The backers of Denver’s professional women’s soccer team are ready to spend unprecedented sums to bring the National Women’s Soccer League to the city.

In a matter of just a few months, the owners of the unnamed team have announced plans that could total some $400 million — and that’s before they even start paying the soccer players who will soon play at facilities planned for Centennial and Denver.

It’s one of the largest proposed investments in women’s soccer in the U.S. and the world — one that could combine hundreds of millions in private investment with tens of millions from local taxpayers.

“We want to prove that if you make the same investment in women athletes that we've made in men athletes, that you can increase performance and that you can run a franchise in a way that creates revenue opportunities that are unique and different than what has traditionally been done,” said Rob Cohen, the primary owner of the team, in an interview this week with Denverite.

But in the world of soccer, even if you build it, profits may not come. Soccer, as experts tell Denverite, is a game of passion where financial success doesn’t come easily. They say this historic investment could be a gamble for its wealthy backers, local governments and the people of Denver.

Here’s what we’ve learned about the ambitious plans for the team, which could be playing in Centennial next year before moving into its permanent home in Denver’s Baker neighborhood by 2028.

Meet the owners.

A team with a diverse portfolio of investments and experience is behind Denver’s NWSL bid. Investors include a former Washington Commanders executive, a former Starbucks board chair, and several local entrepreneurs.

Cohen is the primary backer of the team. An insurance and investment executive by day, he has developed a lifelong affinity for Denver sports.

In 2001, he founded the Denver Sports Commission, which has since become a part of Visit Denver, the official marketing agency for Denver tourism. He has also led efforts to bring the Olympic Games to Colorado.

For Cohen, owning an NWSL team is the culmination of all those years of work.

“This has been a long time coming for a lot of us that have worked tirelessly on this for not only just a couple years, but literally for decades,” he said at the team’s launch event in February.

Cohen and company outlined ambitious goals for the team. They promised championships and a strong relationship with the community. They also promised profit — for both the team and its community.

“Everything that is happening in this area of women's sports and that will happen right here in Denver benefits communities, benefits society,” said Mellody Hobson, one of the owners and former board chair of Starbucks. “And we are again, so excited to be a part of it, and also at the same time to generate great returns for our investors.”

The investment thus far.

Denver was one of three finalists the NWSL identified to host its 16th team.

To overcome competing bids from groups in Cleveland and Cincinnati, Denver’s ownership offered to pay an expansion fee of $110 million, according to a city presentation — more than double the fees reportedly paid by Boston and the Bay Area’s NWSL teams just two years ago.

While it’s one of the highest fees ever paid for a women’s team, Denver’s fee still pales in comparison to expansion fees in American men’s leagues. The newest Major League Soccer team, San Diego FC, paid $500 million to secure its spot in 2023.

“I'm not going to talk about the franchise fee,” Cohen told Denverite. “What I can tell you is what the ownership group’s mindset is. We're all business people. We sat down and we ran the business models and the pro formas on it.”

Cohen said that what makes the business plan “a little bit unique” compared to other NWSL teams is its focus on other revenue streams besides soccer on the pitch.

He was referring to the investments the team is planning for the new stadium, which could anchor a larger redevelopment around Interstate 25 and Broadway.

“Traditionally, what you see, if a women's team is playing in a city-owned venue or a venue owned by a men's team, they're paying rent, but they're not getting an opportunity to share in the revenue streams, whether that's the naming right of the stadium, whether that's the pouring rights, whether that's the sponsorships, other events that exist,” Cohen said.

