Steve Metros spent much of his final years parked in a wheelchair at his desk in Littleton. He was in his 80s, a retiree since 1996 and a widower since 1981. For hours and days, he wrote letters in his careful hand to some of the most influential people in Denver.

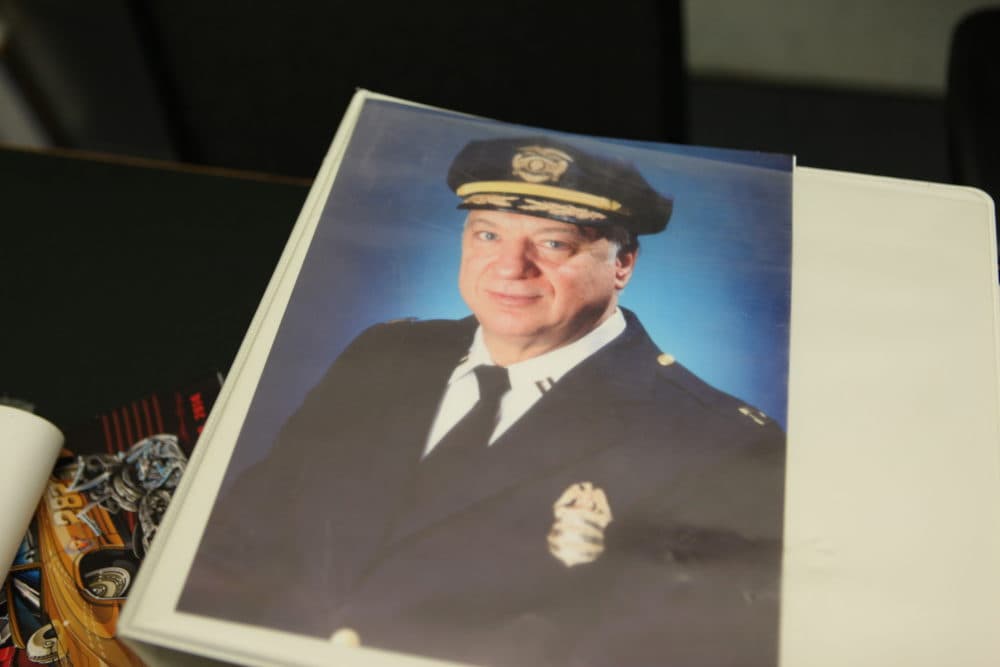

He knew that he didn't have much time left. He'd had a storied career at the Denver Police Department, having led the city's SWAT team, headed up Internal Affairs, commanded District 3 and overhauled the city's crime lab.

Now the captain had one last case to close.

"I think it was the thing that kept him going," said Michael Metros, the late captain's son. "This was his one mission, and he was relentless."

