Bernard Hurley's got California cowboy style -- tall and mustachioed in a brown suede jacket, roughly embroidered jeans and a well-weathered Lexus, not to mention full-body tattooing that stops at his cuffs.

The 60-year-old's name has stayed out of the headlines here in Denver, but he's deeply embedded in the development crew behind the billion-dollar-plus redevelopment of River North. For decades, his firm has worked largely on the environmental damage that plagues other developers' acreage in this industrial area.

Slowly and surely, though, Hurley has been assembling the money and land for an ambitious and unusual project that could finally deliver the kind of dense, interconnected and green space that has eluded RiNo's redevelopment. His plan for "Hurley Place," the developer says, is the best-kept secret on the South Platte.

"We're trying to create a sense of place for Denver," he said. "Although there's some really nice places to go in Denver, there's no real destination points, and especially nothing that involves the river."

And he's ready to talk now because he has the backing of Lynd, a San Antonio real-estate conglomerate with a portfolio that spans 50 metros. With a powerful partner in line, Hurley Place could start construction as early as 2018, with a budget reaching $250 million if it fully builds out.

"We’ve got the development experience and expertise to execute on the development," said Sam Kasparek, a principal and founding partner for Lynd. Bernard Hurley, he added, is "not a developer, but he’s a great businessman and an incredible visionary. I think it’s something where vision can meet execution and together get a project done."

The plan:

For now, Chestnut Place is a collection of fenced-off lots, warehouses and a couple small residences, including one owned by RiNo artist-organizer Tracy Weil.

If all goes according to plan, Hurley Place would fill this strip with new towers up to 12 stories tall. The project could bring an estimated 200 residential units, 200,000 square feet of office space, a 200-room hotel, 60,000 square feet of retail and restaurants and three music venues, including an amphitheater with capacity for 1,400 people, all along a couple blocks of riverside Chestnut Place.

Just down the street, a distillery company is working to secure space on another owner's property for an "outdoor oasis" that also makes liquor, while still another developer plans to rehab a large warehouse on Chestnut. Hurley's most recent major project, the new Blue Moon Brewery, stands on the eastern corner of the block. He would like to buy the Welcome Inn too, but hasn't struck a deal yet.

Put together, Hurley imagines a "festival street" where people can easily walk between music venues and eateries -- a kind of connectivity that's lacking in a neighborhood that barely has sidewalks. He hopes one day that his area will be so widely packed that it could host a multi-venue music festival in the style of Austin's South by Southwest.

"We want to create this large playground, more or less, where everybody can enjoy it -- not just the people in RiNo but everybody in the Denver metro area," he said.

Yeah, but let's talk bigger:

Hurley's project would be one of the grandest in RiNo, potentially on par with the budget of the gleaming World Trade Center Denver towers planned just a quarter-mile to the southeast. Kasparek, of Lynd, is confident that there's money in the markets to fund something of this scale.

Pulling this off would be a huge coup for Hurley. He originally noticed Chestnut Place when he was called into the neighborhood to inspect Ironton Studios. Seeing that developers were circling the brownfields, he bought acreage in the neighborhood for his business, Family Environmental.

In the two decades since, he has grown not just his business but his property holdings. Hurley has paid $4.2 million over the last two decades for his six acres of land, which may prove a steal for a block at the heart of RiNo's developing network of paths, parks and transit. (A single acre of land just blocks away recently sold for nearly $4 million.)

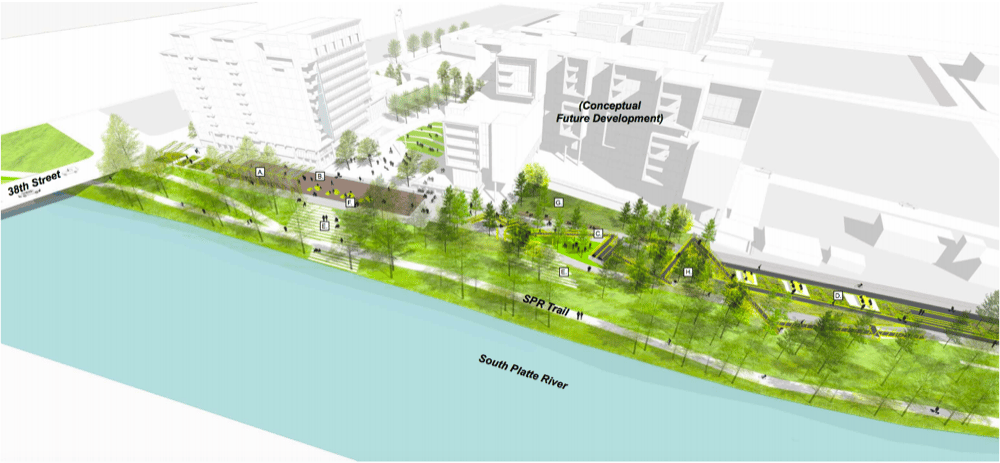

For one, Hurley's concept would slot smoothly into the city's own plans for new parks on the South Platte. Chestnut Place abuts directly on the land for the planned RiNo Park and the proposed but unfunded RiNo Promenade, a mile-long stretch of green space that may replace the existing street along the water.

