Joshua Zielinski, a middle manager at a downtown Denver family homeless shelter, wakes up at 5:30 a.m. at his Arvada home.

He hopes to squeeze in time for himself and God before addressing the day’s obligations.

Zielinski has gut issues. Maybe from the coffee he once guzzled to stay present as a husband, a parent and the manager of a family shelter? Maybe from the stress that has pushed so many homeless service providers out of the field?

His gastroenterologist says he has to eat breakfast before doing anything else — even before he prays. So he makes his food and brews two cups of black tea. He reads spiritual texts while he eats.

In a bedroom corner, he prays for thirty minutes before his daughter wakes up and chaos erupts: dress, brush your teeth, eat, sure, you can have more brown sugar on your oatmeal if you just get going.

He prays for his three children and his wife, the shelter workers he manages, and the dozens of homeless families who live at Samaritan House, the downtown Denver Catholic Charities shelter where he runs the family program that often runs at full capacity.

Samaritan House is a three-story brick shelter across the street from Denver Rescue Mission and other shelters, clinics, and nonprofits in central Denver.

It’s a part of town where the city’s class divide is on full display. The organization offers emergency shelter for people in crisis and longer-term individual rooms, serving families, single women, and veterans.

For decades, people without homes have lingered on the street outside the shelters. More recently, developers have invested mightily in the neighborhood, and new, trendy apartment buildings have attracted residents saddened by seeing so much poverty on the sidewalks.

Those residents call the shelter regularly. Why don’t you help these people?

Helping people leave homelessness is exactly what the shelter workers do, even though they know the need is greater than what they can offer.

Each day, Zielinski prays that the families he serves can build a better life before their time in the shelter runs out. And the vast majority of those who call the shelter home find longterm stability.

Zielinski also prays for thousands more he and his employees cannot help — the ones they have to say no to, the people who live on the streets, those hooked on drugs, those struggling with mental health problems, those too violent to live in a group shelter, those the government won’t allow to work, those that need work to survive, those with eviction records, bad credit scores and no net to catch them.

Some families break the rules and have to leave. Others would rather live outside than in the spaces Samaritan House can offer them. Many never get in to begin with, as the shelter doesn’t have room.

He prays for them all.

In seven years of working at Samaritan House, Zielinski can’t remember a time when family rooms were empty and nobody needed a place.

Demand has only grown over the past year, as new immigrant families have sought to build a life in Denver, eviction cases have risen and the metro area has seen a hike in the numbers of people looking for homeless services.

Those include new immigrants fueled by hope for a better life in the United States and Denverites priced out of their homes who have lost any hope they had in the American dream.

They have different journeys, but without a home of their own, those who can’t get into shelter share the same cold concrete, the same snow, the same dirt. They receive the same answer to pleas for help: resource lists that often lead to other agencies handing out resource lists, the best so many overtaxed nonprofits and city agencies can offer.

Yes, Mayor Mike Johnston has pledged to end homelessness in four years. No, he’s not close to meeting that goal.

He’s brought 1,512 people inside, but most don’t have permanent housing and are still living in private rooms in shelters. That’s a fraction of the more than 30,409 people who accepted homeless services in the metro area in a 12 month period, according to the latest Denver Metro Homeless Initiative State of Homelessness report.

Johnston’s shifting some responsibility for a fix from the city to nonprofits. The overburdened staff at Samaritan House is about to shoulder more.

Zielinski prays before eating and again before bed.

He prays for the kids in the pediatric clinic, the ones whose greatest anxieties come not from homelessness but from trauma inflicted by school bullies. He prays for the unvaccinated kids suffering from diseases they should have never contracted. He prays for the families who have faith and those who have lost it or never had it to begin with.

He prays he doesn’t have to kick any families out over violence or threats of violence or abuse. If he does, he prays that it’s not an easy decision for him and his team. It should never be an easy decision. He prays his team members’ hearts are not hard, that his heart is not hard.

Every year, in his annual performance review, he sets a goal of pausing during his workday, going to the chapel a few doors down from his office and praying some more. He never hits his goal to his satisfaction.

He kicks himself for that failure to pray. Then he crosses himself and prays some more.

On a Wednesday in April, he prays with his team before they debate the operations of the family homeless shelter.

