On a February day -- the sort that tricks you into thinking it's warm enough to camp when blizzards could be on the way -- Yeslis Velazco stands on a Montbello median sandwiched between a liquor store and a Popeye's, near a City of Denver-run hotel where she and other new immigrants have been sheltering.

The tired, middle-aged mom and her family will soon be forced to leave this temporary refuge.

Where they'll go remains an open question.

Maybe a City of Denver-funded bus ticket will take them to yet another unknown city full of strangers. Or they'll end up on the streets, possibly an overcrowded group homeless shelter.

If luck strikes, she might get into an apartment with help from a nonprofit, though figuring out how to pay for it and avoid an eviction on her record will be up to her. If she finds work, that apartment could be home until her day in immigration court, where she could be ordered deported.

One thing is certain: The odds of succeeding in the U.S. are stacked against Velazco. Unlike some generations of immigrants in Colorado, many people like her from Venezuela generally don't have old friends and family in the country to move in with. Few people here can teach them how to navigate the immigration process and how to rent and make money without federal work authorization.

Beyond that, U.S. immigration law is not on their side. The paths most have taken rarely lead to permanent legal status, except for those who have strong asylum cases and legal representation. And even then, the high costs of a lawyer and application filing fees can be a bureaucratic wall for newcomers fleeing poverty and violence.

This reality is not what Velazco dreamed of back home in Venezuela as she pondered coming to the U.S. But her hope isn't gone.

Sure, in a few days, Velazco and her kids will be out of a place to stay, and she fears they'll join other new immigrant families living on the streets and in parks.

But even with homelessness around the corner, "little by little," Velazco says, her family is headed toward a better life.

That better life, though, is easier dreamed than obtained for many of the people already here and for those still on the way.

Current rules make it tough for immigrants to secure the right to work and long-term permission to stay in the country. While many have pending cases that could be years down the road in immigration court, many will likely lose.

"We have the system that we designed," explained immigration attorney Laura Lichter, "And it is designed not to work."

For new immigrants to receive work permits, they need to either have been granted parole by a border agent or have Temporary Protected Status, which is only open to those who arrived before July 31, 2023.

Those who have applied for asylum and have had an application pending for at least 150 days can also apply for work permits. But, between legal and filing fees, that process can cost thousands of dollars to start. And over the past three fiscal years, the courts denied about half of asylum cases, according to data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, a project tracking immigration court data.

While many are trying to follow these pathways available to them now, these statuses are temporary and do not grant permanent legal status or even a pathway to it -- with the exception of asylum.

Unlike those who arrived at Ellis Island in New York, where just about 2% of the millions of mostly European immigrants who underwent inspection were denied entry, just showing up at the border isn't enough for today's new immigrants.

And with a potential change in the presidency looming, many, if not most, are at risk of falling entirely out of status. If they stay in the U.S., they could end up resembling the undocumented immigrant population that has been here for decades.

What makes today's new arrivals different from previous immigrants

In the '90s, the last big surge of new immigrants coming to the U.S., many people crossing the border were from Mexico, explained Julia Gelatt, the Migration Policy Institute's associate director of U.S. Immigration Policy. They were largely single men, and many had friends and family already living here. Their culture had a strong presence here.

They also crossed into the country undetected and did not present themselves at the border.

Today's largely Venezuelan arrivals have fewer pre-existing social networks and larger families and are doing things differently.

"Most of them are now asking for protection when they reach the border," Gelatt said. "They're not trying to sneak across. They're trying to find a border official and present their need for protection."

By being transparent and following the law as best they know how, they hope the country allows them to stay and to work. But these immigrants are also easier to track and manage. In the likely case that their immigration claims don't pan out in court, or a new president shifts toward more enforcement-focused policies, they'll be easier to deport.

"Migrants aren't trying to hide and stay underground anymore," Gelatt said. "They've been processed, they're in legal proceedings, and they feel more comfortable asking for help."

Velazco hoped to find that help when she turned herself in at the border to the U.S., the same country recently run by anti-immigrant President Donald Trump.

Trump imposed devastating sanctions on Venezuela, over its main export, oil, in an attempt to push President Nicolás Maduro out of the power he continues to hold onto by subverting elections.

The Trump-era sanctions, continued under Joe Biden's presidency, were a broader application of other U.S. sanctions against Venezuela that go back to 2005. Sanctions have further damaged an already broken Venezuelan economy crushed by years of government corruption.

