A few weeks ago Genesis Daniel Perez, a mother from Venezuela, was sleeping in a tent with her children and parents outside a city-run motel. They'd timed out of the shelter as temperatures dropped. Then, she told us, her father was hospitalized when he was exposed to the cold.

In the last year, the city has sheltered over 30,000 people who've recently crossed the border and found their way here. Their arrivals represent a sea of humanitarian need that's pushed local resources to their limits, for the city, Denver's school system and for medical providers.

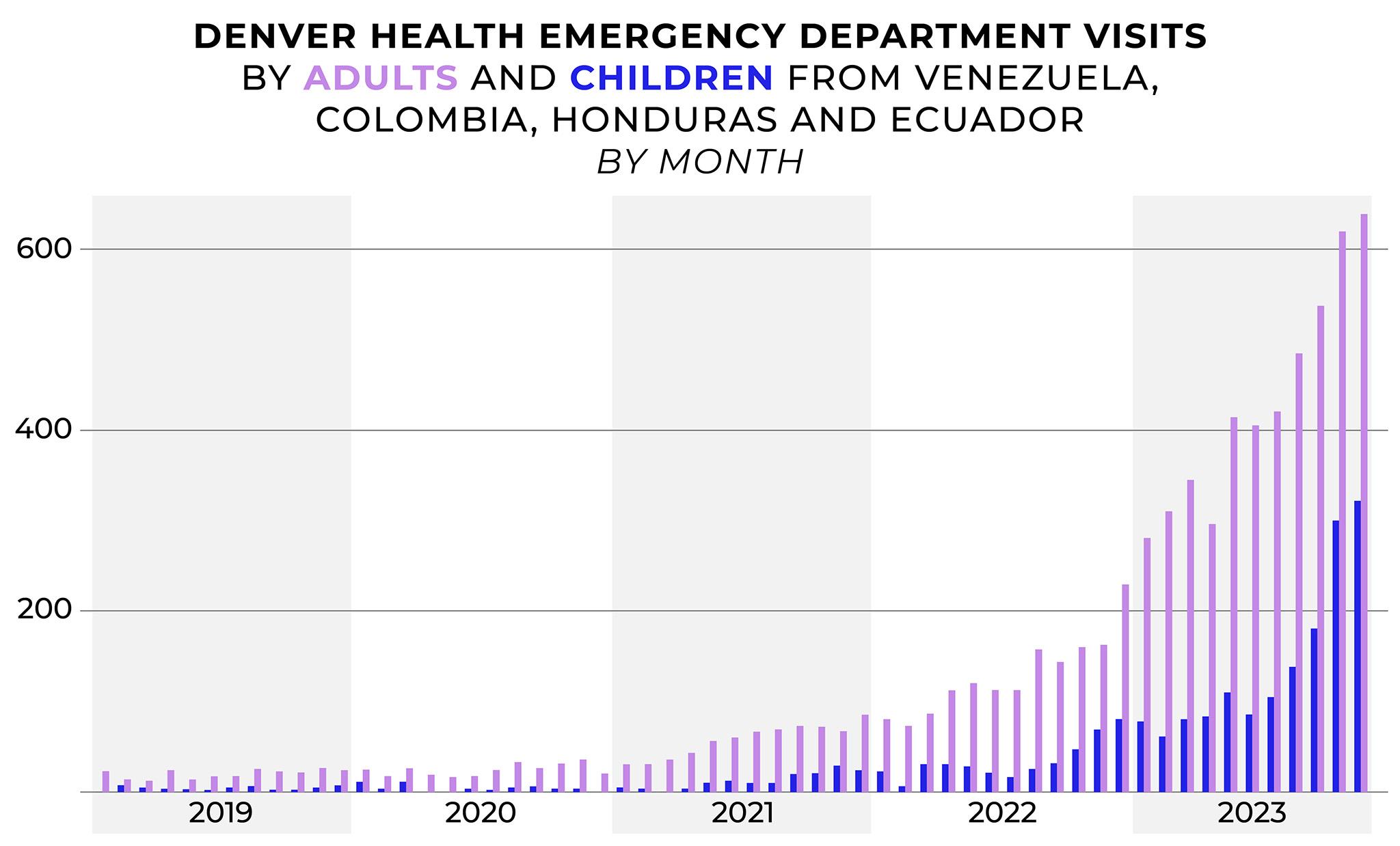

Data provided to Denverite from Denver Health show close to a 6,000% increase in ER visits by children from Venezuela, Colombia, Honduras and Ecuador between 2020 and last month - from about 5 kids each month to over 300 in November. Visits made by adults from these countries have also risen significantly.

