Did you know Colorado is swarming with interstellar activity?

Not only are there more than 400 aerospace companies in operation here, we're also the home of the Space Symposium. This week the 33rd annual event has pulled science buffs from all over the country into Colorado Springs' orbit. Some of those smart folks made it out on a field trip to Lockheed Martin's Space Systems facility in Littleton, and Denverite got to go along for the ride.

Along the way we got to gawk at four areas of work that might help lead mankind into a Jetsons-like future. Here's what we saw:

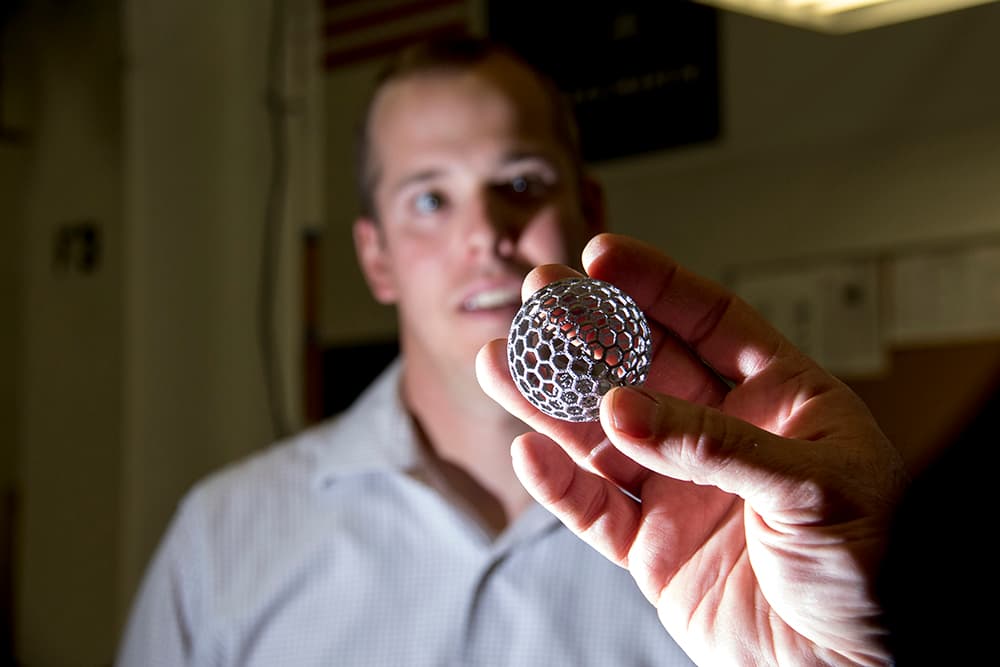

Satellites you can print

3D printers have been the talk of DIY hardware hackers for a few years now, but the technology's more recent advancement into stronger materials has made it incredibly useful for industry. Lockheed has a whole lab dedicated to 3D printing with titanium and hearty polymers.

Though they've started small (there's currently a 3D-printed bracket orbiting Jupiter), engineers here hope future satellites will be constructed with a significant percentage of printed components. Printed parts are generally lighter and quicker to make, and the technology could reduce satellite production times from as much as 40 months to as little as 18 months.

On a smaller scale, interplanetary planners see a use for 3D printing as a way of reducing the amount of gear astronauts would need to bring on board a spacecraft bound for, say Mars. Why bring a wrench when you can print one -- IN SPACE!