Meanwhile, at the end of Chestnut, Zeppelin Development and its allies are preparing to build the neighborhood's first pedestrian bridge over the South Platte at 35th Street. District leaders also are planning to rebuild 35th Street itself, installing cycling tracks and planting trees along the weathered strip of pavement.

"As a neighborhood, the east and west side are really united in the idea that the river is an amenity, and we need to activate it and reclaim it," said Jamie Licko, president of the River North Art District.

"The festival street and the promenade and the park begin to create these really important gathering spaces that don’t really exist in RiNo. ... We’re creating new amenities, and I think that there’s synergy to be had in all of those spaces being kind of connected. They’re all going to have a little different vibe and a little different draw to them -- and that’s exactly what you want to do when you're trying to build a really healthy neighborhood."

Even bigger:

RiNo has long been called the hottest market in Denver, but the biggest changes are only just arriving: If these projects proceed -- and there's every indication they will -- we'll see a new urban area on the scale of Union Station, where some 20 blocks of residential and office have risen from an old rail-yard in the last 15 years.

"I think that there was an initial wave of development that took place. Now, some infrastructure's getting done -- the streets, the promenade design and funding," Hurley said.

At this point, nearly all of the property in the main district is spoken for and designed. All that's holding RiNo back from this new magnitude of development, he says, are the questions of timing and the markets.

Well -- that and a complicated but very important legal question.

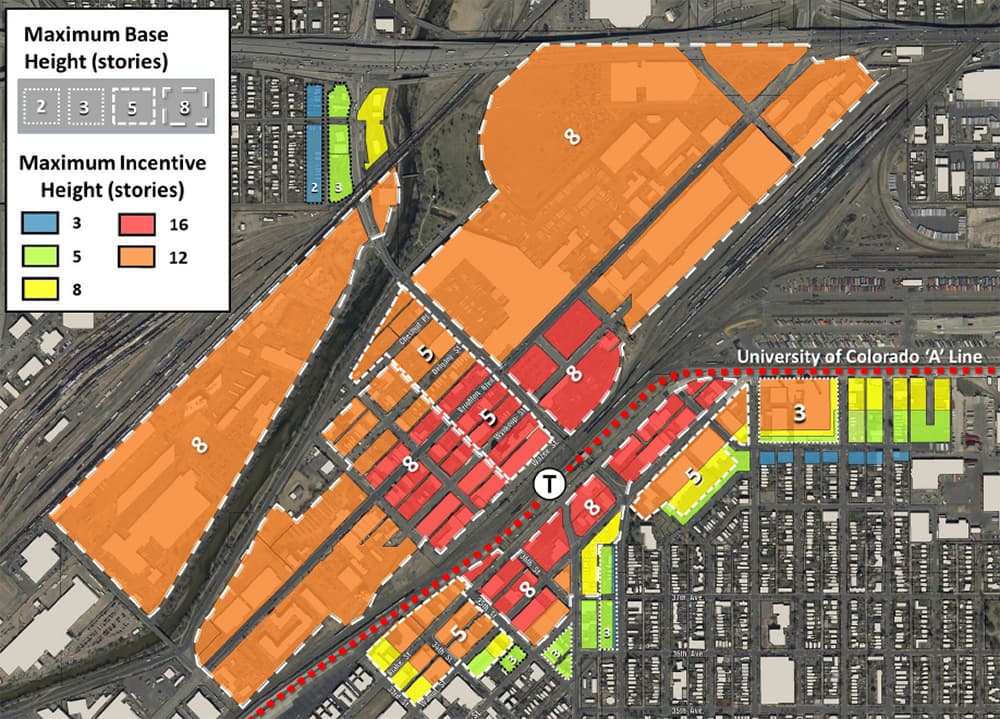

The city of Denver acknowledged years ago that this end of RiNo was going to be a development focus, and so the Denver City Council last year approved the idea that development near the 38th and Blake rail station could reach up to 16 stories.

That would allow 12-floor development closer to the South Platte -- including on Hurley's property. So, Hurley's and other's high-density plans seem to be kosher with the city -- but they're not home-free yet.

See, the city hasn't actually changed the zoning status that would allow development to those heights. The major delay is that the city wants to try out a novel affordable-housing policy in this area.

The idea is that developers won't be able to reach those maximum heights unless they actually include affordable residential units in their projects. In the rest of the city, developers pay money to fund affordable housing.

Hurley said he plans to take advantage of the affordability-for-height deal. "The whole theme of my development is all are welcome," he said. But his project (and some other big ones too) can't move ahead until the city works out the details of this new affordability arrangement.

It's not known yet how much affordable housing the city will require to go taller. A first draft of the deal might appear in about a month, according to Abe Barge, a project manager for the city.

From there, there could be another year of design work, according to Kasparek. That won't be too long for Hurley, who has been dreaming about his project for some 20 years, since he first noticed some half-forgotten property for sale along the South Platte.

He's building the project in honor of his parents, whom he credits for helping him buy his first property -- and he wants to hold onto that land when it's done.

"We're not selling any of this," he said. "I never did this, going in, to sell the property. I did it to leave a legacy for the city."