician "sanitized" a genre rooted in Black culture for white audiences and succeeded where many of his contemporaries of color did not.

Whiteman's parents lived out their last days in the Tennyson house, apparently sharing the land with some Siamese cats, "personally presented to Paul Whiteman by the king of Siam" as he traveled the world on tour. According to one old article, Whiteman gave the cats their own buildings to live in.

The Whiteman family sold the property in 1936, as it transformed into a French estate.

It was purchased by Henri de Compienge, a "representative of French oil interests" who came west before World War I to develop oil fields in Wyoming, according to his short 1971 obituary in the Denver Post.

According to the Allisons, de Compienge brought "artisans" from Europe to Denver, to help him significantly transform the Whitemans' old farmhouse. They added on new wings, separating"public" entertainment spaces from "private" servants' areas and shipped materials into town from all over the world. One marble mantle, Mike said, came straight from a French chateau. Another is accompanied by a framed document, showing its stone was hewn in Italy.

De Compienge's crews endowed the house with high-tech flourishes of their day, big, expensive windows and seamless tubes of glass - a feat of engineering - for its chandeliers.

"It was a big, big project," Diane told us.

In its heyday, those big glass windows would have given pristine views of the mountains, rising over rolling green hills and Riviera Lake, which still exists in the neighborhood.

In the '40s, Diane said, de Compienge sold his masterpiece to Frederick W. Bonfils, nephew to Denver Post founder Frederick G. Bonfils, who sold the land again in 1948.

Arthur Harvey entered the picture, changing the property forever.