Velazco felt those economic impacts most of her life and wanted a solid education for her children, safety, healthcare, a home and a good-paying job. A better life might be possible in the U.S., and she hoped to contribute to the country as so many generations of immigrants have done before.

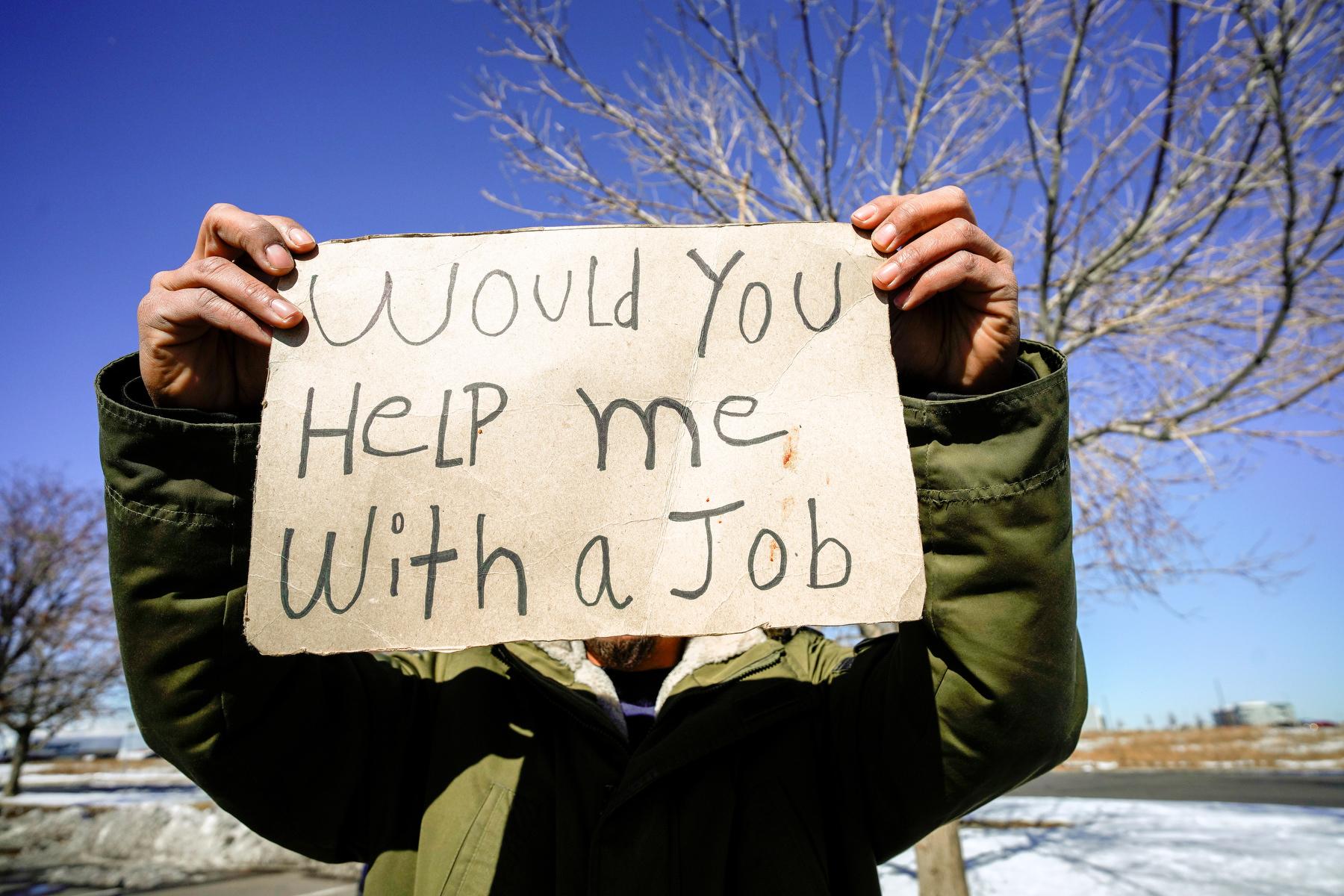

But facing homelessness, she's spending her days looking for a helping hand that sometimes comes and sometimes doesn't, when she'd prefer to be paying her own way.

Even if Velazco and other new immigrants were granted the legal right to work and stay in the U.S., they would face massive obstacles every Denverite encounters.

