Most people think of the Denver Botanic Gardens merely as a pretty weekend activity. While that's true, there's more to it beneath the surface, in this case, literally.

Take a flight of stairs down below DBG's greenhouse and you'll find the herbarium, a massive library of pressed plants collected over the course of a century. And most of the archive's accessions, or entries, have been collected in Colorado.

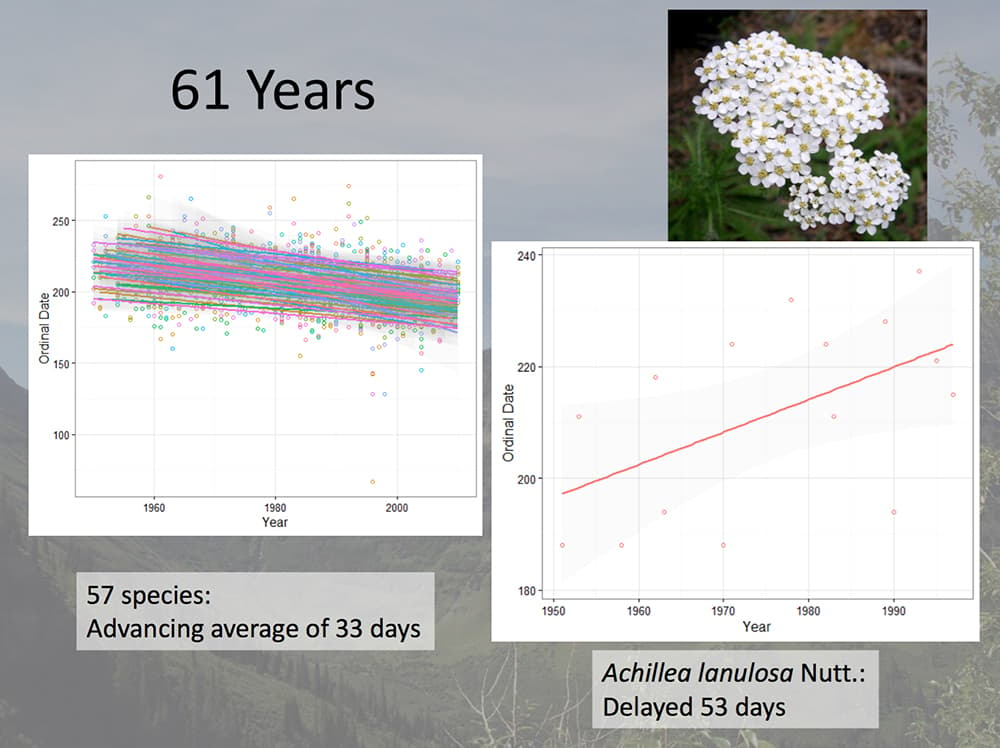

Using the data associated with these pressed accessions, a team of scientists working at the Gardens were able to show how plant life cycles have shifted since the 1950s.

Qualitative ecologist Michelle DePrenger-Levin, conservation botanist Rebecca Huft, database associate Richard Levy and systematist Melissa Islam collaborated on a study that, according to Huft, shows a number of Colorado's alpine plants have bloomed earlier and earlier over the last 60 years.

Each plant in the collection is noted with a collection date which points to the time of year that it bloomed. Stacking all these various collection dates together reveals a pattern of change.

"The most surprising result," Huft told Denverite, is that "the changes are strong enough to still show a significant trend toward earlier flowering times when all species are analyzed together."

According to their data-crunching, an average of 57 species bloomed an average of 33 days earlier today than they did in 1955. This change in life cycle, or phenology, is an indication of changing climate in Colorado.

While Huft says they can't say for sure if globally-rising temperatures are the culprit, she says "these results provide strong support for plant changes in response to climate change."

The study also helps to identify species to keep an eye on in the future.