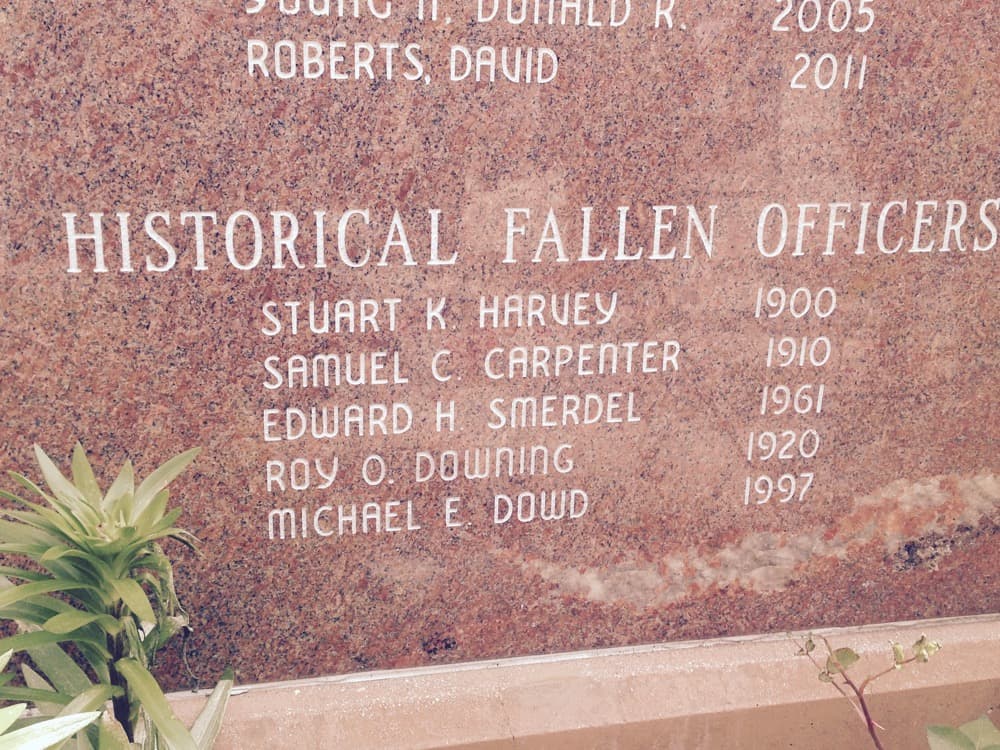

Metros' mission: Convince the department to acknowledge that Michael Dowd, his long-time friend, had been killed in the line of duty. He had for years campaigned to have Dowd's name inscribed on the memorial in front of police headquarters. And he wasn't getting anywhere.

The trouble was that so much time had passed. Dowd had died in 1997, "diabetes" listed as the cause, but Metros was convinced that his partner's death truly began decades earlier.

This story really starts in 1969.

It was November 28, to be exact –– a date that would redefine both detectives' lives.

Dowd and Metros were partners back then. They were off duty and had left Denver's City Hall just before noon. Driving West Colfax Avenue in their unmarked cruiser, they spotted a familiar face: a recently released felon in a tan Thunderbird coupe. They went to call in the license plate, but the car suddenly took off.

The ensuing chase took the detectives into an alley near The Denver Post's building in downtown Denver. The cars stopped and Metros was approaching the Thunderbird, gun drawn, when a middle-aged man leaped from the car and fled.

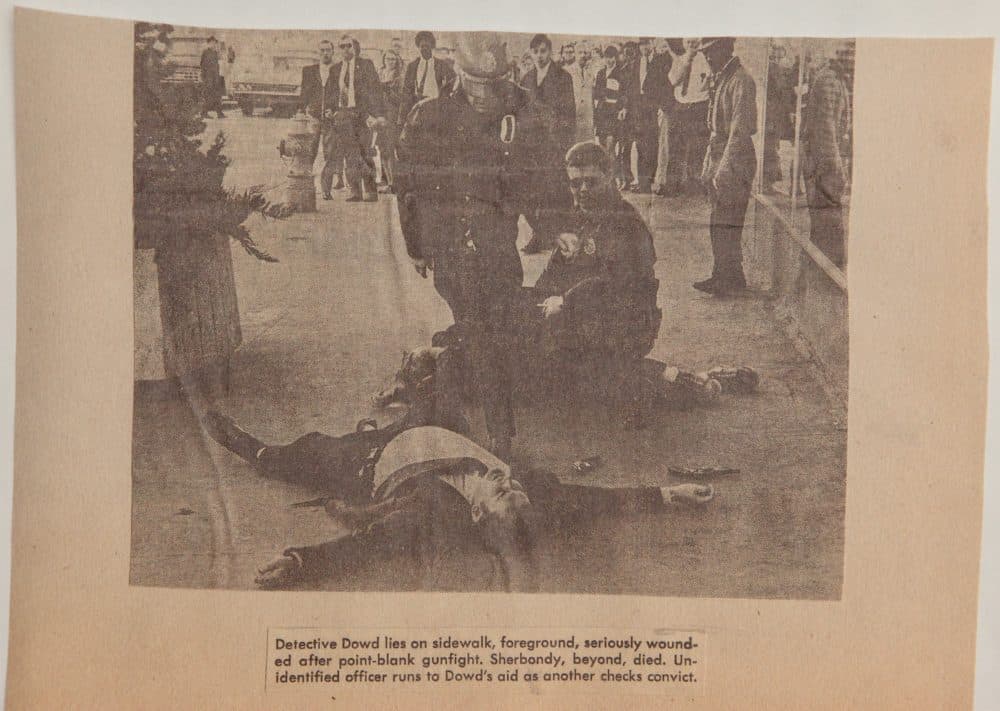

Dowd, still wearing a suit and tie from a court appearance, chased the man toward California Street, shouting, "Halt! Stay right where you're at!"

