Updated April 7, 2025 at 2 p.m.

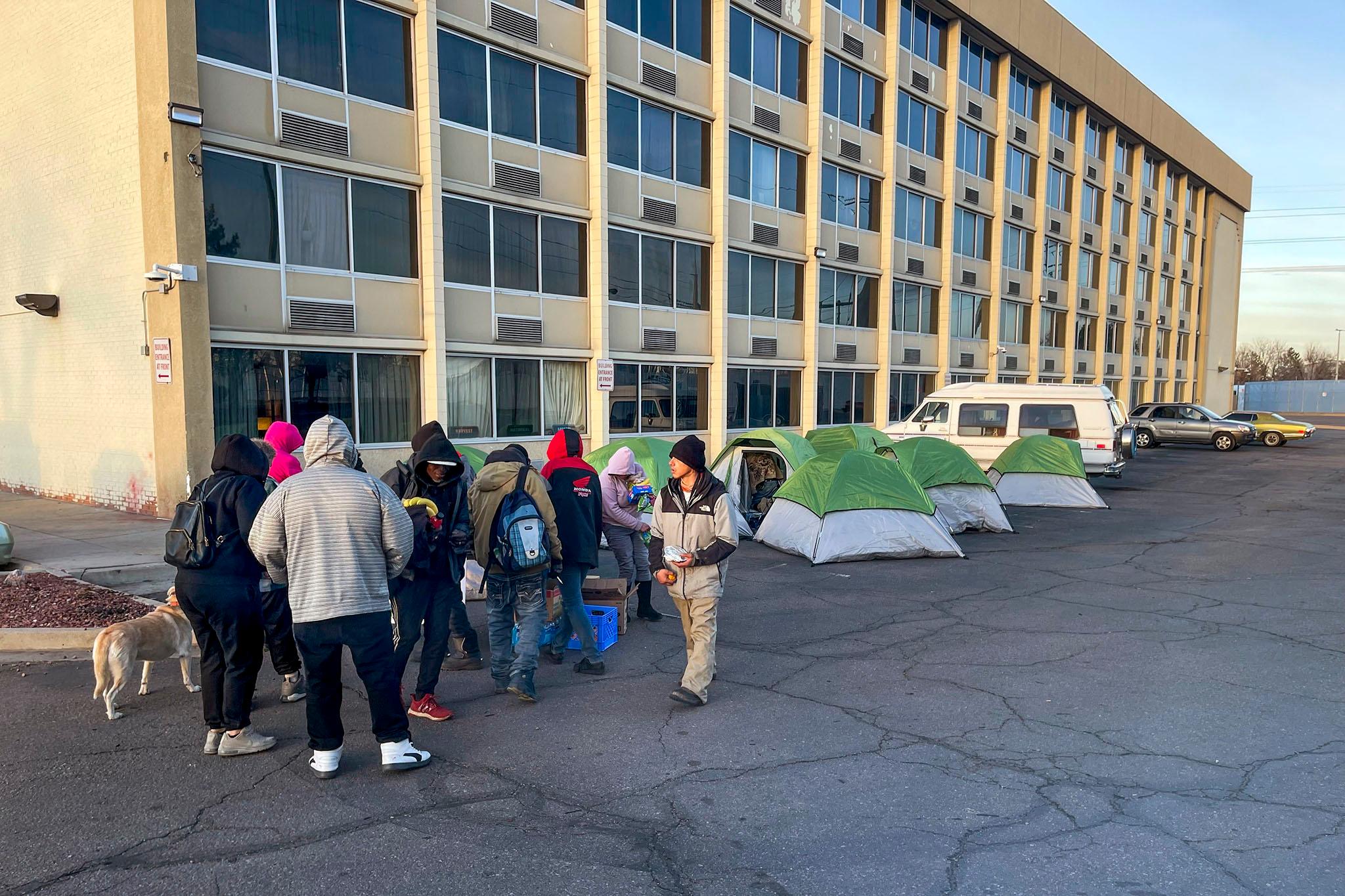

Aurora’s Dayton Street Day Labor Center was unusually quiet for a few weeks this year, after federal raids drove away immigrants who came for help applying for work authorization and finding jobs.

It was a worrying sight for Dayton Street’s staff — especially with Tax Day approaching.

The organization had been preparing to launch free clinics to help their clients file returns. Even immigrants without work authorization are required to pay.

So organizer Kadi Kouyate spent weeks calling people, one by one, trying to convince them to come back. And they did. For one week in March, the little building off Colfax Avenue brimmed with people ready for help with their paperwork.

