Globeville Landing Park is gone -- for now. The hilly acres on the South Platte River have been replaced by fenced-off mounds of dirt, dotted at times by workers wearing protective suits and respirators.

It's a striking sight, and it has inspired people to fly camera-toting drones over the park and to follow trucks on the 20-mile drive to the landfill where contaminated soil from beneath the park's surface is being disposed.

Needless to say, this ain't your average municipal project.

Globeville Landing, once an ignored little corner of the riverfront, now is at the heart of a huge fight over pollution, development and infrastructure in North Denver.

What's happening here is the first piece of an interlocking, $300 million series of projects that the city says will protect large parts of Denver from floods. Eventually, that protection will allow the widening of Interstate 70 through the city, a plan that has been the subject of intense community protest.

"That’s why it’s so dangerous -- it’s the first domino," said Christine O'Connor, a critic who has closely tracked the city's infrastructure plans for North Denver.

Construction at Globeville also will again expose buried garbage and potentially soil that was long ago contaminated by industrial smelters -- hence, the alarming sight of men in respirators. The city say it's following strict environmental protocols but its critics question the approval process, which we'll discuss later.

"We’re working hard to protect public health and the environment," said Celia Vanderloop, environmental project manager for the city's North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative

What exactly are they doing, and why?

When it rains, stormwater races down the hills, streets and pipes of northeast Denver toward the river. By nature and by design, this water runs toward Globeville Landing in its last sprint to the river.

Currently, a concrete culvert through the park carries water through the park. The current construction project would replace it with a combination for artificial creeks and underground pipes. The city says this will get rid of the ugly concrete canyon, freeing up parks space. It also will allow the outfall to handle the flows of water that the city's $300 million plan for flood control will put through it.

Much of the park and parts of the adjacent Denver Coliseum parking lot are being excavated as well. When it's done, the city also will rebuild the park at Globeville itself.

The larger Platte to Park Hill flood-control system also will include an open channel along 39th Avenue and a rebuild of City Park Golf Course.

The entire system will remove a large swath of North Denver from the path of 100-year floods -- including the Interstate 70 trench-and-cover project. The city's flood controls would save the state from having to build some of its own protections for the to-be-sunken highway. (CDOT will contribute part of the flood-control costs, and Denver says this project would be worthwhile even if it didn't benefit the highway.)

Lots of people hate the highway plan because it keeps a source of noise, disruption and air pollution in historically low-income neighborhoods. By proxy, this inspires resistance to the enabling flood-control projects. However, the current Globeville project also faces criticism for its own reasons, including the fact that it's once again resurfacing the contaminated materials of a Superfund site.

Contamination in Globeville:

The Globeville project runs through a contaminated Superfund site. Lead and arsenic have been found in particularly high levels in the area's soil, according to EPA documentation.

Globeville Landing is near the old site of the Omaha & Grant Smelter, which processed lead and other metals until 1903. Vanderloop said that early construction found asbestos in some of the soil at the Globeville construction site, too.

Excavation of the channel also will expose buried trash and associated odors from an old landfill. The city has installed sensors to monitor for contamination in the air for the next year or so, among other precautions, according to a plan filed with the Environmental Protection Agency.

Soil found to be clean will be stored for later use, according to Vanderloop. Soil found to be contaminated by asbestos is being put into trucks, wrapped in plastic and hauled to the Denver Arapahoe Disposal Site.

"We have done an extensive amount of environmental investigations. We’ve done a lot of planning and design review," Vanderloop said.

The construction crews will spray water, use ground coverings and plant new vegetation to minimize the spread of dust from the site.

