Quite a few of Denver's actors and performers have a rare day job: They're the voices of the federal program that popularized talking books.

The city is home to two of the seven private studios around the country that record audiobooks for the National Library Service. The titles go out to an audience of more than 800,000 people who can't use printed books. Among some listeners, the narrators are celebrities.

You might think reading is an easy job.

That would change sometime in your third straight hour of saying words out loud.

Each time you mess up a phrase, or a pronunciation, or an accent, your helpful colleague the producer plays it right back for you.

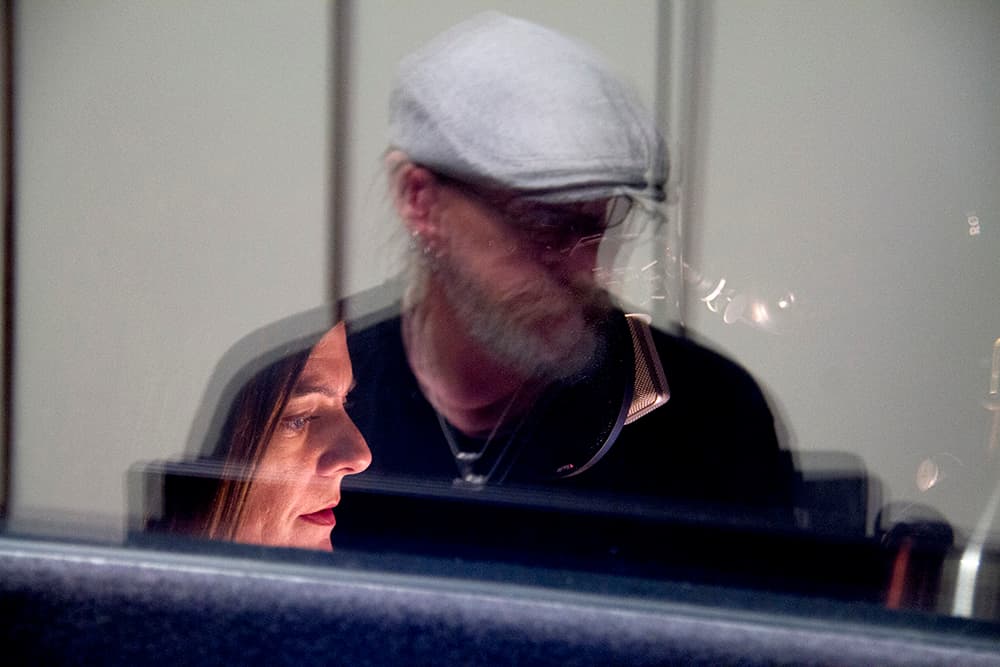

"It's quite humbling," says Mare Trevathan, settling in for a Monday afternoon recording session at Books To Life.

This was her 300th book — the legal drama Corrupted. Two nights earlier, she was playing a badass abbess at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival. A lot of the same skills come into play, but it's not the same game. Even Shakespeare's longest works can't compare to the sheer number of words an actor might deliver from your typical novel.

Almost everything the listener hears comes from the narrator's first take.

