Narrow-neck lab beakers, work gloves cast in transparent resin squares and an assortment of metal baby dolls litter rusty aluminum shelves inside of a RiNo industrial warehouse. The ceiling leaks and cold rainwater puddles as Lawrence Argent’s loved ones carefully arrange the belongings of one of Denver’s beloved sculptors.

“He was kind of a master of materials, the way he designed things,” said Anne Argent, ex-wife of Lawrence Argent.

Argent is most known for the blue bear sculpture titled "I See What You Mean" that peers into Denver’s Convention Center. The renowned artist passed away in October 2017 of cardiac arrest at the age of 60, a shock to the community that was beginning to witness his ascension within the art world.

Seven years after his passing, the sculptor’s studio belongings will be up for sale to the public, giving Denverites a glimpse into the mad scientist’s creative phases and obsessions.

Here’s what you need to know about Argent’s estate sale.

Two storage units worth of Argent’s works will be up for sale beginning this Friday, May 3 at the Denver Rock Drill/Porto Power complex at 1717 E. 39th Ave., in the north end of the Cole neighborhood. Items will be priced from $5 to $10,000, much of it hasn’t been seen for 7 years.

Scheduled times to purchase:

Friday, May 3, 4-7 p.m.

Saturday, May 4, 10-4 p.m.

Sunday, May 5, 10-4 p.m.

Friday, May 10, 4-7 p.m.

Saturday, May 11, 10-4 p.m.

Contents for sale include finished and unfinished sculptures, parts, pieces, tools, maquettes, paintings, drawings, photographs and a handful of miniature blue and pink bears.

Unearthed storage belongings are a display of the artist’s many interests over the years.

Often drawn by the “absurdity of the material,” Argent drew inspiration from the world around him.

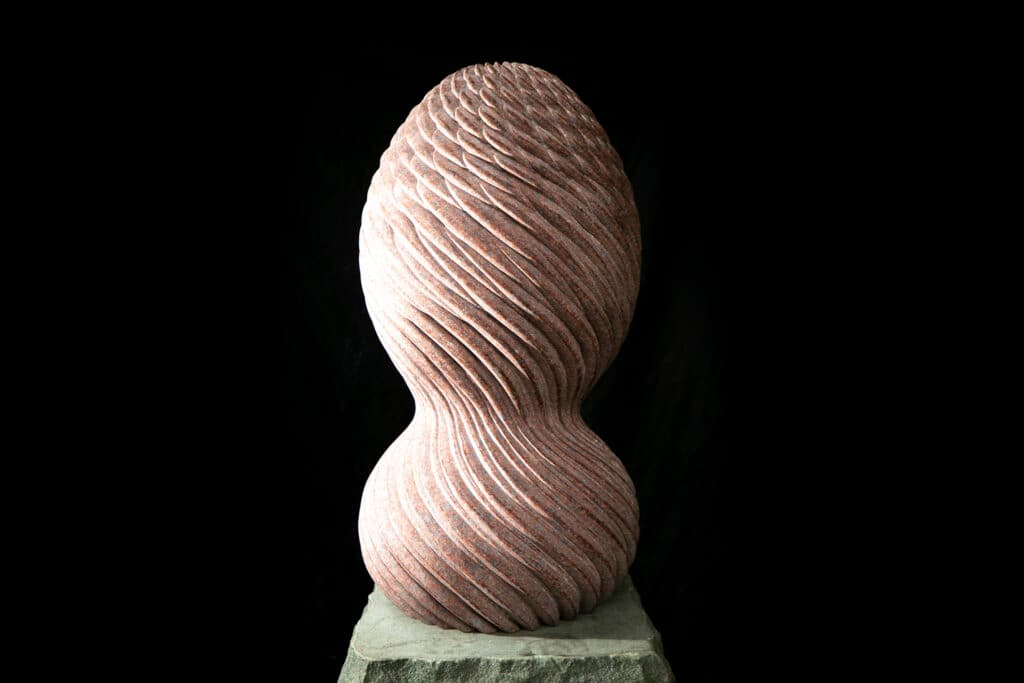

Hanging overhead are two large blood-red street sweepers that resemble oval shaped eggs. A 1999 piece titled "Cojones," Anne said Argent developed tendonitis for a year after time spent hand-cutting bristles.

A self-taught engineer of sorts, Argent created a mechanical one-way cage trap and an exercise bike that “exercises itself” with lead wings meant to draw attention to the irony and absurdity of heavy feathers.