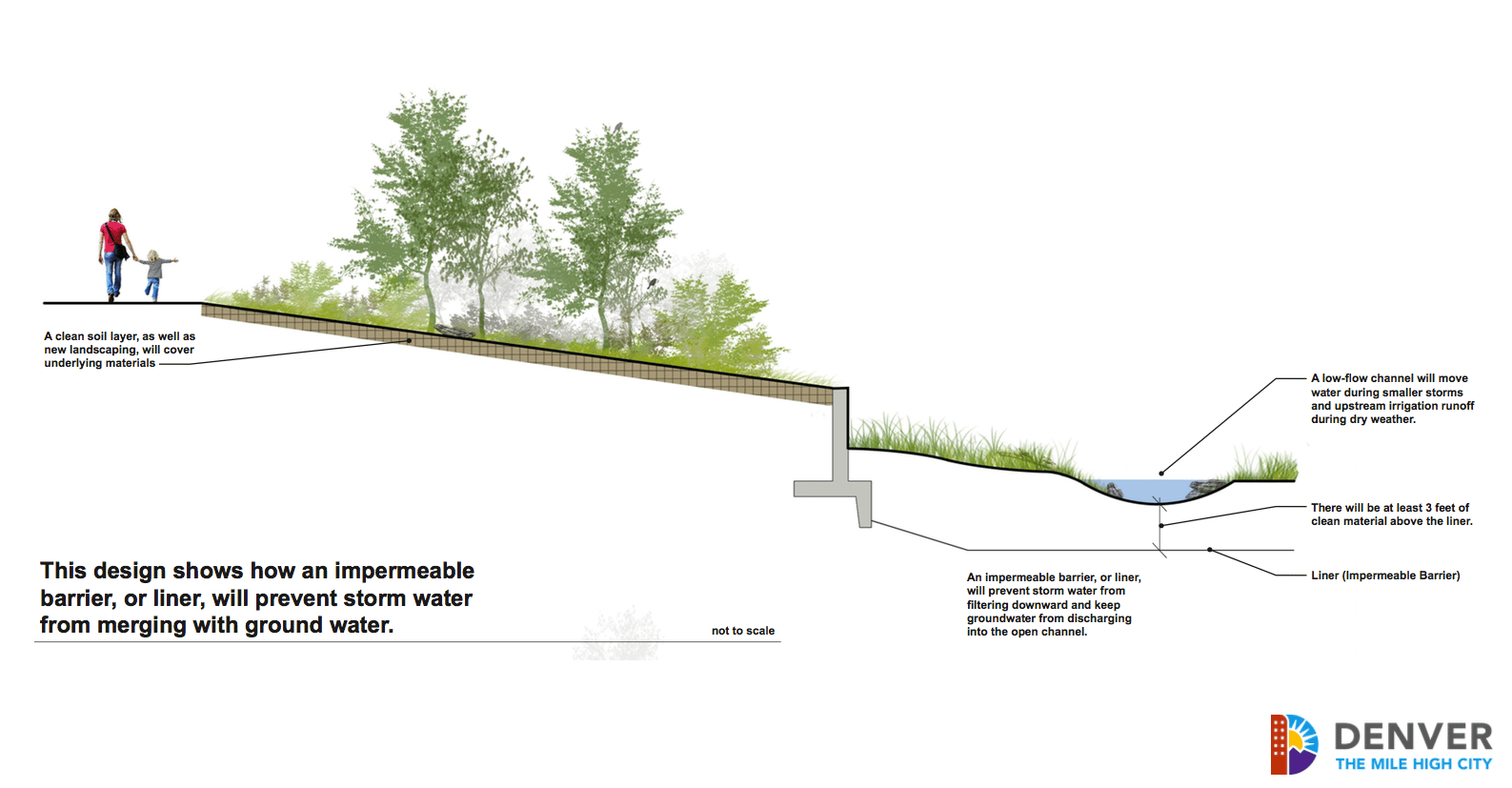

The channel itself is to have an "impermeable barrier system" to keep contaminated water from the ground from leaking into the stormwater, according to a design document approved by EPA. Aggregate stone columns will be sunk into the ground to anchor the channel, the document states.

Civil engineer Adrian Brown raised questions about the integrity of the outfall design in an article by Westword's Alan Prendergast. City staff countered his claims, arguing that he was working on faulty assumptions.

What about the park?

