Twice a year for 63 years, the Denver Randall's and the Omaha Merchants have faced off in a softball grudge match.

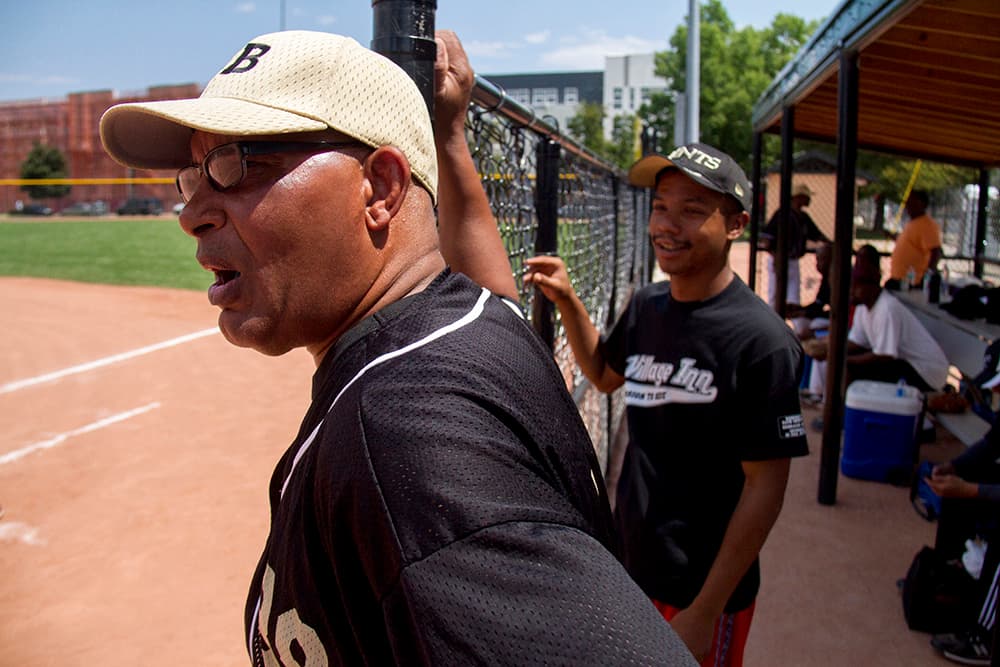

To the players rounding bases inside Five Points' Sonny Lawson Park on a hot July Saturday, there might as well have been a roaring audience on the sidelines where 12-foot bleachers once towered over Park Avenue. But passers-by might hardly have noticed this quiet celebration of an enduring relationship between the two cities and a legacy of ballgames in a neighborhood as old as the city itself.

It started in Omaha in the late 40s.

Joe Brooks and Louie Lewis Arterberry were more than best friends. Brooks was first baseman to Arterberry on the mound. They were tight, competitive and took fastpitch softball very, very seriously. They played both baseball and softball, dabbled in the semi-pros and, according to folks who knew them, were inducted into the Nebraska Softball Hall of Fame. (The only such organization that exists today has no record of them.)

Though a thorough Google search won't reveal anything about either Brooks or Arterberry, they would become legends to the amateur softball players who followed in their footsteps.