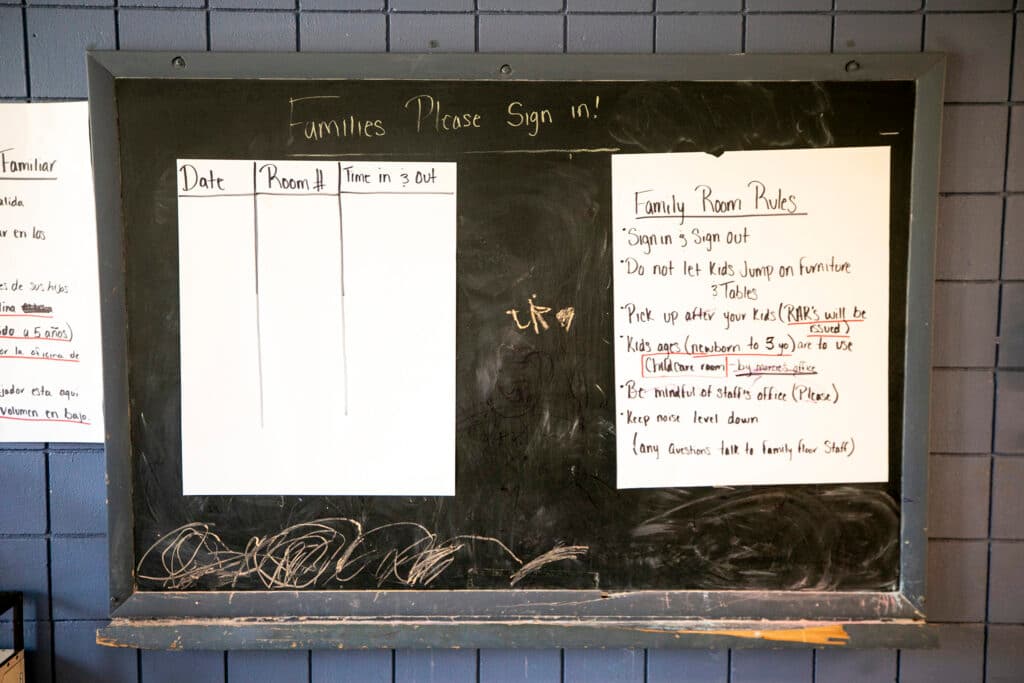

Who should clean up messes in the shared family room? Who left all those diapers? Would a wall-sized reminder to clean up help? Do people know how to clean up?

What sorts of food can families bring into their personal areas? How should they deal with picky eaters and kids with sensory issues?

Earlier in the day, an older resident griped that his pancakes were cold, that the hotplates didn’t work. Corporate needs to come in and eat the food, he said. Maybe the Archbishop? The Pope?

Staff weathers the gripes. They offer salt and pepper. They try to make the hotplates work. They let people figure it out.

Many families want to cook for themselves. After all, food connects families to their cultures, their sense of home. Of course, they should be able to make a meal — at least in a microwave. But letting guests use microwaves is more complicated than it seems.

Will the residents be able to handle the responsibility? Can they do so without making a mess? Should staff imprison the microwave if it goes uncleaned? If so, how can residents liberate it?

Is pizza too messy? Probably. Are Goldfish crackers okay? Sure. Do families have to go to the dining room every time they want a nibble? Absolutely not.

But food can cause pest problems. Food can smell bad and bother other guests. What’s the right balance?

Samaritan House isn’t just a family shelter.

There are homeless men and women without families. Some live in individual spaces with curtains instead of doors. Others crash on cots in crowded rooms. There are families with single moms. Some extended families are split between the types of housing.

On the third floor, families live in 25 rooms behind locked doors.

Another 14 families live on the first floor, down a dark corridor, walls between them, curtains giving them a hint of privacy and more exposure than most are comfortable with — something between a group shelter and an individual space.

Kids with autism struggle down there. Dads and boys over 12 can’t stay, because so many of the women and children, victims of domestic violence, are triggered by their presence. Even if families are allowed, some families feel safer and saner on the streets.

Zelenski says the pods are “not an ideal space,” but it’s the best the organization can do for now when demand is so high.

How long should guests be allowed to stay before they can reasonably be expected to get back on their feet? Six months? Nine months? More? Why isn’t there a clear answer? Are there exceptions? At some point, people have to move on.

How many classes should adults attend and what sort: Money management? Parenting? English? Workforce development? Therapy?

Who’s going to teach the classes? Do the workers really have the capacity to do so?

And who’s going to watch guests’ children while the parents are in workshops? Maybe the kids can also be in class? Perhaps they’ll play ukuleles?

Wait… infants need care, too. What good are ukulele classes for them?

In December, as hundreds of new immigrants came from the southern border weekly, 50 to 100 people knocked on the Samaritan House door each day asking for help.

Can you give me a water bottle? Can you give me a sack lunch? Can you give me a Coke? Can you give me a home?

For a while, the Samaritan House responded, until they started running low on food and clothes.

“That made a major dent in our supply,” Zielinski said. “And we can only give what we've got.”

Now Samaritan House gives out a granola bar, a water bottle and a reality check: I wish there was more for you. Let me tell you the reality. Let me tell you what your options are. Is there anyone you know that you can go stay with? Is there anybody, anywhere that you can relocate?

“You’ll have families where kids are begging and pleading that you bring their parents in,” Zielinski says. The response: “I wish we could do more for you.”

They can’t offer false promises. Doing so would be cruel. Even so, saying no weighs on the workers — especially those at the front door.

Can the work be better distributed among staff? Can the front desk catch a break? Can non-Spanish speakers help more with help from Google Translate? Will more staff quit, go elsewhere, leave the families in limbo?

The April meeting agenda is long.

Staff sing Happy Birthday and Feliz Cumpleaños to a coworker tuning in from Zoom on his day off. They do icebreakers. Then the meeting drones on, as a newly hired therapist learns what the family program does.

Every few weeks it seems like Josh and his team have to hire or train somebody new. Every few weeks somebody leaves.

Today it’s the career counselor. A few weeks back, a social caseworker left the organization to work as a chaplain. Another staff member who had been an attorney in Colombia got a gig in the city’s immigration services program, a step toward becoming a lawyer in the U.S.

Caseworkers nod off at the meeting. Zielinski tries to engage them with direct questions, but their minds drift to the families in crisis now.

As the meeting runs over time, staff bolt into action to handle an appeal from a guest who has been asked to leave over a dispute.

The staff meeting that began in prayer ends in a rush. The appeal begins fast. There’s little time to reflect.

Still, Zielinski prays — even if he doesn’t always know how.

Sometimes he prays the rosary or the catechism. He recites the Psalms. Other times, he just sits, confident others pray better than he does.

“I am so distracted,” Zielinski says. “I am not an expert by any stretch of the imagination. If I’m doing one thing right, I’m just forcing myself to do it, forcing myself to bring myself to that space knowing that faith in God will fill in the rest.”

His to-do lists are long. He spins his wheels. He tries to bring his family, his life, the work to God and give up some control. The process makes him dizzy.

He looks for God in the world, in the suffering, in the daily work, in others.

“Thy will be done,” he prays. “Take the work of my hands today and the mistakes I make. Remedy them. Take the good that I do, augment it, and let it be.”