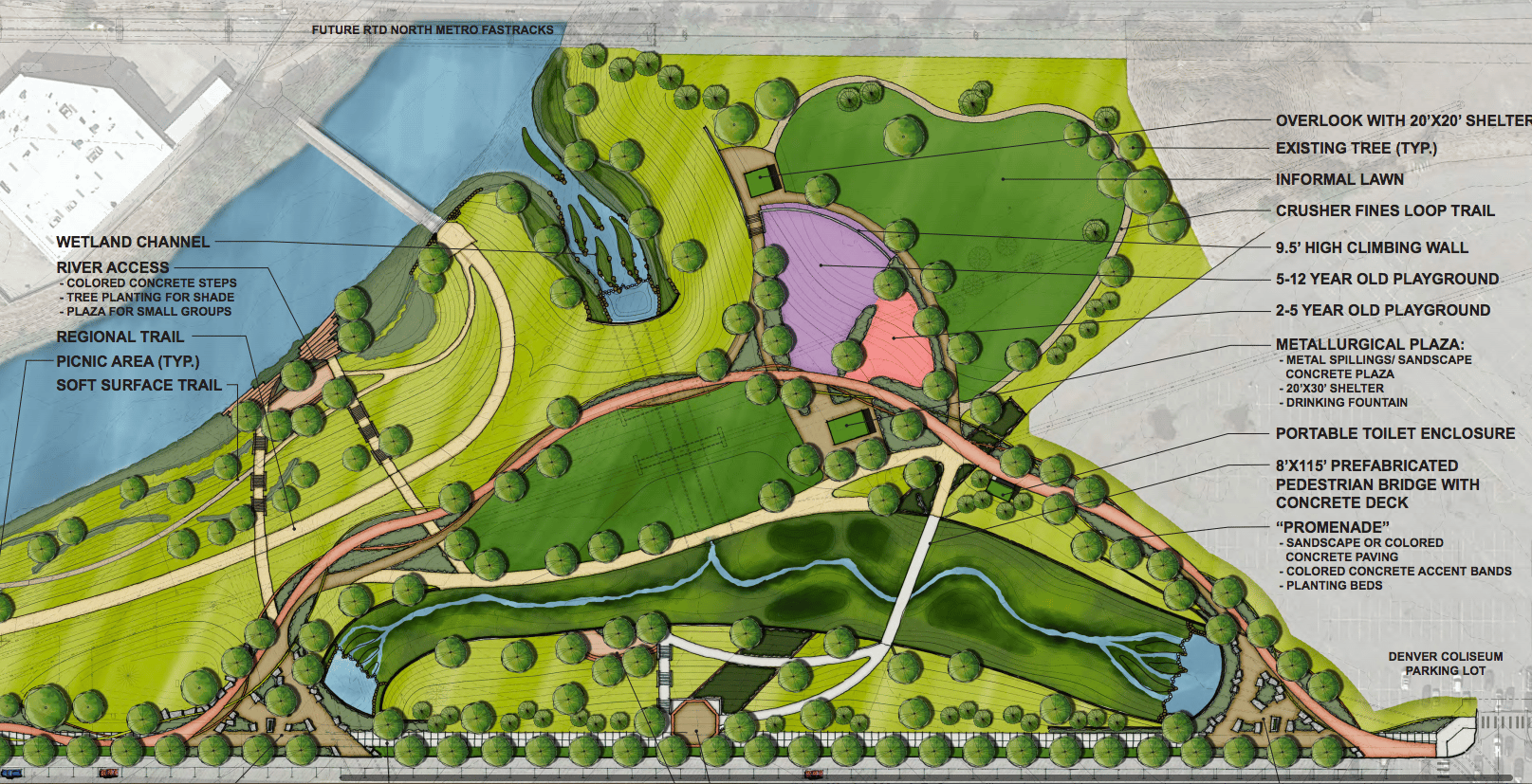

This infrastructure project will leave Globeville Landing Park looking much different. The pedestrian trail will be rebuilt wider, and there will be a new pedestrian bridge over the drainage channel.

The city also is working on a redesign of the park at Globeville itself, which will come after the drainage project. That project may include new playground areas, a climbing wall and picnic areas, according to Owen Snell of Denver Parks.

It's unclear whether there will still be a disc golf course at the park, but they're trying, Snell said. The regional bike and pedestrian pathway through the site should be open, if slightly rerouted, during the entire construction process.

When was all this announced?

Denver got EPA approval of its plan to work on the Superfund site back in July 2015 through a "time-critical" process. Later that year, in September, the EPA issued a public notice in The Denver Post. The project also was discussed later in one-on-one, group and public meetings on the broader Globeville Landing redesign.

"All required community relations activities have been conducted and additional extensive community outreach has been and will be conducted," the EPA stated in response to public comments.

"We probably were at 18 to 20 community meetings in 2015 and 2016," Vanderloop said. Those meetings weren't entirely about the Superfund site, but it was discussed, she said. Some of the materials presented at those meetings are available at this city website.

O'Connor argues that some of the outreach was in response to community pressure, and she points out that it came after the EPA approved the thrust of the plan.

"The Sept. 7 notice that was in The Denver Post ... gave people time to make comments, but the decision had been executed," she said. "It’s not the same process that you would have in a clean-up where you bring people together to discuss possible remedies."

Later, she wrote in an email that "the decision making that led to that agreement between EPA and Denver was deeply flawed. It was successful in keeping this discussion completely out of the public eye."

Vanderloop said that the city was following a standard course of action for this type of project. A full record-of-decision process would have involved more public engagement prior to EPA approval but would not have met the timeline required for this project, she said.

She added that the idea of conveying storm water through the Superfund site had been included both in the state's early environmental assessment for Interstate 70 and in city plans for the National Western Center issued prior to 2015.

"It’s been shown there for three, four or five years," she said. The EPA's July 2015 approval was the "first step to implementing, not the first step to planning." She said that the city has since submitted modifications and addendums for the project, which potentially could have been shaped by public concern.

What happens to the Superfund site long-term?

The city completed an investigation and study for broader work on Operable Unit 2 in 2009 and 2010. The EPA has since asked the city to do further work on the plan.

The city will hold a meeting March 13 at 6 p.m. at the Saint Charles Recreation Center to gather input from numerous groups on the larger site. The contaminated area "had been in essence capped with the parking lot," she said.

Now, with plans for National Western Center redevelopment underway, the parking area could be replaced with commercial buildings and other construction, which could require new action for the contaminated soil beneath the pavement.

Correction: This story previously stated that early CDOT plans showed an open channel through the Superfund site. In fact, the conceptual design showed closed pipes. Also, certain quotes were misattributed to parks spokeswoman Cyndi Karvaski instead of environmental project manager Celia Vanderloop.