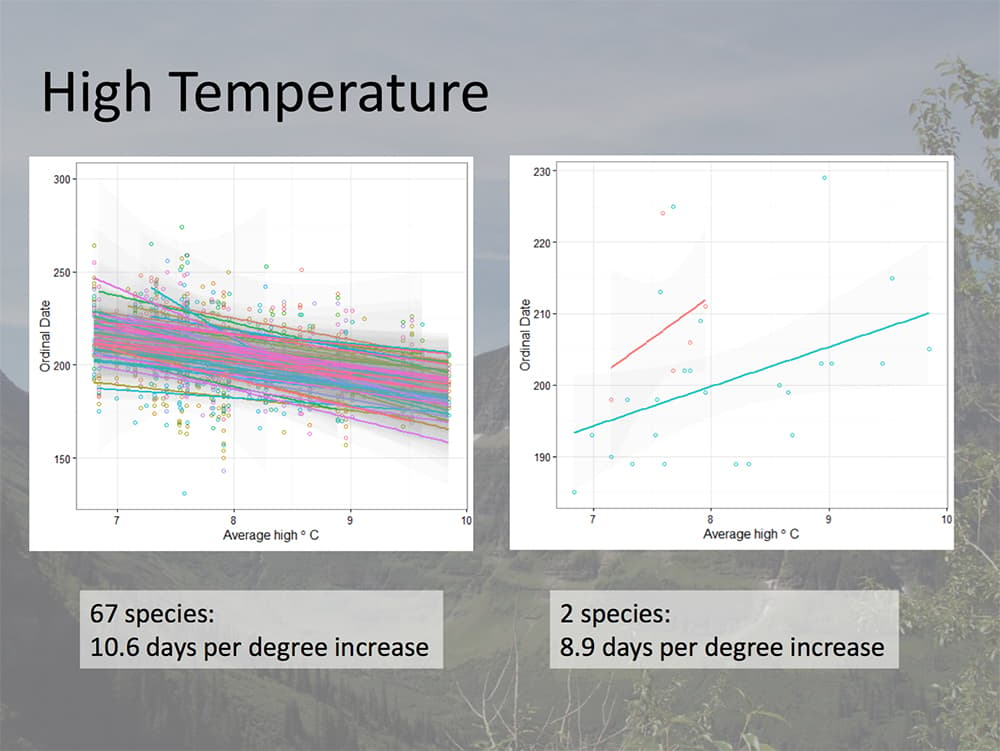

Overall, the team concluded that all 468 species' bloom times advanced an average 3.4 days per degree that average high temperatures increased. Of those species studied, 67 showed an average 10.6-day increase per degree.

Not all of the species show earlier bloom times, said Huft, but while some plants are blooming sooner due to higher average temperatures others are changing their range, moving higher up mountainsides, or else becoming less dense in other areas.

The study is set to be published this summer. Findings were presented in October at the Natural Areas Conference in Davis, California. The charts on this page come from a powerpoint presented at the conference.

While the Denver Botanic Gardens' study pulls data from all over the state, Colorado is also home to a plot that's been observed since 1973. Dr. David Inouye has kept up continuous monitoring of plant and animal life cycles at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Gothic that's become the gold standard for such research.

In a 2009 analysis of four species over 39 years, Inouye and his team found that "plants are leafing out and flowering earlier in many locations as a response to warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt."

Because this study worked with live plants, the research team could also see beyond first bloom times to other effects that point to a changing environment. "Climate change," says the study, "is also influencing the reproduction, growth and other important traits of many species."

It's proof that foresight is crucial to effective science. The Botanic Gardens' study was only made possible through the diligent collections made by naturalists that began more than 100 years ago. In fact, the herbarium contains plants going back as far as 1821, though the very old accessions tend not to come from Colorado.

The herbarium itself predates the Botanic Gardens, founded by George Kelly and Kathryn Kalmbach in 1947. According to Melissa Islam, the current head curator, Kalmbach was the first to manage the collection until she died in 1962.

The library has since been named the "Kathryn Kalmbach Herbarium" in her honor. It contains about 60,000 specimens and adds about 1,700 each year.

And you too can feast your eyes on the collection. Islam says curious parties are "welcome to visit Monday-Thursday, 9 to 2 p.m. We encourage visitors to make an appointment." To do that, you can call 720-865-3593 or email [email protected]."

You can also participate in ongoing phenological studies through Nature's Notebook, a citizen science program that tracks plant stages and played a part in DGB's study. All you need to do is sign up and then take simple notes while you're out enjoying the Colorado wilderness.