A crowd gathered as Meredith McBurney plucked a bright, squirming yellow warbler from a net.

“He’s so cute!” someone whispered.

“That's a good bird,” McBurney said to him as she loosened fibers wrapped around his foot. “This one got pretty tangled.”

She slipped him into a drawstring bag, then led her human guests back to a shelter nestled in the trees.

It was just another spring day at the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies’ banding site in Littleton. McBurney has led work here since the Denver Audubon Society’s Kingery Nature Center by Chatfield Reservoir started in 2008.

The warbler wore a metal anklet, proof he was already part of something much bigger than himself. He was being tracked for science, one of millions whose movements, schedules and health are tabulated each year around the continent.

McBurney loves this work, even if the research she fuels can be discouraging. The numbers show birds are in a moment of crisis. She can see that here in these woods, where she also finds hope for their future.

She pulled the warbler out of the bag, feet-first, to get a better look.

Yellow warblers are “the Denver summer bird,” McBurney said. No other bird is caught more here each spring.

And they’re most welcome: they’re vibrantly cute, and they do not bite.

“I mean, he just looks like he hasn’t a care in the world,” she said, as she carried him to people standing around her picnic table.

A class was here from Colorado School of Mines, sustainability engineers with a flair for nature.

McBurney measured his wings and tail, then pinched him to see if he had any fat left from the winter. She read off numbers etched into the metal cuff around his tiny talon. Volunteer Kyra Munz penciled the data into a notebook.

When she was done, she placed the bird in someone’s hands. In a sudden flick of his wings, he was gone.

The information gathered here feeds databases on migration and population that help researchers keep tabs on species around the world. Bird Conservancy of the Rockies has a license to catch and count during migrations, both in Littleton and at Adams County’s Barr Lake.

The scientific outlook hasn’t been great lately. A 2019 study estimated North America lost almost three billion birds since 1970. Outdoor cats are a major factor. Climate change is also messing with migration rhythms. Migrating birds might find that their old nesting areas have vanished at the end of a long flight; McBurney’s warbler may have come from as far as Mexico.

“He can have a perfectly wonderful habitat down there in the winter, and he comes back here and finds out that his city, state park is no longer that — and is a housing development,” she said.

She said she’s felt the broader population decline over the years here.

“They're arriving on schedule. The problem seems to be that there aren't very many of them,” she said. “We are seeing fewer birds every year.”

While her data show both ups and downs, the trend at this location is mostly down, she told us. It’s too early to say how this year compares, but she’s heard from colleagues across the state that nets are emptier elsewhere, too.

Data like that can be hard to handle if your life revolves around birds.

McBurney found that passion later in life.

“I was 50, and I didn't know a house finch from a flicker,” she said. “This was a midlife crisis for me or something.”

She spent years leading nonprofits, but felt her life change direction after she took a trip to Venezuela to help band long-tailed manakins.

“Somebody put a black and white warbler in my hand, and that was it,” she remembered. “I didn't want to go home. I was ready for a change.”

Hearing her speak, it’s obvious McBurney hasn’t lost that flame in her two decades with Bird Conservancy. She’s so dedicated not just because she loves these animals, but because she worries for them, too.

“Everybody who does this does this because they love birds,” she said. “And I was thinking about this driving out this morning — the overpowering problem of, ‘How does one individual have any impact on anything going on in the world?’”

And yet, she said individual action is where she finds hope. People can better manage their cats, or plant native vegetation in their yards, or advocate for fewer pesticides in their communities. When strangers come to visit, she can inspire them. That helps free her from existential dread.

“I'm not asking people to donate money. I'm just asking them to care about this bird that's in my hand, which I find quite easy,” she said.

Open programs like this are meant to make a difference.

Nicole Bopp, executive director of Denver Audubon, said programs like McBurney’s play a key role in their strategy to help bird populations rebound. It’s about getting people “bird-curious,” she said, willing to take small steps where they can.

“Bird banding is an incredible way to connect people to the process and the research,” Bopp said. “That can really start your relationship with connecting to birds in your own backyard.”

And backyards are key, she emphasized.

Habitat restoration is Denver Audubon’s main focus in this fight, but Bopp said they know purchasing land is probably a difficult goal in the metro’s hot market. Instead, she said there’s great untapped potential that just needs activation.

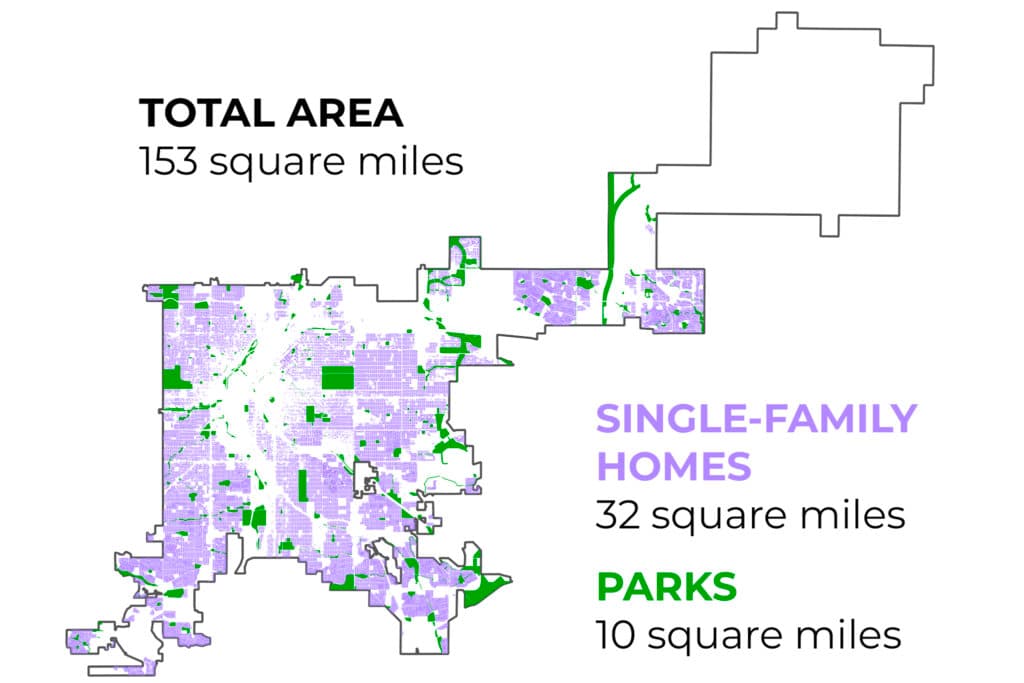

“I keep thinking about the hectares of land in Denver that are backyards or parks,” she said.

She’s not wrong. Single-family homes make up a fifth of the city’s land use. Denver property data suggest these homes only consume 26 percent of their parcels, on average, which means their yard space amounts to as much as 16 percent of the city’s total area. (This is just the total parcel size minus the area of above-grade structures, so “yard” here still includes driveways, pools and porches.)

“We could create a really diverse habitat just in every park and backyard, if we would just look away from these monoculture lawns,” Bopp said. “It’s about staying positive and understanding you do have an ability to create a better habitat.”

McBurney said inspiring that positivity is easy when you’ve got a pretty bird in your hand. Some people, like her, can’t get enough. Kids have come back for years, and she’s loved watching them grow into adults and active volunteers.

She likes most when families come to learn, and learn to care, together.

“You got kids who are going to take it with them for the rest of their life. And the best combination is grandparents bringing out grandchildren,” she said. “It's just stunning.”