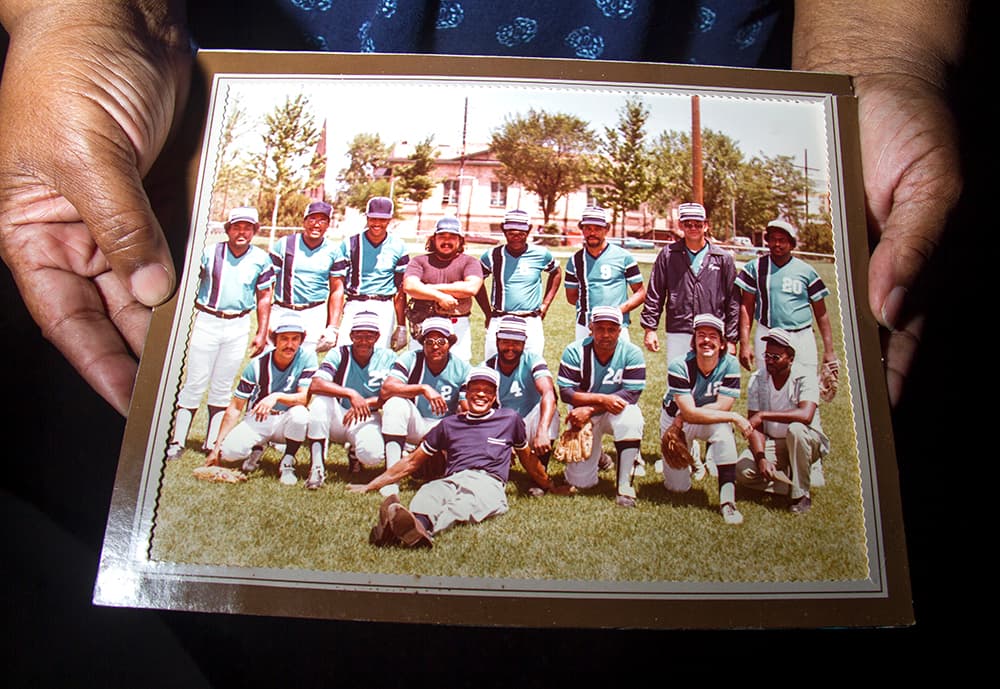

According to Kenny Moore, Arterberry’s nephew, the duo played on a traveling team based on Omaha’s north side called Young’s Mobile, named for the neighborhood service station that sponsored them. In 1953, Brooks moved to Denver where he started the Cloud 7 softball team at Sonny Lawson Park. He called up his old friend Arterberry in Omaha and laid down a friendly challenge that would inspire the semi-annual bouts that have continued for over half a century.

When he arrived in Denver, Brooks' Cloud 7 was the new team on the block. They would compete against Jetset, the hometown amateur team, before merging to form the mighty 34th Street Merchants. They'd tour the country taking on teams in places like Yuma and Ruby City. And were they ever fierce!

Beverly Buckmon, for whom Brooks was like an uncle, said the team was ejected by umpires during a Glenwood Springs tournament for being too talented.

"They had hit too many home runs," she said. The umpire "said they were too good to be in the tournament."

The 34th Street Merchants' home games became a community locus in baseball-crazed Five Points.

"Oh, it was every weekend. We just had a ball," reminisced Buckmon, who herself used to play on the league's ladies team on the mound, at first base and in the outfield.

Other players recalled packed streets, concessionaires, buses full of athletes and fans unloading on California Street. As time went on, pomp and circumstance faded and names changed -- the 34th Street Merchants eventually became the Randall's, named for a nearby bar.

Denver has always been a ballgame kind of town and Five Points a ballgame kind of neighborhood, says Jay Sanford, Denver’s preeminent baseball historian. Sonny Lawson Park was built in 1888, and "it's never been anything but a baseball field," he said.

As the seat of African-American culture in the city, Five Points was the center of Negro League baseball in earlier years and hosted teams like the Colorado Black Diamonds and the Denver White Elephants.

Now, it's important to note here that the 34th Street Merchants were never segregated. While teams in the old Negro League laid the groundwork for the Merchants in Five Points, an ambitious event in Denver helped reshape baseball culture across the whole country and made it possible for future Five Points teams to compete on an even playing field.

Denver was always an "open town," said Sanford, a place where segregation was less severe. There were definitely problems, he said, but Denver was seen as an exception when compared to other cities.

In 1934, the Denver Post Tournament, which aspired to be something of a Minor League World Series, brought teams from all corners of the continent together for what was the first integrated baseball tournament in U.S. history. After that, said Sanford, teams went back home to Texas or Kansas or wherever and brought with them exposure to integration and a cultural shift.

"Jackie," Sanford said, meaning Robinson, "would not have integrated in ‘37 if not for the Post in ‘34."

So when Brooks and Arterberry finally got around to starting their enduring game in ‘53, they were not playing in a cultural vacuum.

Even still, the Sonny Lawson field itself reflected an uneven status in civic life.

"It was raggedier than a 13-dollar bill."

That's how Joe Stukes, a longtime player who watched from the dugout, described the past field conditions.

Over the last five years, Five Points residents have seen not only an enormous transformation of their neighborhood but also of the historic ballfield. Across Welton Street today you'll see the nearly-completed shells of new condos over the nicely manicured outfield lawn and new fencing that encloses the park.

Stukes sees the improvements and the new gates, which get locked at night, as an unwelcome barrier between the neighborhood and its rightful field.

Others are glad to see the park cleaned up.

"It never looked like this," said Dave "Big D" Gallegos, who grew up around the corner and has been pitching on this mound for more than 50 years. "This should've been the first to be fixed up," he said, "and it was the last one."

But while the legacy left by Brooks and Arterberry on this hallowed block was certainly visible last Saturday, the burdens of history weren't exactly weighing on the minds of players or fans. Instead they were overcome by the excitement of a double play, kicked-up dust and pop flies.

The rivalry, for which there is no trophy, is really all about community. It's a family stitched together by red laces and many, many years together.