Citizen, legal permanent resident or not, the cost of living is out of reach for many working-class people. The city is 60,000 units behind what's needed in income-restricted housing, according to the Denver Housing Authority's former head David Nisivoccia. Wages have not caught up with the cost of living.

Finding and paying for childcare is a struggle for Denver's middle-class families, and without childcare, parents who would like to work can't.

Crime continues to be an issue, as does trust in law enforcement.

And many of the more affordable parts of the metro area have less access to public transportation, making getting to jobs both expensive and tricky.

Buying, maintaining and fueling a car -- a tool most Denverites say is currently necessary for getting around the city -- is costly. While new immigrants can purchase insurance and secure a driver's license, the process is slow, and saving enough money to buy even a clunker takes time when you fund it by washing windows or asking for change.

Velazco's family is far from alone in facing those challenges.

The city has helped more than 38,000 new immigrants, mostly from Venezuela, since October 2022, though nearly 20,000 have asked to leave the city by bus, plane or train, explained Jon Ewing, spokesperson for the Department of Human Services. It's unclear how many people who have left Denver shelters have decided to leave the city or state altogether.

More people are arriving every day -- even as the number of newcomers in Denver has slowed to between 20 to 30 people a day, according to Ewing.

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston has reduced recreation center and Department of Motor Vehicles hours and has asked other agencies to make drastic cuts to pay for aid. As of this week, Denver has spent almost $58 million on its response to new arrivals.

For months, Johnston also begged the federal government for more financial support, but that isn't coming any time soon after a bipartisan deal that would've made funding available to city governments failed at Congress earlier this month.

Families living at the shelter stand at the intersection of Peoria Street and I-70 and ask for money or offer to clean windshields. Across the city, this has become a common sight -- and for some long-term Denverites, a problem, even a threat.

The people trying to make money at stoplights and on corners don't want to bother drivers, said Velazco. Some are good, others not so good, but most are just trying to survive.

But the U.S. government won't let them work right now, so they do what they must to get by, secure money for work permits, rent, food and medicine for their children as they wait for court dates set for months -- even years -- into the future.

The city's resources are strained, and families are being pushed out of shelters. Overburdened nonprofit workers are scrambling to find places for them to stay, as politicians and residents in nearby cities spread panic that their communities will be "flooded," "inundated" and "overwhelmed" by new immigrants like Denver has been.

With the 2024 election coming, anti-immigrant rhetoric has become a political stumping point. Even Democratic rhetoric has pushed toward the right, as President Biden has said he'd shut down the border if he could.

How all that plays out in the future for these new immigrants is uncertain -- and terrifying for them, since they want to stay.

Meanwhile, politicians aren't generally the ones coming to help people get settled. Regular residents are -- and many say it's a struggle without a lot of official support.

Lydia Flynn, who volunteered to feed new immigrants and found herself taking a leadership role in the city's grassroots response that includes thousands, says Denver's government has failed to coordinate with those working on the ground to address the crisis.

"You're talking 12,000 moms and dads who have opened up their homes, who are feeding, clothing, driving people to doctor's appointments, driving them all over the city, trying to find them jobs, opening up their AirBnBs, their rental properties," she said.

Flynn says the city doesn't treat those volunteers as "a valuable asset."

"Maybe we don't work for the City," she said. "We don't get paid to do this work, but we're being called in our hearts to do this work, and we are here for the long haul."

Even so, burnout is setting in, and the few nonprofits the city is working with are overtaxed.

There's a lot the volunteers can't do.

New immigrants don't have access to affordable, quality health care beyond expensive, overtaxed emergency rooms and community clinics. Some suffer from chicken pox, stomach viruses and respiratory infections, and they are not able to get basic medicine to get better.

Volunteers like Flynn say they are ill-equipped to offer that too, so families suffer from treatable diseases or are sent to the emergency room, when a registered nurse would be able to offer what was needed.

And for many of the volunteers, their service to newcomers has been a crash course in how the U.S. immigration system works -- and doesn't. Even the city itself has been scrambling to keep up with the policies and possibilities afforded new immigrants.

As a result, some immigrant families have been given incorrect information about where they can take shelter, what shelters are open or closed, and where they can stay.

Families have been directed to shelter in facilities that aren't open without direction about a backup plan. Others have been given misinformation about how the work authorization process works, whether renting without income is a good idea, and how the city's rental assistance program might be an inadequate stopgap for longtime eviction prevention if a family does not have access to reliable income.

Some new immigrants have been given jobs where they have worked extreme hours and have gone unpaid.

