Denver’s cracking down on people experiencing homelessness since Mayor Mike Johnston celebrated moving 1,000 people off the streets in December.

City data, attained by the Housekeys Action Network Denver (HAND) and civil rights attorney Andy McNulty, shows that warnings and enforcement of laws regarding trespassing, urban camping ban and solicitation near roadway, were up significantly in January through March of this year.

“From January through March of 2023, there were a total of 694 enforcement actions for these anti-houseless ordinances,” HAND wrote in a report about the data. “Those same three months in 2024 showed 1,017 enforcement actions — a nearly 50% increase (46.5%).”

Terese Howard, a longtime homeless advocate with HAND, said the data reflects what her group is hearing on the ground: She says people tell her that police are threatening, ticketing and arresting more unhoused people than at any time in recent history, and the Street Enforcement Team, the unarmed group that has the power to cite and ticket people, has increased its enforcement, too.

“From the beginning of this effort, we were clear that we would enforce the permanent closure of former encampments and that camping would no longer be allowed in the locations that have permanently closed,” wrote Johnston’s spokesperson, Jordan Fuja, in a message to Denverite. “Our teams, along with city partners, are enforcing those closures while working to connect even more Denverites to safe, stable housing options and support services.”

It’s unclear whether the increase in ticketing is a direct result of that long-promised policy of keeping closed encampments closed or a wider-spread approach to how the Johnston administration is addressing homelessness.

The mayor declined requests for an interview about HAND’s criticisms, the data, changes in enforcement policy, and conversations between his office and public safety leadership, or how enforcement relates to his House1000 initiative.

Johnston’s encampment closures have received mixed reviews.

The policy has been embraced by some Downtown Denver residents and businesses, who spent years advocating for a more muscular response to homelessness.

“We continue to applaud Mayor Johnston’s swift, bold action to address unsheltered homelessness in our center city, and beyond,” wrote Kourtney Garrett, CEO of the Downtown Denver Partnership, a business booster group that collaborates with the city on safety issues, adding that the policies have brought “a sense of renewed energy” to downtown.

But for unsheltered homeless people, Howard said, the rise in citations has led to an increase in warrants and jail time, while the process of securing housing options can take an unhoused person more than two years. Affordable housing is simply in short supply.

“People are in constant motion, constant distress, losing property,” she said. “It's just devastating to people's lives.”

Former mayoral candidate Lisa Calderón said people experiencing homelessness in the city center are being pushed from downtown to suburban neighborhoods like Montbello — communities with fewer resources.

McNulty, the attorney, described the city’s increased enforcement targeting homeless people and forcing them to move on as “unconstitutional.” He’s weighing whether to take legal action.

Meanwhile, many unsheltered people say they are not offered housing or long-term individual shelter that people received if they were living in the encampments Johnston closed.

By the numbers

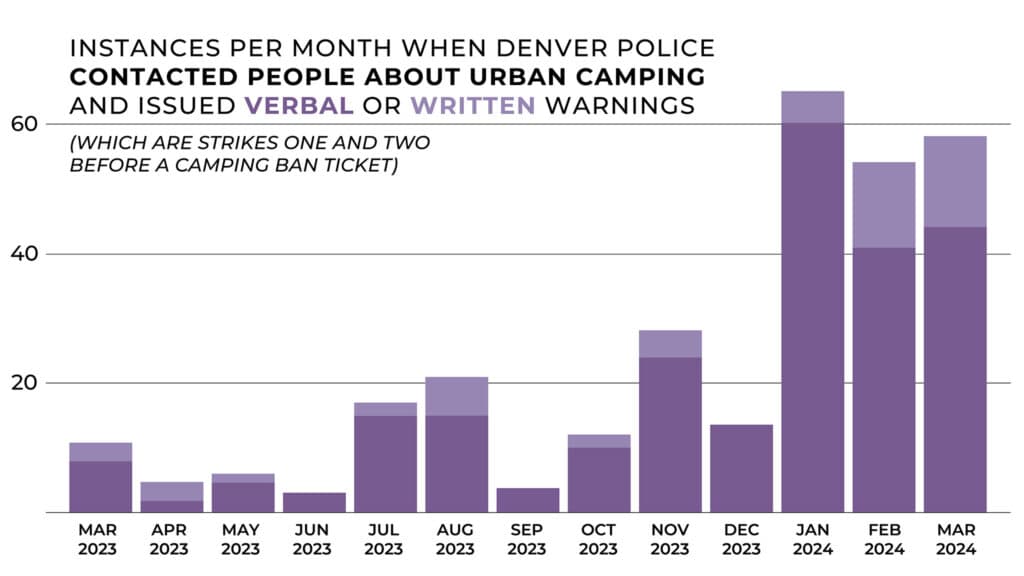

The number of times that the Denver Police Department responded to an encampment and issued a warning nearly tripled from March 2023 to March 2024 to nearly 60.