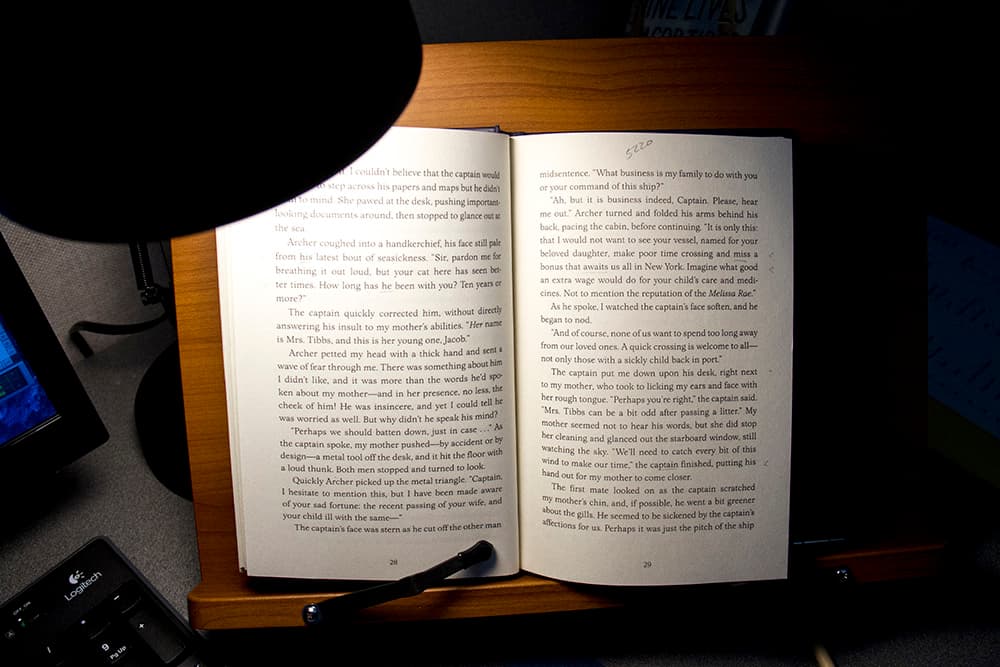

A research team reads ahead of the actor, preparing notes about pronunciations and other details. The narrator scrolls through those details on a tablet as they turn the pages of the book itself.

Otherwise, they're essentially acting out the script in real time.

There's no skimming ahead, no speeding through sections. Each bit of punctuation is an instruction, each quotation mark a shift in tone. Trevathan subtly acts out the lines, her hands dancing from side to side as she reads by the light of a single lamp.

"After a while, you do enter a sort of natural rhythm of sorts, or yeah, a meditative state," says Jack Bouchard, Trevathan's monitor for the day.

I watch them record, and they do lock into sync — sometimes Trevathan only needs to say "errrr," before Bouchard is rewinding her back to the exact spot she wants.

"It's a weird kind of mind meld," the actor says.

People have been listening to audiobooks for more than 80 years, and this service made some of the first.

The U.S. Congress created the National Library Service, part of the Library of Congress, in 1931. Within two years, about 5,000 talking-book machines were on order for 17 different states.

At first, a single book might come on 10 or more special records, before the transition to cassettes. The U.S. program never adopted CDs but shifted in the last couple years to a digital device that can play audiobooks from the internet. (The devices are also designed for use by quadriplegic people and others with significant physical disabilities.)

Today, the $50 million program has about 150,000 audiobooks and publishes 58 audio magazines, plus 68,000 titles in braille. Its content goes to an audience of more than 800,000, all of whom are limited in their ability to see printed text or otherwise use a book.

The rise of digital audio has been a boon to the program – a significant portion of the narration is donated by commercial audiobook producers –but the service still relies heavily on studios and actors in Denver and around the country.

Through the years, NLS narrators have developed a particular style.

"The Library (of Congress) has always wanted to keep these things more narrative," Maxwell says, as compared to the elaborately produced, multi-actor productions starting to emerge from commercial services.

Over time, though, the style has loosened a bit.

"It went from people who just had fine voices, intoning words and reading like an announcer, to being more populated with actors," Trevathan says.

The goal, according to Maxwell: "Make it interesting and engaging, but you want to leave some room for the unsighted or handicapped listener to use their imagination."

And if you do it right, you become a niche celebrity.

Nine people record regularly at Books To Life, and more at Talking Books Publishers.

Some are actors, while others work for Colorado Public Radio. Jill Ferris, who in the 1950s was Denver's best-loved "weather girl," is a regular at Books To Life.

So, the narrators tend to live public lives already — but they enjoy a very particular kind of fame in the world of audiobooks.

"They're like movie stars," says Heidi Cluff, production manager for Books to Life. "Many listeners, they have their favorites. There's a lot of people — they grew up with it. It's their TV."