The way to Loch Vale in the summer is not the same as it is covered in snow. Leave the parking lot at Glacier Gorge in Rocky Mountain National Park, strap on your $5 snowshoes and head southeast.

Follow the winter trail through the woods until you hit what Dr. Jill Baron calls the “Wall of Denial,” an intimidating frozen waterfall. Brave that, and you’ll reach your prize.

Baron knows this hike better than anyone. In 1986 she founded what became the longest-running environmental monitoring project in Rocky’s history, and she says she’s gotten to know the watershed like it was her own kid.

And her kid just had a birthday.

Rocky Mountain National Park was founded 102 years ago this week. Back then Denver was a youthful 40. Capitol Hill was still considered the edge of town. Civic Center Park had yet to be built.

But even then, growing Denver and the surrounding communities had already made a profound impression in Rocky Mountain National Park's soil.

In fact, the story of Denver's very establishment can be found embedded in the park, and Baron can see it.

Baron is a United States Geological Survey field ecologist who works at Colorado State University. She's known for setting up Rocky's longest-running monitoring sites that keep tabs on air and water pollution in this otherwise pristine landscape. Baron discovered that nitrogen was tainting the park's high lakes, and she was the first to realize it was being whisked up by wind from farms and cars on the Front Range.

She and her team found the stuff by extracting long cylinders of dirt from lakebed in the park. It turns out those lakes are pretty placid, so sediment stacks up neatly in layers over time. When she studied the lakebed cores, Baron could see the history of air pollution from the burgeoning Front Range below, both expressed in minute amounts of nitrogen and lead. The faint and ever-fluctuating pollution levels reveal a timeline of Colorado history, like an imprint in the sand.

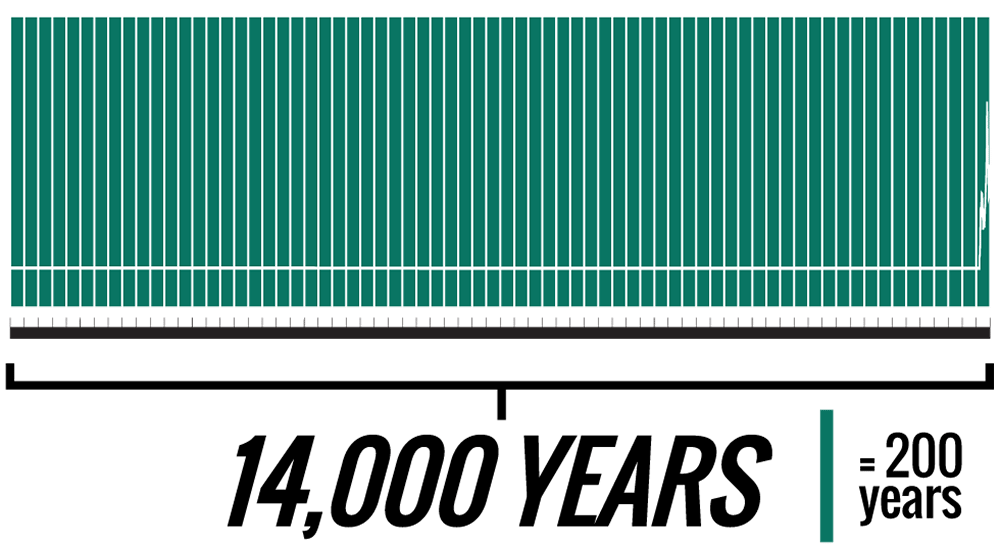

Her team’s analysis of the sediment shows 14,000 years of undisturbed chemistry in the lakes that was abruptly altered with signals of lead in 1860 by the arrival of white settlers and the Colorado Gold Rush.

That’s right. The arrival of European settlers is recorded in Colorado’s alpine lakes.

Lead pollution shoots up from there, falling a bit during the Great Depression before peaking in the first half of the 20th century. It fades from Rocky Mountain National Park as unleaded gasoline became the norm in American society.

In the second half of the 20th Century a new signal started to rise: remains of algae that show how nitrogen began to fall over the park. Baron says this is directly related to a population boom on the Front Range after World War II. That unprecedented influx of people prompted the arrival of more cars on the road and an explosion of feed lots from Denver to Fort Collins that used synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

"All of that is contained in these lake sediment cores," Baron said, "and we can see it."

Today, if you know where to look, you’ll find a cluster of monitors above the Loch that have been updating this atmospheric history since Baron set up shop in the 80s. These days, she says, the story that the data tells is one of a smarter society. She’s seen nitrogen levels fall in spite of the new population boom we’ve witnessed in the last decade or so that has, she says, “everything to do with new technologies for energy production.”

The switch from coal to natural gas, as well as more efficient vehicles, has resulted in a cleaner outlook for places like Rocky Mountain National Park, and that’s good news for everyone who has a soft spot for wilderness like this.

Baron and her team will keep hiking each week to Loch Vale as long as they can keep their study going, continuing to learn what this seemingly pristine landscape can tell us about our lives 4,000 feet below.