Numerous spiral metal towers were made to resemble the Tower of Babel, inspired after completing an internship with plumbing manufacturer Kohler and metal light bulbs that are heavy enough to require good squatting form to lift.

Argent was also inspired by his two sons. A pacifier sculpture and photography were inspired by his son, Camron, “because [he] just always had to have a pacifier in his mouth,” Anne said.

Even the famous blue bear and a 3D printed train were inspired by the boys’ toys.

“At that time in the newspapers there were a lot of bears coming into people’s homes and raiding.” Anne said, recalling the brainstorming process for "I See What You Mean." “So we thought instead of us driving up to the mountains to go see the wildlife, what if the wildlife came down to check out what was going on inside of the Convention Center?”

The digital rendering of one of the boy’s toys lead to what we now know as Denver’s notable public art sculptures.

“I feel like I’m getting even closer to him even though he is not even here,” said Camron, Argent’s son.

The family first opened up the dusty storage units of Argent’s work almost four months ago, inventorying a pile of stuff that hadn’t been touched since Argent’s passing.

Some items in the sale used to hang in their home and others Camron, Argent’s son, had never seen before. Having a famous dad was a bit embarrassing growing up, but after pulling out these relics and reading a plethora of articles about his father’s influence, Camron hopes others can come to appreciate his dad’s hustle.

“I didn’t really realize the magnitude that he was at and how difficult it is to be successful as an artist,” Camron said. “He was reaching one of the highest points you can be as an artist.”

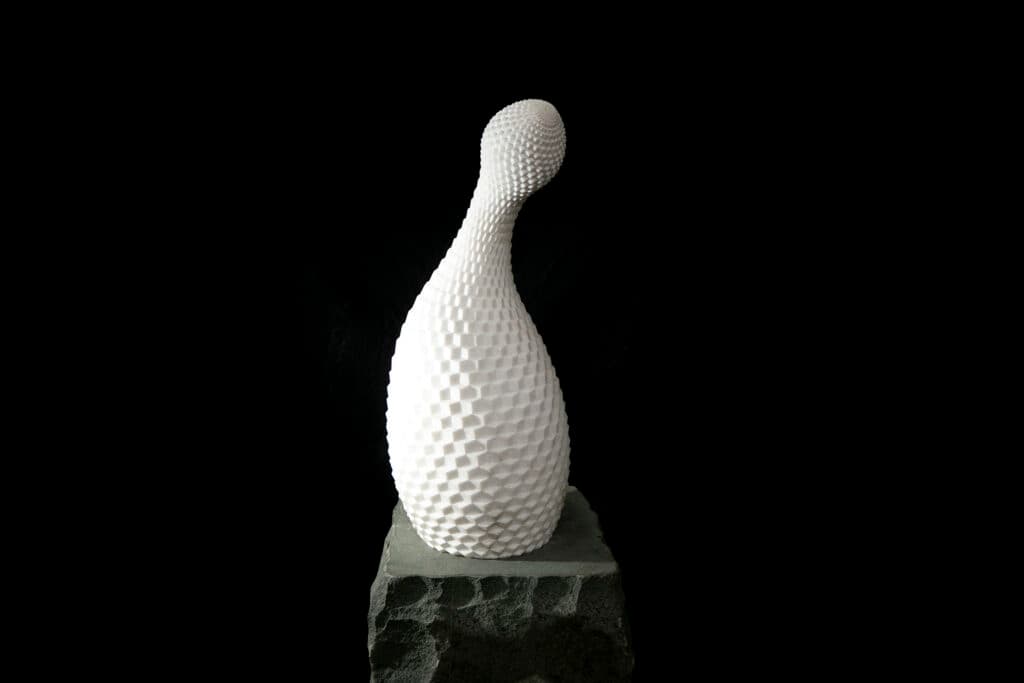

Camron has learned a lot about his father during this process, including Argent’s pioneering work in digital art and sculptures. Using digital design and 3D printing softwares like Rhino, MakerBot and Adobe, the storage was full of digital renderings of projects that would eventually be made globally in places like Sacramento, California, Shenzhen, China and even a Royal Caribbean cruise ship.

“In the beginning it was pretty sad,” Camron said regarding the decision to sell Argent’s work. “I’m kind of changing [my] mentality that these things deserve to be seen and deserve to be out in the public for people to appreciate. I don’t want to keep them hidden.”