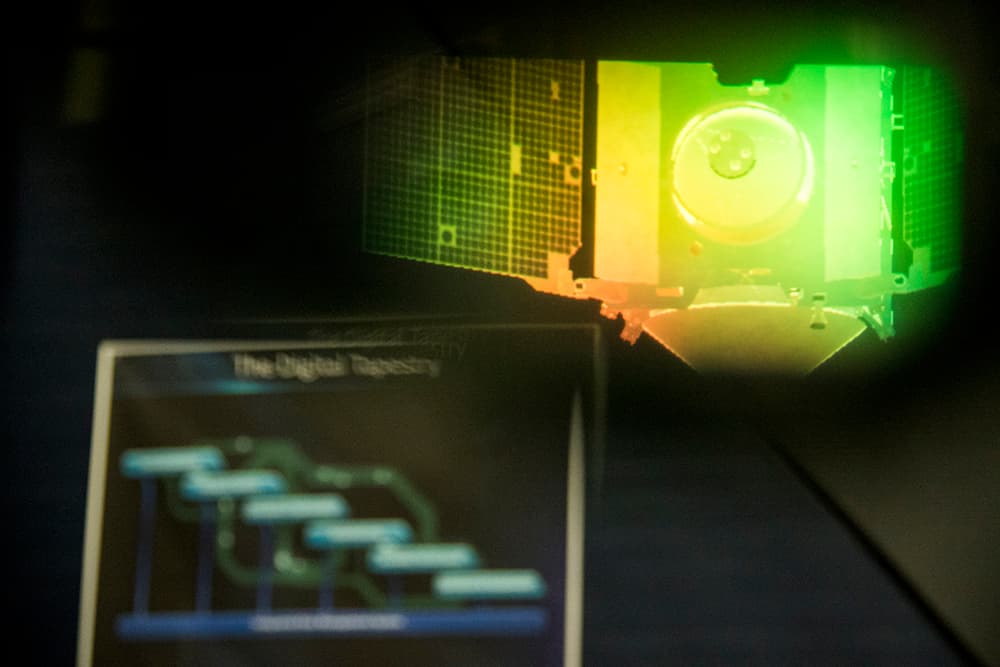

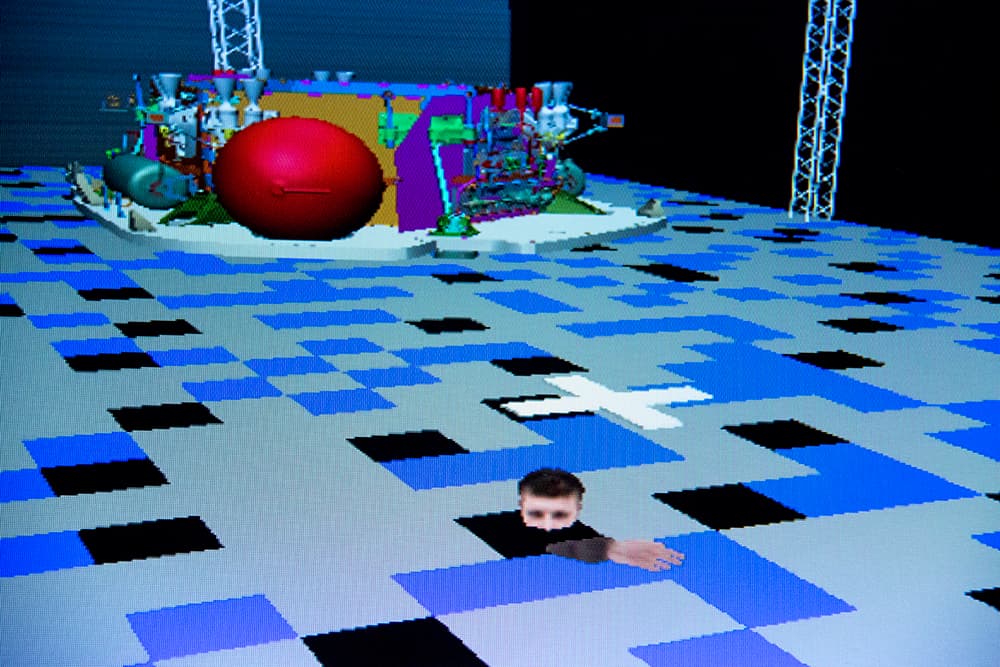

Virtual reality engineering

Another major effort at the Littleton facility is the development of immersive virtual reality platforms. Like the 3D printers, this is aimed at speeding up development time. Instead of building costly prototypes, engineers can see how pieces come together in a virtual environment.

Furthermore, workers across the globe can meet up online in a Matrix-like platform to collaborate without having to buy plane tickets. So far, engineers have not donned blacked out shades and trenchcoats.

The CHIL, or Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory, puts a range of technology to work, and some of it is not all that out-of-reach. Ten years ago they built a motion capture studio (think, Gollum), one of the only ways to beam a person into cyberspace. Today though consumer tech in this field has exploded, and Lockheed has put much of that to work here as well. The HTC Vive and Oculus Rift headsets are now staples of the lab's work, as is the Microsoft Hololens.

