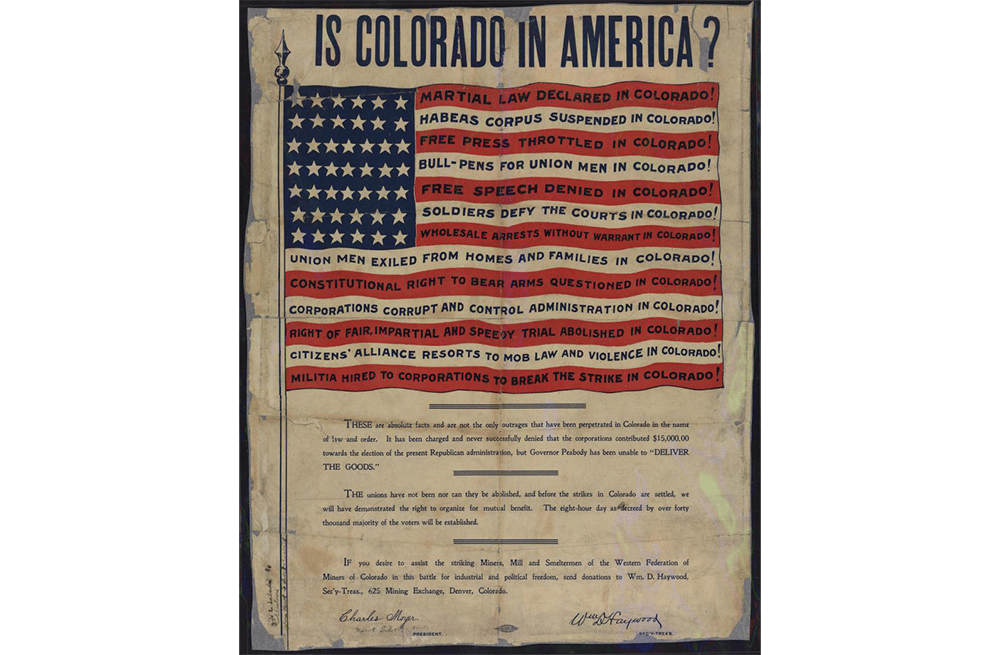

This poster got the man who made it arrested for flag desecration, and the ensuing court cases only affirmed the power of Colorado's governor, James Peabody, to enforce martial law, exile miners from their homes, detain people without charges and do all the other things that led union activists to wonder, in 1904, if they were actually living in the United States.

It's part of a huge online collection of radical political posters from American history, the University of Michigan's Joseph A. Labadie Collection. Other versions of it can be found online in the Denver Public Library's Western History digital collection.

The Colorado Labor Wars of 1903 and 1904 came after nearly a decade of violent confrontations between the militant Western Federation of Miners and mine owners and their allies in government and business. In his book Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, George Suggs says there was plenty of violence on both sides, but the complete intransigence of the mine owners when it came to negotiations only encouraged the radicalism of the unions. Gov. James Peabody came to power as an acknowledged representative of business interests who feared that volatile conditions in the mining communities were deterring investment from Eastern capital and endangering the economic security of the entire state.

He declared martial law and called out the National Guard to suppress the unions. He considered himself a defender of "law and order," but Suggs provides numerous examples of Peabody refusing to use the National Guard to stop violence coming from mine owners against union members. The power of the state ran one way. And the mine owners had even more say because they were the ones who financed the deployment of the National Guard.

Striking workers and union members were frequently "deported" from their communities, sometimes legally declared "vagrants" because they weren't working and subjected to mob violence from mine owners if they tried to return. Union members were also arrested en masse with no charges, and in communities where the unions were strong enough to have members holding elected office, those elected officials were turned out with no defense from the National Guard.

Things escalated even further when the federation called a sympathy strike of miners in support of smelters striking for an eight-hour day. Many of the miners already had an eight-hour day and a minimum wage of $3 a day, but the federation wanted to use the strike to deny ore to the smelters and break the power of employers. Peabody and business interests around the state perceived this as a grave threat to order and to the economy.