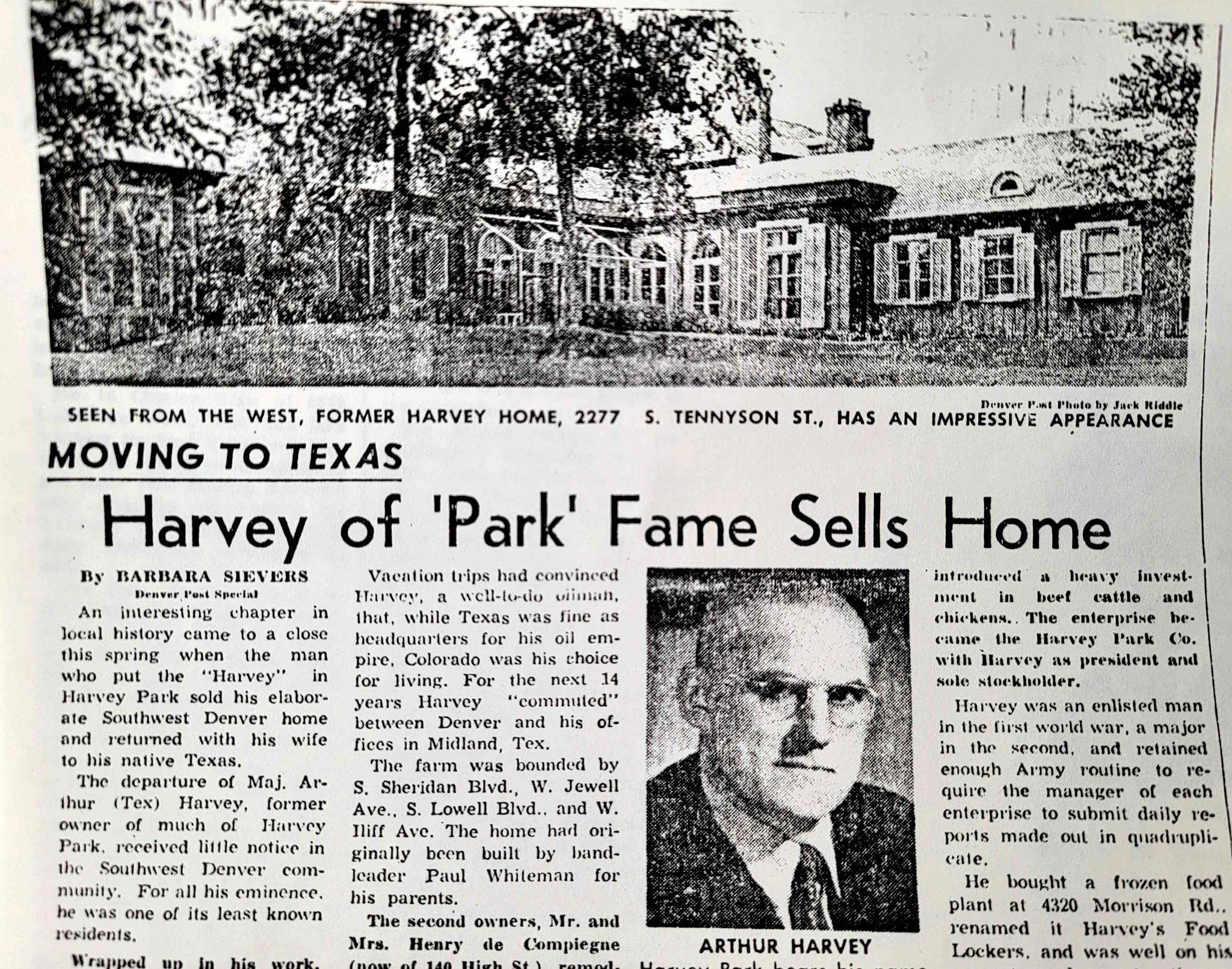

Harvey was an oilman who, according to one 1962 newspaper story, preferred living in Colorado despite having to commute regularly back to Texas for work. Articles about Harvey, including his obituaries, say he rose to control vast capital without any formal education, teaching himself everything there was to know about drilling and selling oil once he got hooked on the business.

After he bought de Compienge's mansion, Harvey purchased more land around the property. He installed "an elaborate underground irrigation system" on his 480 acres, where he raised beef cattle and chickens. He'd also dip his toe into other Denver markets, purchasing a "food locker" facility on Morrison Road (where a new rec center is currently slated for construction). He didn't hang onto his irrigated acres for long.

"Harvey later sold the land to Aksel Nielsen, Denver contractor and builder, who turned the farmland into the approximately 4,500 homes," says his 1967 obituary in the Herald Dispatch, which called itself "the only newspaper in the world that gives a darn about Southwest Denver."

Their article added that the neighborhood became known as "Harvey Park" simply because that was what officials called the area on annexation documents, as Denver sought to slurp up more and more land from surrounding counties. The city wouldn't create formal statistical neighborhoods until the 1970s.