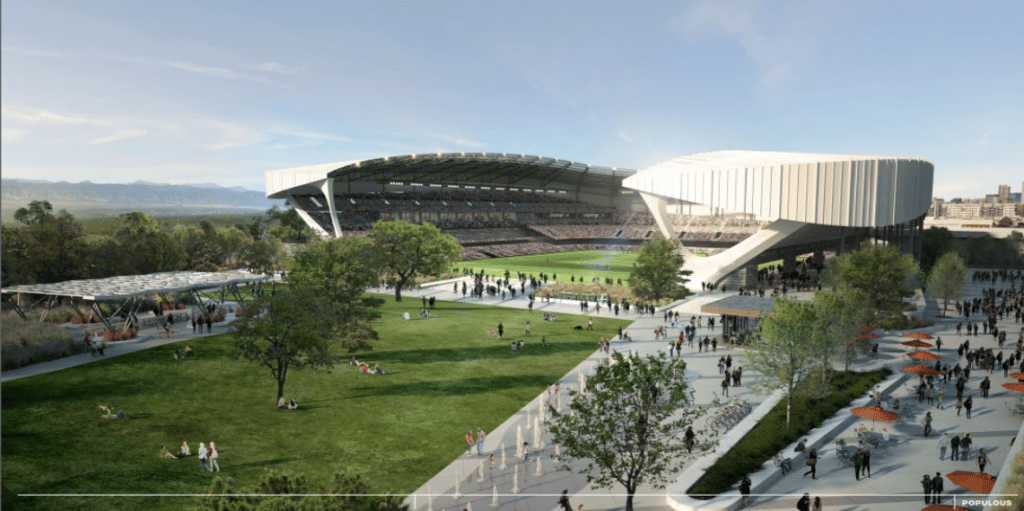

It would be one of the first stadiums in the world to be built specifically for women’s sports, following CPKC Stadium in Kansas City in 2024.

Officials have said construction on the planned 14,000-seat stadium in Baker will cost between $150 and $200 million. The team's investors would be responsible for getting the structure built, but the city of Denver is proposing to add another $70 million to buy the land for the stadium and build infrastructure improvements in the surrounding area.

Cohen and the team also plan to ask for tax benefits for construction of the stadium itself. They want access to tax increment financing (TIF), a tool the Denver Urban Renewal Project commonly uses to finance development. Under the TIF model, when a project generates new tax revenue, that money can be used to fund infrastructure specifically for the project, rather than going into the local government’s budget.

“As an ownership group, we're not planning on any TIF as a part of it, but if the overall project is successful, then we should participate in it just like everybody else and because we're going to be the catalyst for it happening,” Cohen said.

Meanwhile, the team has unveiled plans to build a temporary stadium, training grounds and a corporate headquarters in Centennial, which will cost up to $25 million . The team is planning to split the costs with the local school district, eventually handing the stadium over to the schools.

Between the franchise fee and stadium plans, the team's efforts could surpass $400 million of private and public spending, all before it has released its branding or signed a coach and players.

It’s an aggressive bet on women’s sports — one that Cohen said will bridge the gender divide.

“We're out to prove that hypothesis wrong, that women's sports has to be, for lack of a better word, a charity, that it can be run like a business and that we can put a winning team on the field and do something great for our community all at the same time,” Cohen said.

Can Denver’s NWSL team profit?

Some experts are skeptical of the team’s bet, warning that soccer — and sports in general — often attract risky investments by governments and private investors.

“Football, it is the most incredible mistress of club owners,” said Kieran Maguire, a finance professor at the University of Liverpool. “It turns them from rational, sane, profit-maximizing businessmen into simpering, gibbering wrecks.”

Maguire wrote the 2020 book “The Price of Football” and hosts a podcast with the same name. In a world of soccer fanatics, he has positioned himself as someone who both loves the sport and intimately understands the finances behind it.

He’s come to understand soccer, or football as he calls it, as an industry that is designed to lose money. He describes it as a “trophy asset industry,” where owners often choose passion over profit.

Maguire said soccer team owners have three major revenue streams that can lead to profitability: stadium attendance, commercial revenue, and perhaps most importantly, broadcast rights.

The NWSL’s current broadcasting deal with CBS Sports, ESPN, Prime Video and Scripps Sports is $240 million split across all the teams for four years, according to reports from sports publications. That’s a fraction of the lucrative broadcast deals signed by men’s leagues. The other major professional women’s league in the U.S., the WNBA, signed an 11-year media rights deal valued at $2.2 billion last year.

Maguire said his “biggest worry” is whether the NWSL could negotiate a more lucrative deal in a crowded sports broadcast market.

“The major U.S. broadcasters, they'll be focusing on NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB and so on,” Maguire said. “After you've paid for those rights and after those particular sports have taken up their prime slots, what you've got left, it isn't a huge appeal to broadcasters, and I think that will be reflected in the value that they're prepared to pay at present.”