Jon Ewing, a spokesperson with the mayor's office, told us the city stopped booting families with kids out of their hotels on Nov. 17, and they've invited many back into shelter. Perez told us she did get a roof over her head. But even those inside need care, and there are still many hunkered down in tents who will continue to risk their health as winter begins in earnest.

Doctors are doing their best to help, but they can only do so much.

Denver made it through summer with relatively few arrivals from the southern border, but numbers climbed significantly in October. Dr. Taylor McCormick, director of Denver Health's pediatric emergency and urgent care departments, said that timing has been particularly difficult on the hospital.

"Every year, we have a big peak when respiratory illnesses - RSV, flu and COVID - hit their max, and we are nearing that. So that's the context where we're seeing record numbers in our ER," she told us. "On top of that, we have this new surge of patients, that we are absolutely happy to take care of. We want to take care of everybody who walks in the front door and we want to do our best to take care of them."

Not everyone counted in Denver Health's numbers are asylum-seekers, McCormick cautioned. Hospital workers don't ask about immigration status, but they do ask patients about their countries of origin. Looking back to 2019 provides a baseline, she said, which helps illustrate how migrant arrivals have impacted the ER.

On the job, McCormick has seen patients who picked up infections and traumas on their long, dangerous journeys to the U.S., patients who caught illnesses inside the city's motels and others who got sick as they languished in sidewalk encampments.

"We're ruling out tuberculosis. We're seeing a ton of chickenpox kind of rashes. We're seeing lots of diarrheal illness, abdominal pain, and then just regular stuff, like kids that have RSV and bronchiolitis and fevers. Kids that are dehydrated, malnourished need to be admitted to the hospital for IV fluids or oxygen support," she said. "So it's really the gamut of all of it."

Dealing with all these people is stressful, McCormick said, but added ER doctors are "used to being stretched" and can handle it. What's tougher is the reality that many of these patients have nothing else to fall back on. While some return to shelters when they leave, others exit back to city streets. And the emergency room is often the only path they have to access care.

"They are coming in and they have no pediatrician, they have nowhere to go after they see us," she said. "It's always really hard to send somebody back out onto the street."

All this care also represents financial trouble for medical providers.

Migrant families visiting ER usually have no insurance, and also cannot pay out-of-pocket for their care. Denver Health is a "safety net" hospital, meaning it's set up to serve people in this situation in normal times.

But Dr. Steven Federico, a pediatrician who serves as Denver Health's chief government and community affairs officer, said this moment does represent fiscal risk. The hospital has been racking up costs for uncompensated care long before migrants arrived in their departments.

"This is an outlier. It's an outlier at a time of great instability, on the heels of COVID. Safety net hospitals are really under duress. Costs have skyrocketed. Reimbursements are flatlined," he told us. "That population, landing in the emergency department with either significant health needs and no payer source, that strains the health system the most."

Federico added his colleagues estimate that migrant patients made up ten percent of all ER visits in October, which is "not an insignificant impact" to the financial picture.

Cathy Alderman, spokesperson for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, said her organization estimates as many as half of new patients at their Stout Street clinic are also new arrivals.

"That's something that we were expecting at Stout Street Health Center, and I think it's a real concern," she said, "because neither Denver Health or CCH wants to turn people away. But when people don't have Medicaid coverage, and we don't have other funding sources we can tap into, it means we're doing this work for free."

While ER visits represent the highest costs in this system, Federico said, patients also need to tap into emergency funds for other service providers, like pharmacies, to make sure they don't get sicker. Federico brought up a three-year-old he recently treated for pathogens he probably got from drinking dirty water on his journey.

"We've got to figure out how to pay for medicines that little guy needs before he gets sicker and ends up in the hospital and gets even more costly," he said. "So it builds. The problems build on themselves, both clinically as well as fiscally."

His emergency room has become another place in Denver where people are working to keep a handle on this crisis, as more people arrive every day.

"It makes me proud to live in Denver, to know that we want to do our best to help others," Federico said. "I thing we're having a hard time doing it, but I think we're stepping up in the ways that we can."