Catching up, Dowd "jumped him from behind," he later told a newspaper reporter. "He threw me off and went for his gun, and I drew mine."

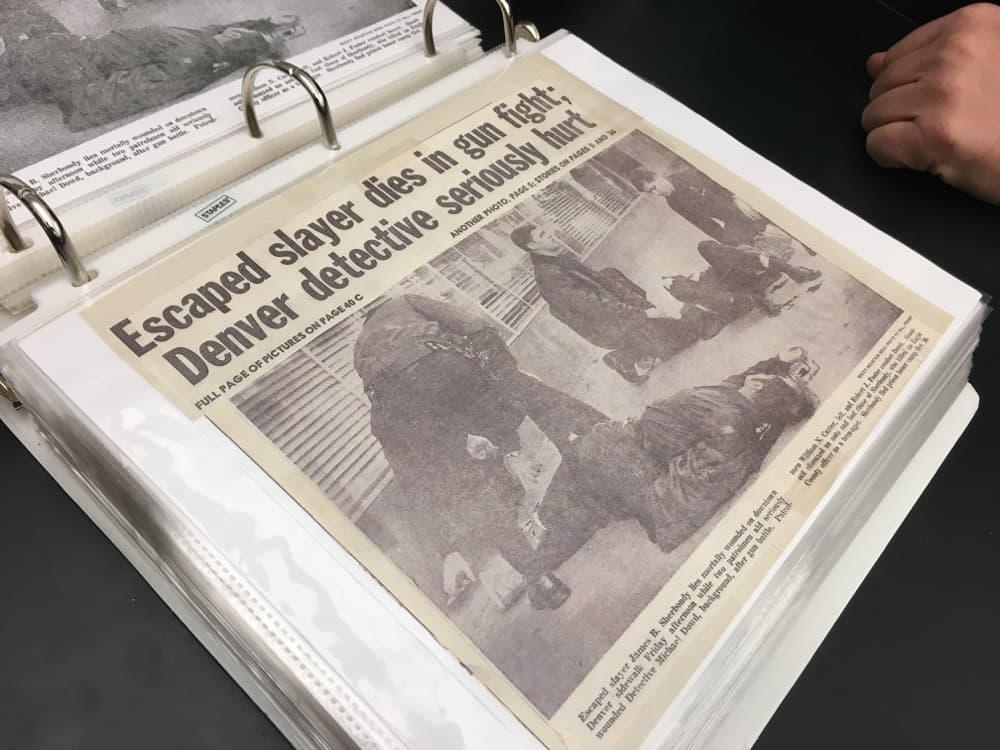

Then, according to press accounts, the fleeing man grabbed Dowd, drew a .38 caliber pistol and fired four to six rounds into the police officer's abdomen, legs, arm and shoulder. As he was struck, Dowd drew his own service revolver and shot his assailant, both men slumping to the sidewalk.

The suspect died almost immediately. Later, police would identify him as James "Mad Dog" Sherbondy, a killer who had escaped a prison camp nearly two months earlier. In his bag, investigators found pipe bombs filled with dynamite and black powder. A map plotted an escape route from the Meadowlark Hills Shopping Center in Lakewood.

Dowd later would receive the police versions of the Purple Heart and Medal of Honor for his actions.

The detective barely survived.