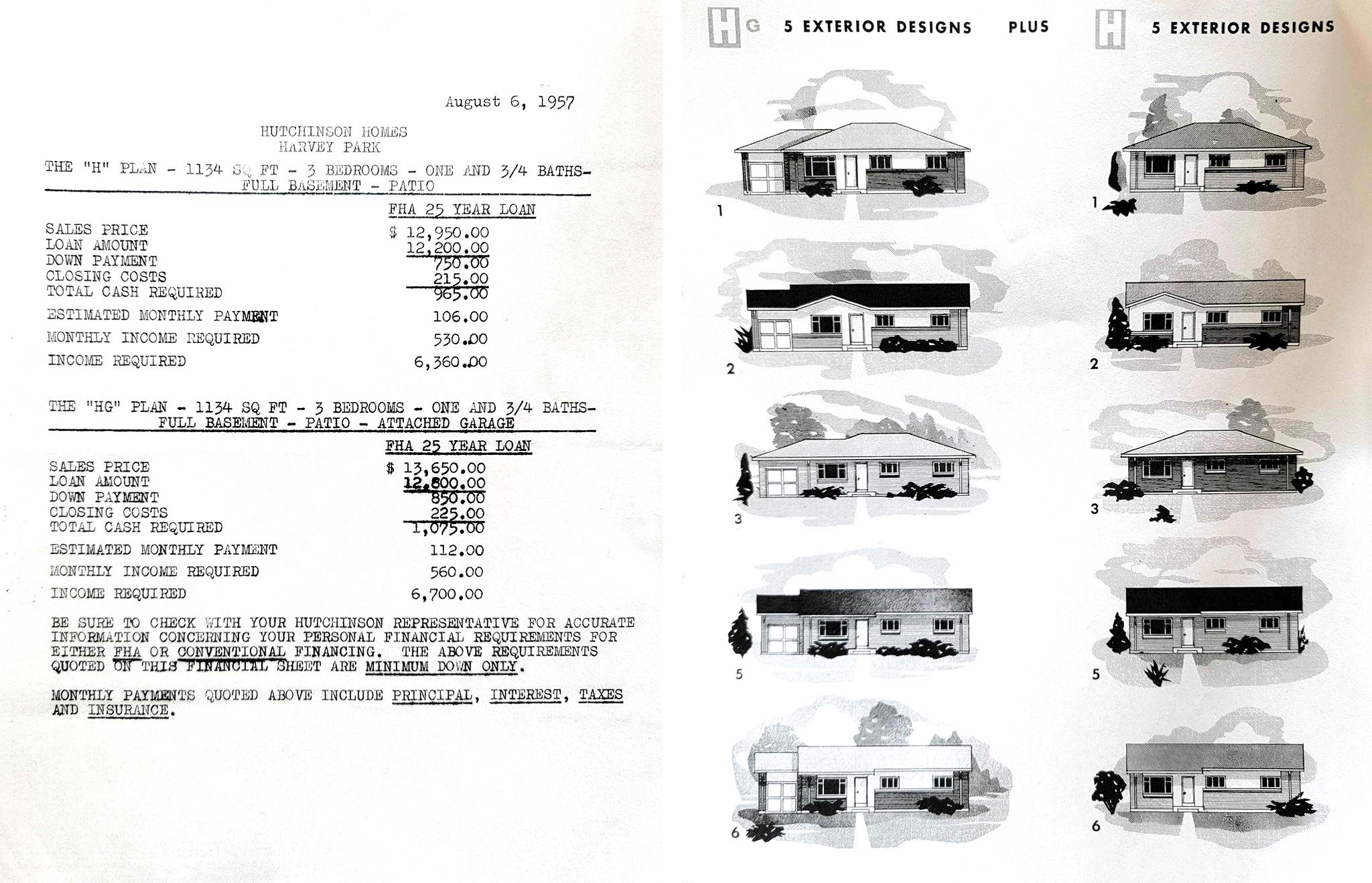

The land surrounding the French manor house became attainable housing, part of a building boom to accommodate soldiers coming home from World War II with plenty of cash in hand. Advertisements from the era boasted three bathrooms, "brick veneer" and full basements. You could buy their more expensive "HG" models - they had attached garages - for $13,650 outright. If you had just $1,000 cash, you could get on a mortgage for $112 a month.

Harvey sold his home, now on a much smaller parcel, to Mike Allison's parents in 1962.

His departure "received little notice in the Southwest Denver community," a Denver Post story said at the time. "For all his eminence, he was one of its least known residents. Wrapped up in his work, the man had lived quietly and unobtrusively on his two-acre estate at 2277 S. Tennyson St. He seldom entertained, spent much time out of town, and took virtually no part in civic and community affairs."

The home and neighborhood have changed more slowly since then, but more shifts are on the way.

Mike Allison's parents put their own touches on the property, redecorating and adding an indoor pool off of their master bedroom suite. It was a home for entertaining, Diane told us, and her in-laws put that capacity to use as often as they could.

The neighborhood is quiet now, but Mike remembered it was full of life and adventure when he was young.

"The neighborhood was different because there was a lot of kids. It was the baby boom thing. I was at the tail end of it, but I had older siblings and all the houses around here had four or five kids," he told us, adding his friends were always enamored with the property.

Like the home's previous owners, his father, J. W. "Bill" Allison, was a local bigwig in his own right. Like Harvey, he was born in a humble home, served in the military and built his own fortune in the oil business. In his later years, he served on the boards of the Denver YMCA and Colorado Academy. He received an obituary in the Intermountain Jewish News after he died, Mike said, a rare honor for a gentile.

Mike said his father probably saw the property as a sign of how far he'd come, from Depression-era Louisiana to this grand manor.

"This was his pride and joy," he said.

The house has lost its shine over the years, but Mike, Diane and their family are currently working to make repairs and spiff the place up. They're planning to list the home for sale this spring, and they're hoping whoever buys it decides to keep its architectural - and cultural - legacy intact.

While they're set on selling, both Mike and Diane said they'll be sad to see the place enter new ownership. Diane said she tears up, now and then, when she thinks about it.

"This is a unicorn," she said.

Read all the stories from Street Week: Tennyson here. (And dip into the Street Week archives with 2021's Morrison Road and 2020's Bruce Randolph.)