Ewing said the city has been grateful for the volunteer response and is continuing to improve its work.

The city also recently hired Sarah Plastino, a human rights attorney who has worked for more than a decade with immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers, to oversee the new immigrant response through the Department of Human Services. The agency says it is consistently working harder to coordinate with volunteers.

"We do know there is always room for improved engagement and communication, and we will continue to work lockstep with the community toward this response," Ewing said.

Ewing said volunteers have also worked with the city at legal clinics for new arrivals and have been informed about how to help families that want to leave Denver get bus tickets paid for by Denver.

"It's a massive effort so I think people will always have additional questions, but largely I believe we're better connected with the community now than ever before," he added. "Our newcomer director comes into the job with fresh eyes and fresh perspective and I know she's excited to work alongside the community in addressing this response."

The response, from Denver, is a costly work in progress fueled by good intentions and a lot of uncertainty.

In many cases, the new immigrants are building social networks and supporting each other, while wrestling with trauma from a horrifying journey into the country and what could be a bleak future ahead.

Among those is Yonpier Tamoy, who on a recent February day watched as his son, wrapped in a black cape, got a a sharp fade in a parking lot from a Venezuelan barber longing to set up a shop in Denver.

Before coming to Denver, Tamoy worked in restaurants and served in the Venezuelan Marines before deserting his post -- a crime in Venezuela akin to treason, as he understands it. So he fled to Peru, where he lived for five years. He cooked for restaurants there, and he liked the country well enough, though he struggled to make ends meet and wanted more for his family.

So he moved on, taking the journey to the U.S. for the promise of a solid education for his children, three and nine. Before he left, he couldn't imagine how bad the trip would be.

Tamayo's children are the hundreds of thousands of new immigrants who traveled thousands of miles through multiple countries, crossed the Darian gap, a deadly jungle, risked robbery, kidnapping, rape and murder, survived cartels and smugglers, and crossed the embattled U.S.-Mexico border into the U.S.

Along the way, his children witnessed beatings, kidnappings and death.

"It was difficult because they got sick," he said. "They have trauma from the journey, from the kidnapping, from everything they experienced."

They've seen more death and hardship than most Americans experience in their lives just for a taste of something better in this country.

Was it worth the trauma of the journey?

"It's not something I'd recommend," Tamoy says.

Landing in Denver wasn't the first choice for most new arrivals -- just an accident.

Denver wasn't a dream destination or some sort of new immigrant utopia. Many people Denverite spoke to had little to no choice in coming to this cold, unaffordable state. They were put on a bus, possibly under false impressions provided by government agents, and they arrived.

Texas has been one of the biggest drivers. That state's governor, Greg Abbott, has bused thousands of people here since October 2022, spending at least $148 million along the way. Abbott argues other states should shoulder more responsibility for new arrivals.

Former Mayor Michael Hancock and now Johnston have called Denver welcoming and the city government has taken political hits from surrounding communities, including Aurora, Lakewood and Colorado Springs.

While Denver's official policy may be "welcoming," the signs in the shelters are blunt: Move on to another part of the country or risk freezing outside and face arrest.

Inside the shelters, guests say they get yelled out by burned-out staff. The families' movement is carefully surveyed by security. Their rooms are subject to late-night searches, where staff make sure they aren't hoarding used clothes or perishable food, even as children struggle to sleep, sometimes due to hunger or illness.

Shelter staff refuse to let media onto the premises and will not talk about what's going on inside.

Residents say they fear being kicked out by staff if they speak to reporters, though Ewing of the Department of Human Services, says that's not a policy.

And everyday Denverites don't always show hospitality. As families try to ask for money or offer to clean windshields, they're harassed, flipped off and threatened.

"The people here see us like we're a plague," Velazco said. "We are not a plague. We are families. We are humans."

Velazco still sees hope in the American Dream, though her life is currently worse than it was in Venezuela.

"This is not a life for my children," she said. "This is not a life for anyone."

Some people have come to the U.S. to do good and contribute, but she fears others have been put in economic situations where they will inevitably do bad -- to pay for food, to pay for medicine, to pay for life.

She hopes she'll move toward a better future but also fears the promise of the U.S. is an illusion and that creating a good life here will not be possible.

If a better life is not possible, if she cannot find housing, if the courts ban her and her children from staying, she fears what her family will go through, and she doesn't see an escape.

"I'm trapped in a bubble that doesn't give me any options to leave."