Three months ago, the city of Denver announced that it would temporarily ban people from parks where cops saw them using or selling drugs. Staff at the time described the policy as a response to frequent drug use along Cherry Creek, which the city called a "a hub for drug sales and use."

Police have issued 36 bans since then, but Cherry Creek hasn't turned out to be the focus. Instead, most have happened in Commons Park.

The city may finally have killed "Stoner Hill," the gathering spot for homeless hippies -- some of whom have moved on to the park next door -- with the new enforcement approach.

"It's to attack people who are of age smoking weed, which is not what the ban was intended for. It’s intended for heroin and drug use on the Cherry Creek path," said Eric Jackson, a regular on Stoner Hill.

To be clear, the city never said the policy was only for hard drugs. The bans are meant "for any illegal drug activity," which includes public marijuana use and open possession, said parks spokeswoman Cyndi Karvaski. "It’s for the entire parks system."

Jackson said the policy has been effective in uprooting the young and largely homeless crowd that has gathered at Commons Park for years. "I sat out there probably three weeks daily, from 11 until 5:30, and no traffic," he said. "I’m sure those homeowners are looking down and smiling - but I like human beings in the park."

Don Cohen, president of the Riverfront Park Association, also said that an enforcement push has moved people to nearby Cuernavaca Park. In his view, that gives some reprieve for other Commons Park users from the smell of marijuana, occasional fights, cursing and panhandling.

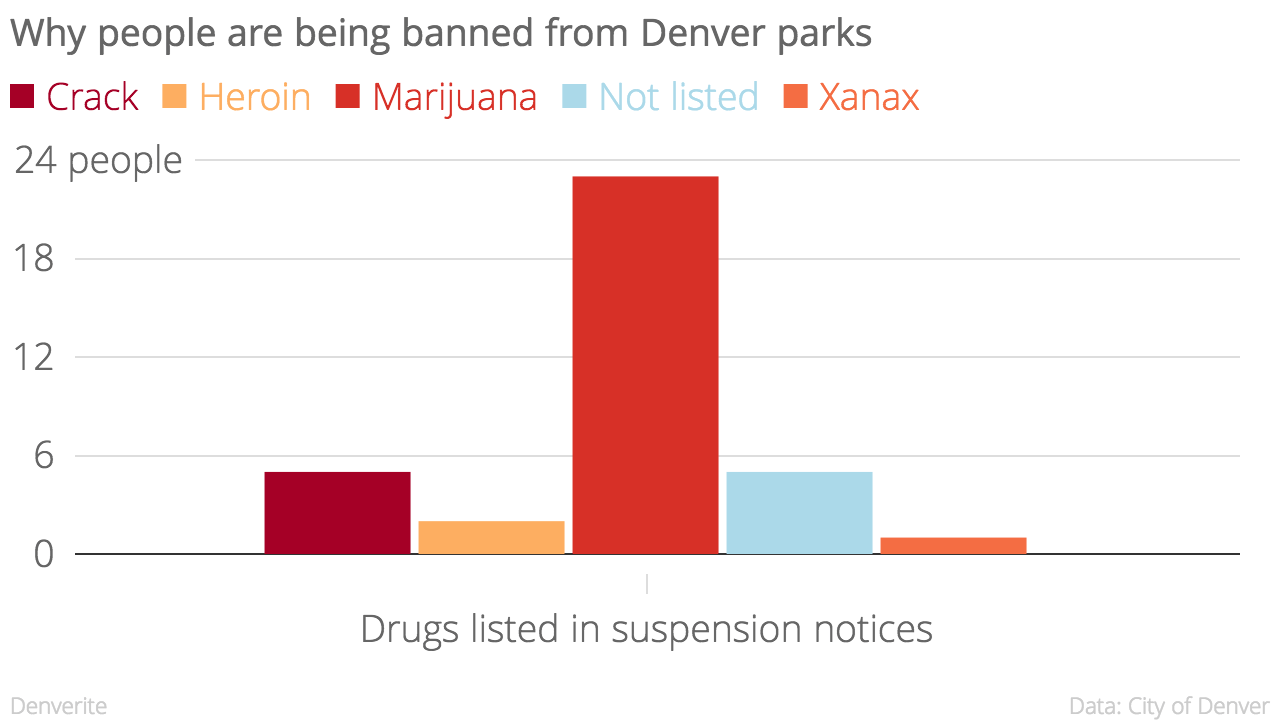

As the chart above shows, 23 out of the 36 bans have been for suspected marijuana use or possession.

Most people also were ticketed or arrested when they were banned. A few are accused of selling drugs, but for the most part they allegedly were seen smoking or holding marijuana. One man told police that he was only hoping to "smoke a bowl and eat a sandwich" in Civic Center Park.

Those who disobey the bans can be charged a fine of up to $999 or jailed for up to a year. The vast majority of those banned are listed as "transient."

Stoner Hill has been the target of most of the bans.

Police for the first couple weeks deployed the new policy mostly in Sonny Lawson Park to drive out alleged crack-cocaine users. Since Sept. 20, though, 19 out of 24 bans have been issued in Commons Park.

"They literally cleared out [Stoner Hill] in a matter of a week – because five people who were all friends got banned, and one or two of them were those you could trust to watch your bags," Jackson said.

The bans, Jackson said, have instead driven the stoner group to Cuernavaca Park, just down the South Platte River, where they now gather in front of the Flour Mill Lofts. While the hilltop crowd was somewhat hidden out of sight – unless you decided to walk up there – the new spot is directly along the bike path, for better or for worse.

The suspensions often have been given by undercover officers, or by uniformed officers who are working "off-duty" hours paid for by the Riverfront Park Association. The RPA previously convinced city staff to erect a fence around the park to keep "urban travelers" away, and later funded security cameras that police use to monitor the place.

In this case, though, the RPA says it did not ask police to start using the ban policy in Commons Park. "The city clearly is aware of our residents' concerns and, on their own timeline and volition, chose to address it in their own way," Cohen wrote in an email.

Most people seem to be obeying the new policy so far.

So far, only three people have been caught violating the ban. The city is also claiming some degree of victory along Cherry Creek, where Karvaski reports an apparent reduction in drug use.

Critics like the American Civil Liberties Union say their deeper concern about the policy is that it's an effective way to shuffle homeless people out of public areas. The ACLU has called it an "end run around the Constitution" because people can be banned immediately by police officers, with the option to appeal later.

In five cases, officers didn't list what drugs they were accusing the person of using. In one case, a 59-year-old homeless man was temporarily banned from Lincoln-La Alma park because he had "needles that are used for drugs," had ingested an "unknown substance" and is a "known drug user," according to the issuing officer.

The bigger question may be whether the city keeps the policy, which will expire late in February if it's not renewed by parks director Happy Haynes. The ACLU is not saying just yet whether it will challenge the policy in court.