“It was complete chaos here,” said Kouyate, who spent more than a decade helping immigrants with taxes before she brought the service to Dayton Street.

She was glad to help — but she knows her client’s fears weren’t misplaced.

President Donald Trump’s administration is attempting to use tax filings to pursue people for deportation, despite the fact that the Internal Revenue Service is required to keep records confidential under federal statute.

It’s another threat to a population that’s endured performative shows of force by federal agents and rancorous political rhetoric — and it’s not the first time tax records have been used to target immigrants in Colorado.

Paying taxes feels increasingly risky for undocumented immigrants.

This was the labor center’s first year offering free filing help. Kouyate said the people who crowded into the space proved the service was needed, once they felt it was safe.

“They still have the fear to come over and ask for services, because they don’t know what’s going to come tomorrow,” she said.

A client named Ndiaye, who arrived in the U.S. two years ago after leaving home in Mauritania, said he understands that fear. He asked us not to use his last name, concerned speaking up might put a target on his back; February’s federal raids were still on his mind.

Still, he was pragmatic about the perceived risk.

“The government is the one that gave me the work authorization. I don’t think I can hide myself, and I wouldn’t think it would be good sense for me to hide myself,” he said in French as Kouyate translated. “I don’t think I’ve done anything wrong. I’m here to get protection.”

Despite their misgivings, Kouyate impressed upon the people she called: This was something they needed to handle.

Most of her clients, like Ndiaye, are pursuing asylum claims and have gotten work authorization through that process. While some are worried filing returns might attract the government’s attention, the consequences could be worse if they fail to pay.

“They still have to do the right thing, no matter what,” she said.

President Trump is trying to use the IRS’ paper trail to aid in mass deportations.

The fear Kouyate encountered isn’t just rooted in hysteria. News has emerged in recent weeks that the White House is working on a deal to extract personal information about immigrants from the IRS.

The deal reportedly would allow immigration officials to submit names of people they’re pursuing to the IRS. The agency might then provide addresses, phone numbers or employment history to help officers find and arrest those people.

Doug O’Donnell, the former IRS commissioner, denied a White House request for information about 700,000 people in February, a day before he retired. The agency’s new head, Melanie Krause, is reportedly more open to the idea.

The new push echoes a 2008 fight in Colorado, when Weld County officials searched a Greeley tax preparation office and took information on 4,900 clients, many of them immigrants. Local authorities said they would use the information to pursue some 1,300 people, but a lawsuit from the ACLU of Colorado stopped them.

“They had to destroy their notes. They had to stop going to the grand jury for indictments based on the information that they had seized illegally,” recalled Mark Silverstein, former legal director for the ACLU of Colorado. “That's such an over-broad intrusion into the privacy of innocent people.”

What taxes do immigrants pay?

Kathy White, executive director of the Colorado Fiscal Institute, said immigrants do pay taxes, despite myths that they don’t.

“The bulk of taxes that they're paying are consumption taxes,” she said. “Just like you and me, they pay sales tax.”

Anyone who works is also required to file income tax payments, she added, even if they can’t work legally.

While most of the 40,000 people who arrived here from the border in the last few years were released by Border Patrol to pursue asylum claims, and therefore have pathways to work legally, it can take months to get an official green light to earn money. Some resorted to fake or stolen Social Security numbers to get jobs and earn money.

The federal government recognized the need to allow tax filings from people without work authorization, White said, when it created Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers in 1996. It’s a way to track tax payments for people who do not qualify for Social Security benefits.

White’s nonprofit estimates that immigrants in Colorado pay over $40 million in state in local taxes each year, and represent 10 percent of all cooks, 20 percent of all construction workers, 25 percent of all janitors and nearly half of all housekeepers in the state.

While White said immigrants’ contributions are crucial to Colorado’s financial health, she said most new arrivals — authorized to work or not — must wait years to access public benefits like food stamps.

“They contribute to Social Security and Medicare, even though, for many undocumented immigrants, they will never ever be able to claim those benefits,” she said.

And she worries about what Trump’s deportation push will mean for the state and the nation’s finances. Colorado is counting on immigrants' payments into the tax base, and their labor.

“You can't just deport every immigrant or even green card holder in Colorado without some serious economic impacts that would affect everybody,” she said. “We need those people. We need to educate them so that they can replace an aging workforce.”

Editor's note: This article was updated to correct the spelling of Kathy White's name.