These new systems are much smaller than Hollywood-grade motion capture stages and offer a lot of new possibilities for collaborating engineers. I put on the Hololens and was delighted to walk around floating 3D models of satellites floating before me.

Lockheed's VR tech also has space travel applications. It'll take about a year for astronauts to reach Mars, and virtual reality will help NASA's finest from going nuts in transit.

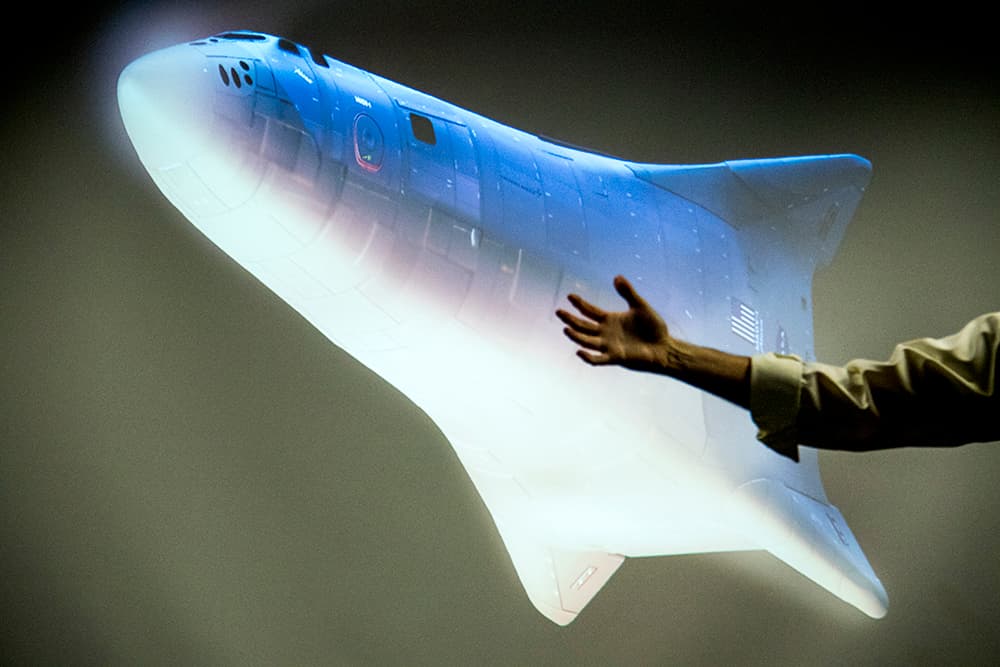

The vessel that will bring us to Mars and the port that will keep us there

In 2006 NASA granted Lockheed Martin the contract to design and build the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, meant to bring man to Mars by mid 2030. Since then they've managed to build and launch an unmanned test of the vessel. Today the craft's second iteration is in development in Littleton.

NASA still has a lot of planning to figure out how to get humans to the red planet. Since they're already making the spacecraft, Lockheed is trying to pitch an add-on space station that would orbit Mars and serve as a base for interstellar scientists.

The "Mars Basecamp" concept envisions a structure that could accommodate two Orion spacecrafts. At 80 percent the size of the International Space Station, six scientists could live relatively comfortably while exploring Mars from a distance. Rovers on the surface today can be controlled from Earth, but there's a 20-minute communication delay, which means those robots can't really be piloted by hand.

Scientists orbiting the planet would be close enough to explore the red landscape with a joystick in realtime. The base would also allow manned crafts to land on the surface, making mankind Earth's first inter-planetary species.

A finer-tuned GPS

This is probably the least-exciting-sounding innovation and the one that has the most impact on you. Lockheed holds the contract to produce satellites equipped for GPS III, a new standard that is yet to be deployed.

Lockheed does this in an enormous top-secret clean room where the devices are currently in various phases of development. Part of this facility is a chamber bigger than my apartment that nearly mimics the vacuum of space.

The last time we achieved GPS standard goals was in 1995, so there's definitely room for improvement 20 years later. The new standard will triple our systems' accuracy and also make it more secure.

But this isn't all about finding your way to the mall. GPS is used for synchronizing timing in a number of industries. Financial transactions, energy production, wireless communication and transportation safety mechanisms all rely on this satellite technology. The new standard helps keep our totally tech-entwined lives from falling suddenly into chaos.