Cohen said that while the team’s model is built for eventual profitability, he acknowledged it likely won’t happen soon.

“I don't see an immediate pathway,” Cohen said. “There are certain things that need to happen at the league level to contribute to this in terms of the media rights and other things that we've seen other leagues and other women's leagues do.”

Even if the team isn’t immediately profitable, can the stadium put money into Denverites’ pockets?

Many fans will never think about the record franchise fee or historic investments in Denver’s new soccer team.

Perhaps more tangible to the average fan is the planned stadium, which will become the hallmark of Denver’s Baker neighborhood. Owners and city officials have argued the stadium will breathe new life into a long-vacant part of the neighborhood.

“We wanted it to be centrally located in Denver,” said Mayor Mike Johnston when the stadium’s location was announced. “We wanted to be in a place where it could catalyze a real neighborhood of development around it.”

During a routine public comment session at Denver City Council in mid-April, business owners approved of the mayor’s plan.

“The activity, the revenue this completed project will bring to the South Broadway corridor are too large to list at this time,” said Ryan Fleming, a co-owner of Joe Willy's, a sports bar on South Broadway. “Currently, this is an optimal time to hyperboost the neighborhood economy, the city economy, and all of the capital outlays in the area.”

It will also come at a price to taxpayers. Mayor Johnston and his administration plan to dedicate $50 million of the city’s property-tax-funded Capital Improvement Fund to purchasing the land under the planned stadium. Under the deal, the city will own the land and have an option to purchase the stadium, which would ensure its accessibility to the public should Denver’s NWSL team leave the market.

The city also plans to spend $20 million on infrastructure improvements for the surrounding area, such as sidewalks, streetlamps and an eventual public park. City officials say those projects were necessary with or without the stadium. The stadium also could get additional taxpayer support through the potential TIF arrangement.

The administration still has to convince the Denver City Council to support the plan. The argument is that the $70 million of taxpayer investment will pay dividends through increased consumer spending fueled by the stadium, while also improving the neighborhood.

One expert Denverite spoke to cast doubt on the lofty promises the city has made. Geoffrey Propheter, a professor of public affairs at CU Denver, has devoted much of his career to studying stadiums’ financing and their impact on surrounding communities.

Propheter said the public paying in any fashion for a sports stadium — whether it's voter-approved property taxes to build Coors Field or using discretionary funds to buy land — is like throwing a house party.

“When you subsidize sports, you are subsidizing a party,” Propheter said. “Who doesn't love a house party? But the owner, the administrator of the house party, has to incur costs. You need to go buy streamers and beer.”

“And unless you charge a cover charge at the door, then you are losing money,” he continued. “But that's not why you're having the house party. You’re throwing the house party for the community and socialization and it's fun.”

The city argues that it's moving cautiously. It will own the land and have the option to buy the stadium, giving it an option to repurpose the area if the soccer team fails or moves. But Propheter said that would leave the city responsible for a major expense.

“It is not a good thing to become the owner of a giant steel paperweight that has no use, that’s 30 years old,” he said.

The city’s finance department published a study that found that over the next 30 years, the stadium could generate over $500 million in tax revenue from spending in and near the facility.

However, exactly how much of that will benefit nearby residents and businesses is unknown. The study noted that while spending in the area will increase, it may simply redirect economic activity from other parts of the city.

There is also a possibility that the stadium ends up gentrifying the area. Various studies that Propheter has completed found that commercial rents increased in areas where stadiums have been built. One study found that independent businesses had their lifetimes cut in half after Golden 1 Center in Sacramento opened.

The team is getting ready to play.

While Denver City Council will continue to debate the city’s financial role in bringing professional women’s soccer to the city, Cohen said the team’s work will continue.

“The goal is to have the temporary stadium up and ready to go for play next year and the permanent stadium, assuming everything moves on the schedule that we currently have, will hopefully be ready in March of ‘28,” he said.

The team has recently made its first hire — Jen Millet, a Denver native, will serve as its president, joining from Bay FC.

But the team still needs to announce a name, hire a head coach and find the players who might lead it to glory — and profit.