Ansel Adams worked constantly, 18 hours a day for seven days a week, building a huge following while he crisscrossed the nation. A handful of those images -- like Moon Over Half Dome -- became part of our collective conception of the West, perhaps even driving some of the post-war surge of tourism to the national parks.

The late great's archive, though, goes deeper than I knew. He often shot here in our backyard, including several dozen along the Front Range and in Mesa Verde that were commissioned by the Department of Interior in 1941.

The photo mural project was halted the next year as World War II wore on, and hundreds of images were forgotten for decades in the National Archives, only to be published in 2010.

I stumbled across the online archive earlier this week. I was thrilled to see how the late great saw some of the same landscapes I've photographed -- and, well...

I was a little disappointed at first. A few of the first were, well, less than great -- or at least kind of passé.

But as I thumbed through the rest (OK, clicked through them), I started to realize why I was feeling underwhelmed: We are completely saturated with landscape photography. Everybody with a phone can get some real quality, and I think the result has been a race toward ultra-splashy, colorful landscapes.

I might have just scrolled past some of these on Instagram, honestly. So, I decided to spend a little longer with them.

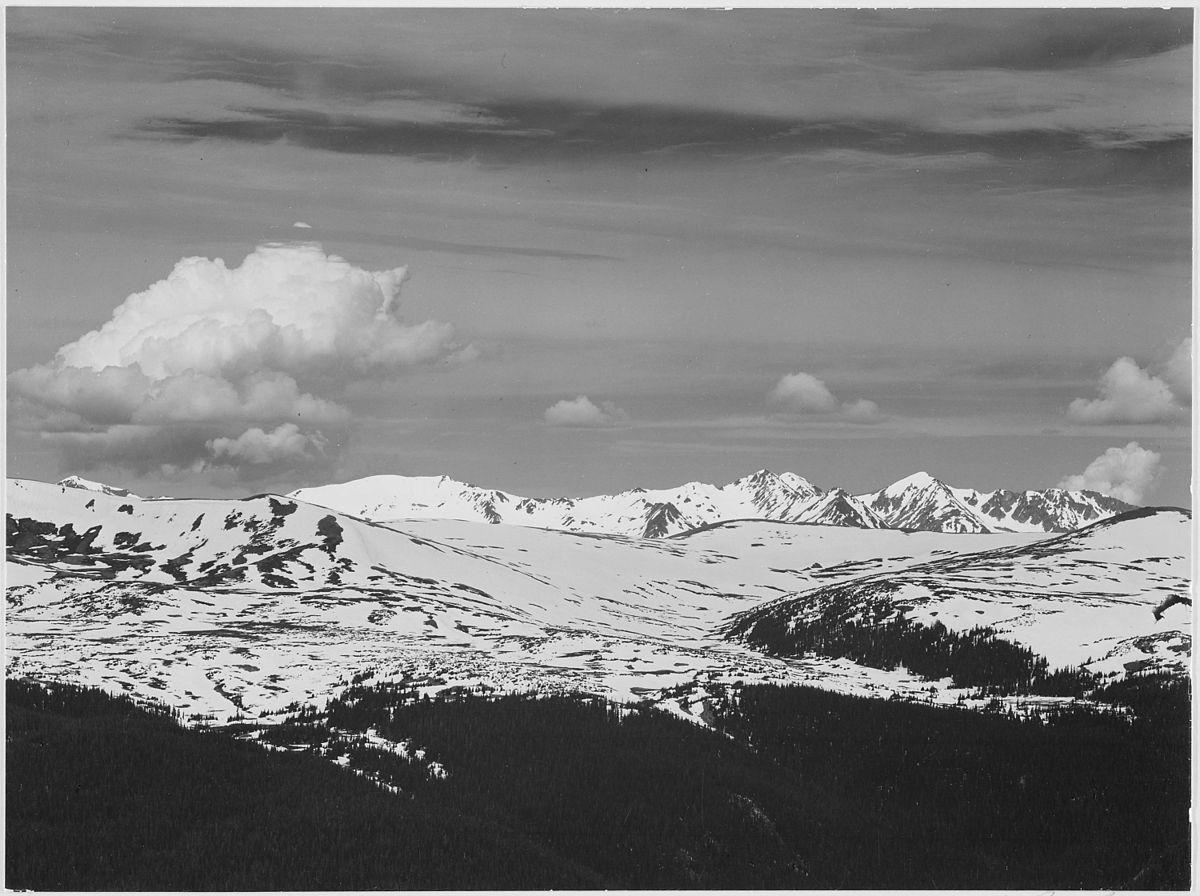

The one above, I think, is the most beautifully composed of the Colorado images I found. I love how the sharp lines of the mountains literally fade into the clouds, which themselves have these layers of light which almost don't make sense -- and then the black nothing above. The mountains somehow seem bigger and smaller for the amount of sky above them.

This one kind of made me recoil at first. The foreground is so stark, almost like it's been Xeroxed (Ed. note: Xerox is a company name that commonly refers to a machine that people in the before-times used to make copies of pieces of paper.) -- but that contrast also pulls out the details of the snow and the glades clinging to the mountain. Look at those tiny little trees mid-frame -- and then, slowly, your eye finds the more finely toned background.

This also got me to thinking: Why is the guy so famous? I mean, couldn't anyone with enough time shoot good landscapes? They're not going anywhere...

In fairness, Adams shot some lovely and historically significant portraits. But part of his success also came from sheer persistence. He not only spent weeks in the field, but intentionally cultivated both commercial contracts and communities for art, as the New York Times' Lens blog described it.

Anyway, I'm also a fan of this one -- despite some weird light on the left -- for the way it portrays the scale of Longs. Look how it looms up there, and how far away it seems from these wimpy little trees, and the way the shadows turn the forest into rock.

I also figured we should give him another chance with Mesa Verde. This one is just a nice shot, and a great case for black and white: every shade of grey, and so much age in the texture.

This has been just a small sampling of his work here, of course. You can browse the public-domain archive of his Department of Interior work here.

There are also his more-famous images of Colorado, which are still locked behind restrictive publishing licenses. See those for yourself here: The Dolores River. Maroon Bells. Independence Pass. Silverton. Spanish Peaks.