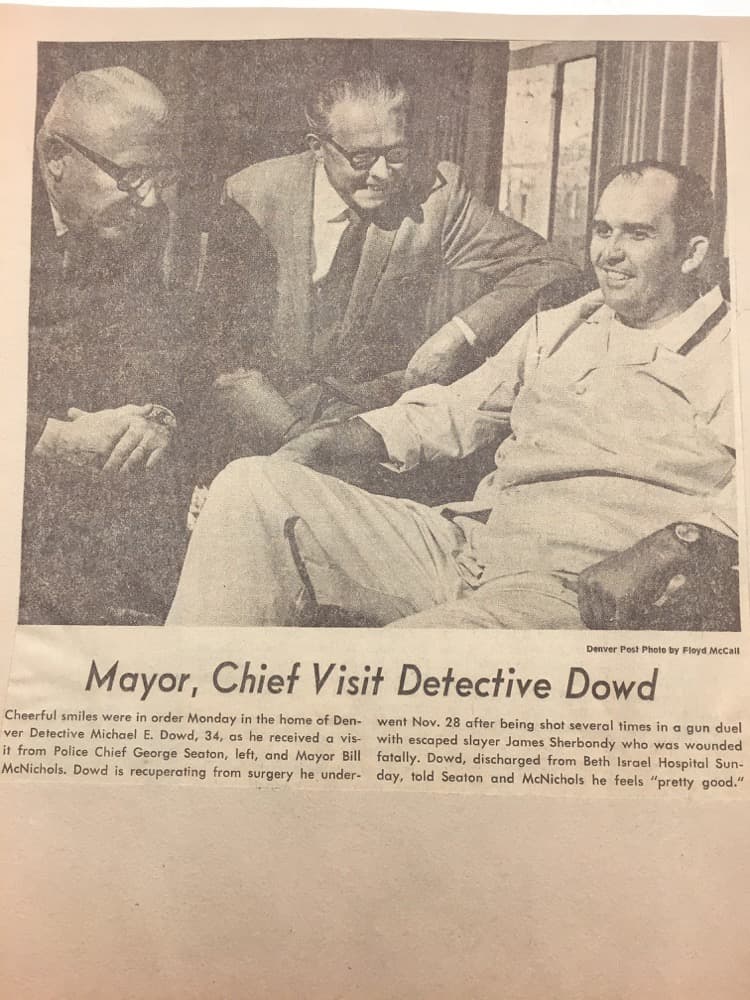

He was held up as a hero in the newspapers, which ran photos of his visit with the mayor and the chief and even chronicled his return to the hospital as his injuries persisted.

Dowd would suffer for years to come. The initial surgeries to stop his hemorrhaging forced the removal of part of his pancreas and liver. A bullet was removed in surgery nearly three years later. His pancreas was fully removed in 1974; he developed diabetes and subsequently had both legs amputated.

"His life changed," said his son, Tom Dowd. "He had five sons, and that kind of put him on the shelf from being able to do a lot of things."

He stayed with the police department, but he was unable to stay on active patrol. Instead, he became the director of the Police Activities League, where he worked with hundreds of poor kids in sports leagues.

"This was his love. Since he couldn't work the streets the way he did, he knew he could deliver with this," Metros said of his partner.

"He was, in his prior life, very athletic himself," said Christy Metros Bougie, daughter of Steve Metros. "And I think he took a lot of ownership of mentoring a lot of people through that program."

Dowd died in 1997, a stroke having left him half-paralyzed and mute at age 62. His obituary ran with his photos in the newspapers, recalling his role in stopping a violent man on Denver's streets. Even then, his family connected his decades of suffering to his sacrifice that day in 1969 -- but that's where his story seemed to end.

Years later, Metros faced his own illness.

Late in his life, the retired captain had developed spinal stenosis.

"As his own body started to fail him, he became wheelchair bound, probably for the last five years of his life," Michael Metros said. "It was during that time, he really had time to think about the past."

The Metros and Dowd families had stayed close. "My father watched him suffer, and they had kept in touch for years," Metros said.

An idea began to ferment. "In talking with me, we decided that this was actually an honest and true event -- that Mike Dowd really did die that day," he continued.

The younger Metros, a physician specializing in palliative care, developed his own theory of the case. He believed that the bullet that shredded Dowd's pancreas had resulted in severe Type I diabetes, which is extremely unusual in adults.

Over the decades, he theorized, this led to vascular disease that limited his circulation, ultimately leading to the stroke that preceded Dowd's death.

What Metros wanted was simple, but it wasn't easy.

Metros wanted to see Dowd's name on the memorial to fallen officers. He saw a direct line between the 1969 shootout and his friend's untimely death. Yet his son recalls that they encountered obstacle after obstacle.

"You wouldn’t believe it," Michael Metros said.

First, they found that the doctors who treated Dowd had died, and that his medical records at the hospital had long since been destroyed. (Ironically, a far more complete case exists for Sherbondy, the escaped convict.) So Metros conscripted Dowd's son and his own to start building the case.

"He’d always get on me: You’ve got to get your ass in gear. You’re dropping the ball on this. He just kept pushing and pushing to do this," said Tom Dowd, a high-school teacher and basketball coach.

