A 60-year-old making $30,000 in Mesa County could lose $8,000 a year of the federal money that helps people pay their insurance premiums, according to a new analysis of the Republican health-care proposal known as the American Health Care Act.

Here's why: Insurance costs for residents on Colorado's Western Slope and resort towns have for years been significantly higher than costs in the urban Front Range. The government has correspondingly provided more money to help pay insurance bills in those areas.

The Republican healthcare plans would effectively cut back the amount of supporting money available for people who live in high-cost areas, as well as for people with lower incomes, according to a nationwide analysis by Kaiser Family Foundation.

"This was a bill that was designed at the national level -- and what we see through this Kaiser analysis is the regional effects in Colorado would be negative for a lot of people," said Joe Hanel, a spokesman for the nonprofit Colorado Health Institute.

"What exists now isn’t great -- but according to this analysis, this would make it more expensive for people in Colorado’s high-cost areas to buy insurance even than it is today."

Wealthier people and people on the Front Range, meanwhile, could see a significant increase in how much government money they get for their premiums, depending on their circumstances.

The current Republican proposal radically changes how the government helps pay premiums.

Here's how it works right now: The country's current health insurance law, known as Obamacare, provides federal money to lower the cost of health insurance for consumers.

This money -- in the form of tax credits, technically -- generally goes straight to insurance companies, who then lower consumers' bills. Basically, the government pays part of your premiums, and that amount increases in areas where insurance costs more.

On the Western Slope, insurance costs more, so the government provides more money. More costs, more help -- which keeps out-of-pocket costs essentially identical across different areas, despite the higher actual costs, for people earning less than 300 percent of the federal poverty level.

The amount of help also depends on a person's income and age – more for poorer and older people.

The Republican plan largely gets rid of that method.

Instead, the AHCA gives out money largely based on age.

For example, every single 60-year-old in the United States who makes $75,000 or less would get $4,000 of annual help with insurance costs. Every 40-year-old in that income bracket would get $3,000.

Wealthier people and people in low-cost areas, meanwhile, would get more benefits than they currently do.

For example, a 27-year-old making $75,000 a year in Denver currently gets zero taxpayer assistance with her premiums, largely because young people in urban areas have some of the lowest insurance costs in the country.

Under the Republican plan, that young, high-income person would get $2,000 in tax credits in 2020.

Meanwhile, our 60-year-old making $30,000 in Mesa County would see their credits slashed from $12,450 per year to $4,000 per year -- the standard for that age bracket. Unless there's a drastic change in the insurance markets, that means they'll be paying a lot more out of pocket than the young person in Denver.

These effects aren't purely based on geography, either.

Across the map, poor people and older people would see their assistance cut.

"And that intuitively makes sense," Hanel said, "because when you go through maybe a progressive scheme, where people at the lower end of the income scheme get increased tax benefits, to a flat scale -- that will benefit people at the upper ends of the income scale and harm people at the lower end."

While the cuts would be more pronounced for lower incomes in western and rural areas, Kaiser's analyses found that any 60-year-old in Colorado making $40,000 or less would get less tax-credit help under the new analysis.

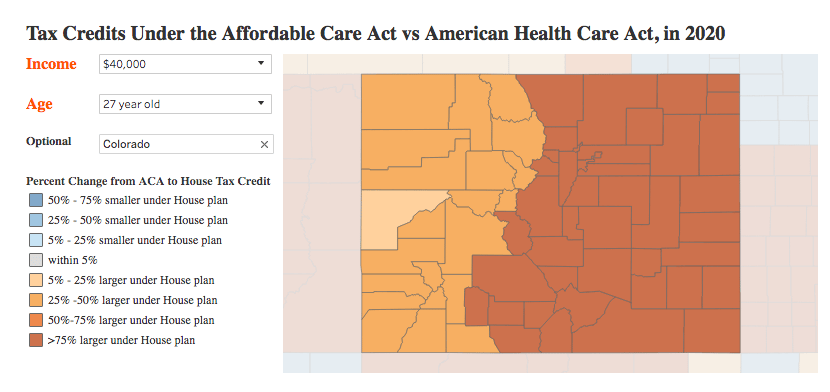

The cuts also become more widespread as you look at lower incomes. Any person in Colorado making $20,000, for example, would see less assistance under the Republican proposal. Here's what it looks like for 27-year-olds at the lowest income analyzed:

Conversely, all the 27-year-olds making $40,000 a year in Colorado would get more tax-credit support.

However, there are other factors to consider.

Tax credits are only one part of the current health insurance system. A group of experts writing for Vox examined the system as a whole and found that the average individual enrollee could see yearly costs increase by $2,409 per year in 2020.

The American Medical Association has described the Republican proposal as "critically flawed," warning that the change to the credits may "result in greater numbers of uninsured Americans."

Then there's Medicaid. After 2020, the federal government will no longer provide funding to add new people in the "expanded" category of Medicaid, which provides health care for low-income people.

"Basically the expansion population was child-less adults," Hanel said. Without the expansion, "they wouldn’t qualify for medicaid unless they were the very poorest of the poor." The AMA warns that this could result in low-income people losing coverage.

There's also concern, described in the Vox piece above, that the elimination of the individual mandate will disincentivize young, healthy people from buying insurance and "would likely lead disproportionately sicker individuals to enroll in coverage, driving up premiums."

Tholen, of the Colorado Hospitals Association, said that his group is still working to understand the full impact of the Republican proposal. A large part of the question will be timing, he said, pointing out that some components of the ACA weren't implemented until 2014, four years after it was passed.

"The hospitals really used that time to prepare for those changes and make strategic decisions," he said.

And the potential for change already is disrupting plans at St. Mary's Hospital in Grand Junction, according to Teri Cavanagh, a hospital spokeswoman.

"It took us two and a half years to get an approval through to build a new $50 million cardiovascular surgical center," she said. "If all of a sudden our business model were to change and our revenues to change and our way of operating were to change -- that may or may not be a good investment."