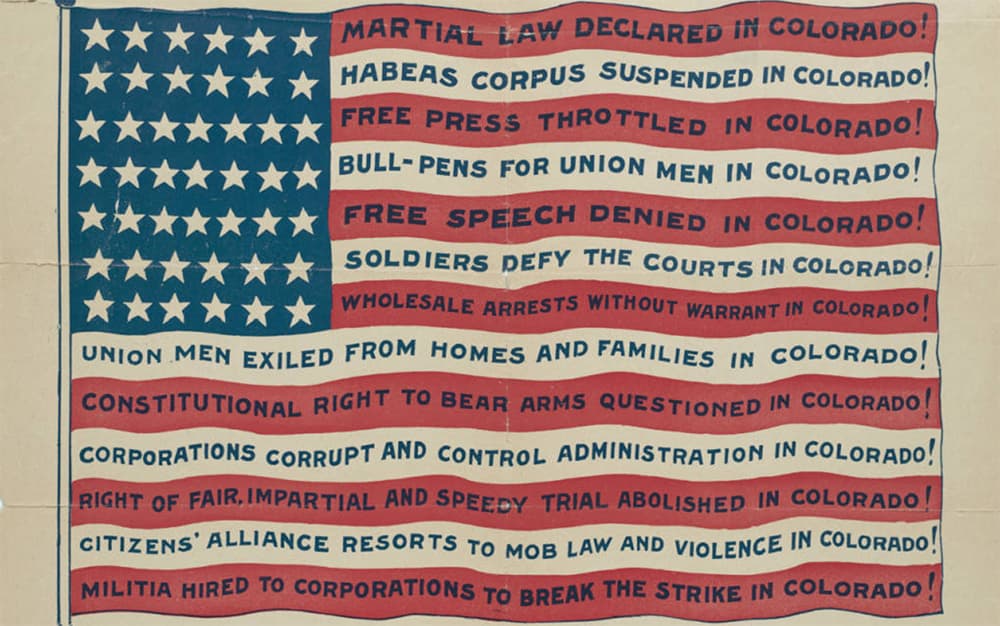

It was these conditions that prompted Western Federation of Miners President Charles Moyer and Secretary-Treasurer William "Big Bill" Haywood -- who would go on to found the anarchist union Industrial Workers of World -- to make the American flag posters with each stripe of the flag spelling out a different grievance under the title, "Is Colorado in America?"

- Martial law declared in Colorado!

- Habeas corpus suspended in Colorado!

- Free press throttled in Colorado!

- Bull-pens for union men in Colorado!

- Free speech denied in Colorado!

- Soldiers defy the courts in Colorado!

- Wholesale arrests without warrant in Colorado!

- Union men exiled from homes and families in Colorado!

- Constitutional right to bear arms questioned in Colorado!

- Corporations corrupt and control administration in Colorado!

- Right of fair, impartial and speedy trial abolished in Colorado!

- Citizens' alliance resorts to mob law and violence in Colorado!

- Militia hired to corporations to break the strike in Colorado!

A warrant was issued for Moyer's arrest on charges of flag desecration.

The agitation for his arrest started with a Denver newspaperwoman named Nell Anthony. This account comes from Bridget Burke in her essay "Is Colorado in America?" contained in the collection Colorado Labor Wars 1903-1904. Born on a plantation in Mississippi, Anthony made her living in sensational journalism under the name Polly Pry. She was fired from the Denver Post when she refused to retract a story that accused a union leader of advocating murder, and she started her own eponymous publication, Polly Pry. What began as a gossip rag spilling dirt on Denver's rich and famous soon was devoted almost entirely to anti-union stories. She urged patriotic societies in Denver to pursue a complaint of desecration, but it turned out that Colorado's law was not strong enough. It was legal to use the flag in advertisements.

Anthony's counterpart on the union side was another female journalist of Southern origin, Emma Langdon, who lived in the mining community of Victor. At one point, after the Victor Record published a story critical of the National Guard, the paper's printing force, including Langdon's husband, was arrested and held without charge. Langdon went to the offices at night and laid out and printed the paper by herself, then delivered it. Langdon was an active union member and experienced journeyman printer in her own right, but stories played up the loyal wife angle to show the depth and breadth of union support.

Langdon asked what mattered more: the flag itself or the values it was supposed to represent?

"Is Colorado in America?" she wrote. "If you consult the map you will find it there. If you read the facts in this recent industrial struggle in the light of American history and traditions, you will find nothing to recall the memories of our country's youth. ... Desecration of the flag? Was it not the deeds done under it and not the truths inscribed upon it that constituted the desecration?

Though Moyer quickly posted $500 bond on the desecration charge, he was soon re-arrested out of "military necessity."

Lawyers for the union sued for his release, and a district court judge ordered that he be set free. Military authorities refused. The case went first to the Colorado Supreme Court, where union lawyers argued there was no actual broad-based civil unrest to justify the declaration of martial law, which would make all the actions that stemmed from that declaration illegal. After all, the courts were still functioning in the counties where the strike was occurring! The government in turn argued the governor had the authority to declare martial law, and union members had placed themselves outside the protection of the law with their violent acts. The government prevailed, but Peabody ordered Moyer's released when the union prepared to appeal to the federal courts. Perhaps he sensed that wasn't an issue to keep testing.

However, a legal technicality led to a related case going all the way to the United States Supreme Court, which again upheld the right of the governor to declare martial law.

The fallout from the crackdown on the miners ended with one of the weirder political footnotes in Colorado history: the day Colorado had three governors. Union members campaigned heavily for Democrat Alva Adams, who believed arbitration, not military intervention, was the way to deal with conflicts between workers and mine owners. Business interests continued to back Peabody. With the state still under military law, Democrats used the slogan, "Anybody but Peabody!" to broaden their appeal.

The election was a fiasco. There was widespread ballot-stuffing in Democratic Denver and widespread suppression of the votes of miners in the mountains. Adams prevailed on the vote count, but the Republican-led legislature convened an investigation of the vote. They sided -- shockingly! -- with Peabody, the Republican, but he was sworn in over Adams on the condition that he immediately resign and allow his lieutenant governor to take office.

By then, though, the power of the Western Federation of Miners was severely reduced. Public opinion turned strongly against the union when a professional terrorist hired by the union blew up a train station and killed 13 strikebreakers.