There was also the bureaucracy, Michael Metros said. His father, despite his stature, was rebuffed twice by the department. They said that they just didn't have the evidence to put Dowd on the wall, though they'd recently added officers who had died years after injuries sustained in, respectively, the early 1900s and in 1980.

Metros figures that the new police administration simply didn't understand what Dowd's actions meant or how many lives he might have saved that day. "I think for the prior police chiefs, et cetera, this has been a legendary story for a long time," he said. But the initial response from the department was "out of hand rejection."

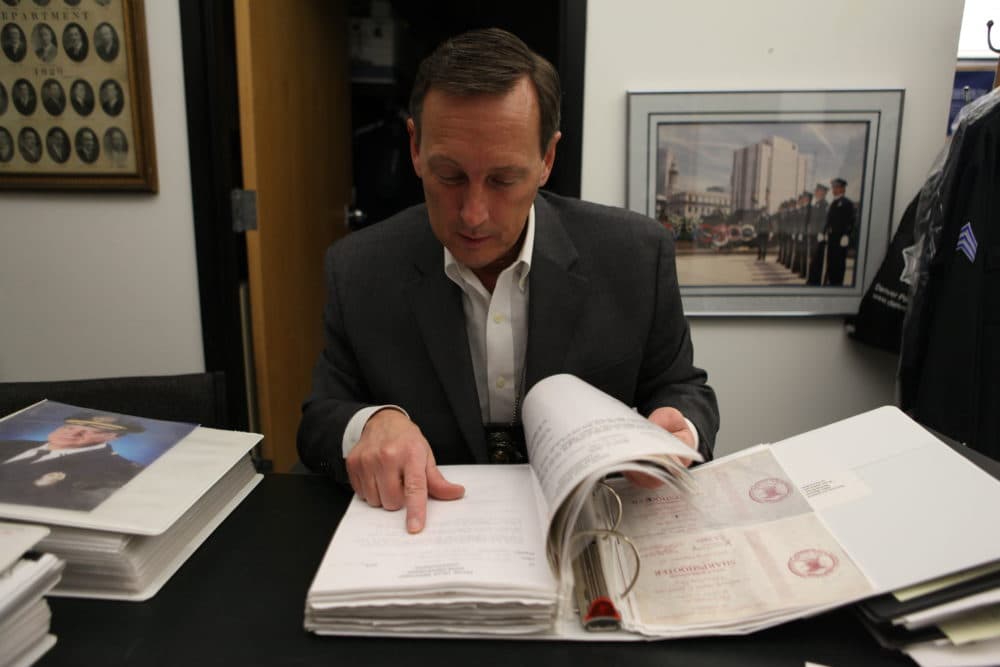

But the department had a reason to be skeptical, according to Sgt. Dean Christopherson. When he's not on graveyard patrols, Christopherson is one of the department's historians and a founder of the Denver Police Museum project. He had researched nine historical deaths of officers and knew the wall of valor perhaps more intimately than anyone.

He also knew that one of the officers on that wall later turned out to have been murdered by a romantic partner following accusations of infidelity -- not exactly a death in the line of duty, he said. Not to say that he thought Dowd and Metros' families were lying, but there's a certain significance to the wall and the lives it commemorates.

"No one should die and be forgotten by their community for enforcing the law and protecting his community," Christopherson said. But to maintain the integrity of that honor, he said, "we have to have the corroboration."

In Dowd's case, Christopherson simply couldn't find a conclusive link between the gunshot and the death, and he advised rejection of the application. When Metros asked again -- and when Chief Robert White started getting letters too -- Christopherson made his own search for records and documents, he said.

Still, no progress.

"I reviewed it three times at the request of the police department," he said. "We didn't have anything to show the medical, causal link."

An answer arrived just in time.

Dr. James Caruso had seen plenty of unusual cases before he became Denver's chief medical examiner in 2014, including countless autopsies of American soldiers and examinations of the astronauts who died in the Space Shuttle Columbia crash of 2003.

Still, the handwritten letter from Steve Metros caught his attention -- as did the follow-up phone call and the in-person visit. (Metros really was persistent.)

Caruso started following the same leads, and he sensed the same pattern of facts that the Metros and Dowd families had been arguing now for years. He also encountered the same gaps in the record.