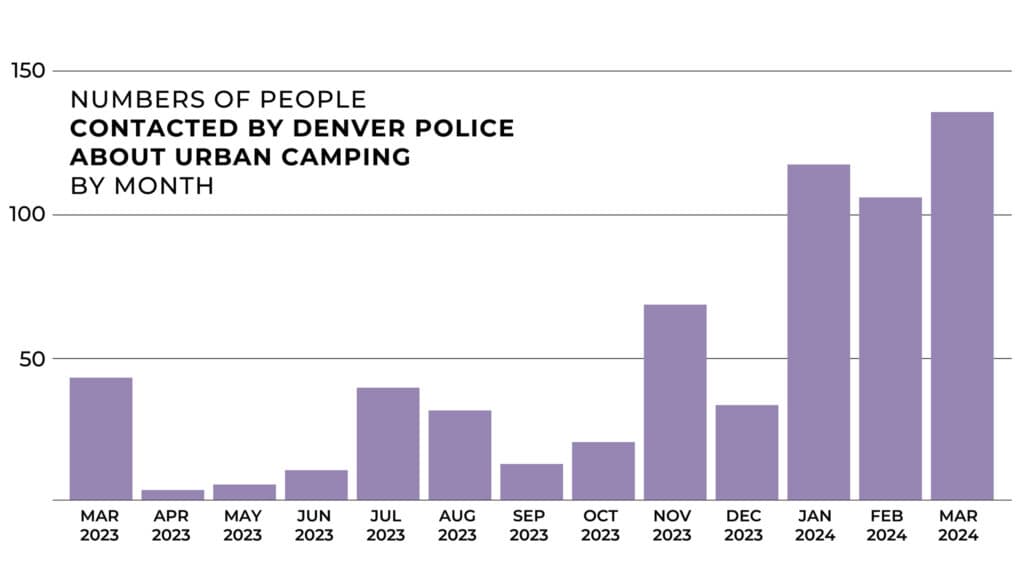

The number of documented contacts between officers and people experiencing homelessness nearly tripled in the same time period to just under 150.

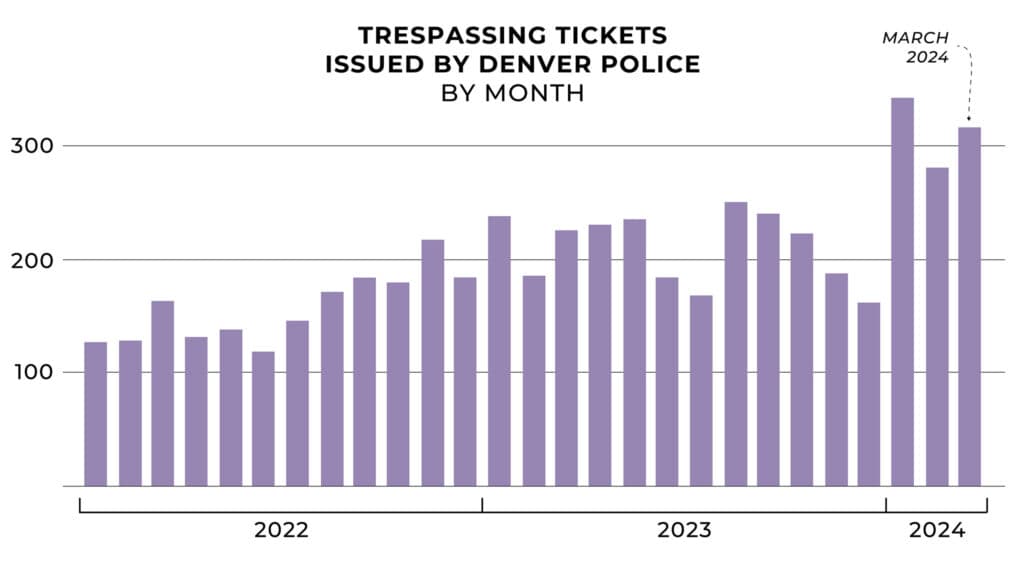

From January 2022 to March 2024, the number of trespassing instances also nearly tripled.

Urban camping ban enforcement has increased since January, but it’s hard to say by how much, because the city’s methods of tracking this data have been inconsistent.

“After receiving this data from the police department, city attorneys informed us that the police department was not consistently tracking camping ban enforcement of ‘move on’ orders and warnings until recently ‘due to the direction being given that the ordinance was not being enforced (meaning they were not typically citing or arresting for violations),’” according to the HAND report.

A note HAND obtained from the city attorney’s office indicates that the suspension of camping ban enforcement was lifted in the spring of 2024.

“This will likely lead to the most camping ban enforcement ever since its passage,” HAND speculates.

Fuja said there’s been no formal change in policy.

“I wouldn’t really say it’s a shift because we’ve said this the entire time — at the sites that are permanently closed, we’re enforcing the closure,” she wrote.

Johnston’s efforts to house 2,000 people by the end of 2024 have had mixed results.

House1000 was Johnston’s effort, in his first six months in office, to bring more than 1,000 people living in encampments into individual shelters like motel rooms and tiny homes or immediate housing through vouchers or connections with friends and family by the end of 2023.

In early 2024, the administration renamed the effort the more accurate “All in Mile High,” since the majority of people were not receiving housing and many were still homeless by federal definitions.

According to the city’s dashboard, Johnston’s administration has successfully housed just 32% of the 1,564 people brought inside. Another 49% are still in the All in Mile High shelters.

Of the 354 people who exited the city’s All in Mile High shelters, roughly 70% had a bad outcome: 165 have returned to the streets, 28 are in jail and 10 died. The city lost track of 47 individuals who were part of the program.

The program had some successes: 22 people were reunited with family or friends, 7 found “other” stable housing options, 26 went to group shelters, 45 went to leased units and 4 went into treatment.

Fuja also noted the administration has reduced the number of large-scale encampment sweeps.

“Since day one,” she added, “this administration has aggressively responded to one of Denver’s toughest challenges with a multi-pronged approach that prioritizes getting people indoors and has since helped more than 1,500 Denverites get off the streets and into housing while permanently closing 14 encampments.”

But for people living outside, the mayor’s efforts are cold comfort.

Unhoused people are “getting swept, getting swept, getting swept,” Howard said. “And people are pretty torn apart right now on the streets due to this.”