"Any of the physicians who took care of Officer Dowd had long since died. I had no personal accounts from the medical practitioners. I had no medical records," he said.

And when he got Dowd's death certificate from Jefferson County, it listed the cause of death as "diabetes."

The medical examiner, however, had a power that no one else did: Caruso is a trained pathologist with the power to reassess the original coroner's finding.

"In my mind, if I could make a link between the injuries he sustained … and his death, and could conclude that it was a homicide, I think that would provide Capt. Metros with the kind of motivation and assistance that he needed to move the case forward," he said.

So Caruso pulled in the scraps of information from Dowd's police file, along with testimony from his family and newspaper clippings. Metros, meanwhile, had secured a letter from two former police chiefs urging that Dowd's name be inscribed on the memorial, and he was in touch with former mayors of Denver too.

This is what the medical examiner found:

"When he died, he had all the complications that come along with having diabetes for years and years. The question is, how does that diabetes originate?" Caruso said.

"In reviewing everything that was provided to me, I felt fairly confident that if it weren’t for the injuries to his abdomen from the gunshot wounds, it would be more reasonable than not to conclude that Officer Dowd may have never developed diabetes."

Specifically, one of the bullets had shredded Dowd's pancreas, impairing his ability to produce insulin and likely causing his Type 1 diabetes, which is rare in adults and for which Dowd's family had no history, Caruso said.

Diabetes, in turn, is a significant contributing factor for the vascular problems that led to Dowd's amputations and likely contributed to the stroke just before the end of his life, Caruso said.

To double-check his work, Caruso asked medical examiners in Chicago, Milwaukee and Arapahoe County. All agreed with his same conclusions, he said.

"With the information available to me at this time, the manner of death, in my opinion, is homicide," Caruso wrote in his report. And with that, he was able to issue Dowd a new death certificate, this one from Denver County, where he'd been shot so many years earlier.

"He’s the person who, for my dad, was the real hero in all of this," Michael Metros said of Caruso. "... It was finally having somebody in a position of authority who could come to the same medical conclusions that I did. That was the breakthrough that made this happen."

Everything changed from there.

With the new death certificate in hand, Christopherson could justify Dowd's inclusion on the department's wall.

Time was running short. Three years had passed, and Steve Metros' health was worsening. In fact, he had double pneumonia when the date of a new ceremony for Dowd arrived. But he was able to attend the unveiling of Dowd's name on the memorial on May 14 of that year, an event complete with 21-gun salute, honor guard and wreaths.

"Captain Metros always said, before he dies, he's going to see his partner and friend on our memorial," Christopherson said.

As Steve Metros gave television interviews, he seemed to open up about the day of the shooting and the sight of his partner in a pool of blood.

"That was the first time I’d ever really seen my dad talk in detail about it," said Christy Metros Bougie. "And the emotion, and he was tearing up about it -- it really stuck with me."

Their careers had diverged on the day Dowd was so awfully injured, but Metros had ensured that his friend would be remembered not just as someone who survived but as someone who had given his life for Denver.

"That day, that scarred him, and he always felt committed to our dad and our family, to make sure that things went right," Tom Dowd said.

And things were put right indeed, Michael Metros said. "The day of the ceremony, the police chief (Robert White) did apologize to the Dowd family, that the Denver Police Department hadn’t recognized the sacrifice that he had made that day," he recalled.

That day, Metros was able to thank all the people he'd cajoled and convinced over the years, including Tommy Dowd, whom the Metros family credits as instrumental in the process.

Metros even set a lunch date with Caruso, the medical examiner. It would never happen.

The captain's illness grew worse in the next 36 hours, and his family took him to Porter Adventist Hospital. Seeing his father near death, Michael Metros said, "Dad, you don’t have to do this anymore."

The elder Metros had finished his last duty -- and he seemed relieved. He ended his medications, spending his last days reminiscing happily with his family. He died on June 2, less than three weeks after the ceremony for Mike Dowd -- and now they both have their place in the city's history.

"You put your life on the line to do a job. Every day you go, you can not come back," Tom Dowd said. "That bond that you build ... that just kind of galvanizes them for life."

Now, he said, his own kids can see their grandfather's legacy in stone – not just in downtown Denver, but also at state and national memorials to fallen officers.

"They can go down there," he said, "and his name’s on that wall forever."