Denver Public Schools is seen nationally as an urban success story, racking up kudos for its academic growth, robust school choice process and teacher leadership programs.

But a new report finds that while the 92,000-student district is indeed improving, opportunity is “unevenly distributed.” White students and those who are more affluent, it notes, are making more progress than low-income students and students of color.

“It is true that Denver is one of the most-improved large school districts in the state,” said Van Schoales, CEO of A Plus Colorado, the advocacy group behind the report, which is called “Start with the Facts: Denver Public Schools.”

“And it is also true that not everybody in the school district has benefitted equally from those improvements.”

Here are some of the report’s key findings:

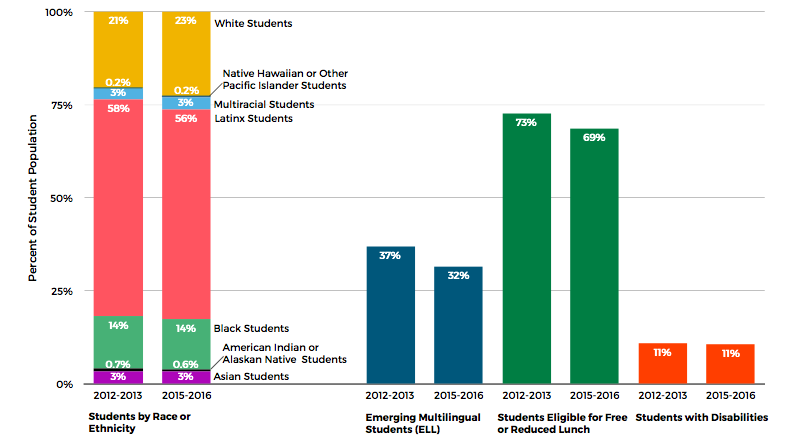

DPS is getting more affluent and the number of white students is on the rise.

In the 2012-13 school year, 21 percent of students were white, 58 percent were Latino and 14 percent were black.

In 2015-16, the percentage of black students held steady, but the percentage of Latino students dropped to 56 while the percentage of white students rose to 23.

Meanwhile, the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, a proxy for poverty, decreased in that same time period from 73 percent to 69 percent.

The likely cause, the report says, is gentrification.

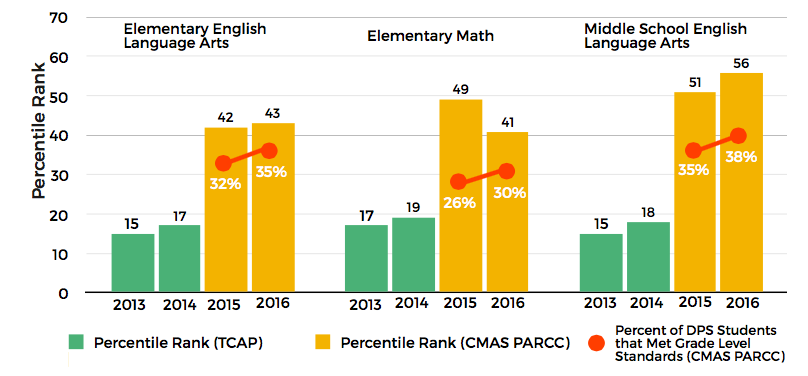

DPS is doing better on state tests than it used to when compared to other districts in the state.

The improvement is drastic: For example, the report says DPS elementary students ranked in the 15th percentile on state English tests in 2013. By 2016, elementary students ranked in the 43rd percentile — and that was after Colorado switched to new more rigorous tests.

However, the percentage of DPS students scoring at grade-level on those tests “is still far below what we should expect,” the report’s authors noted.

In 2016, only 35 percent of elementary students scored at grade-level in English. That’s far short of the district’s own goal that 80 percent of third graders be reading on grade-level by 2020.

And some groups of DPS students are making academic progress faster than others.

The report finds that white DPS students, for example, are making more gains in math year to year than their academic peers (students across the state who had the same test score the previous year). Meanwhile, black DPS students are making less progress than their peers.

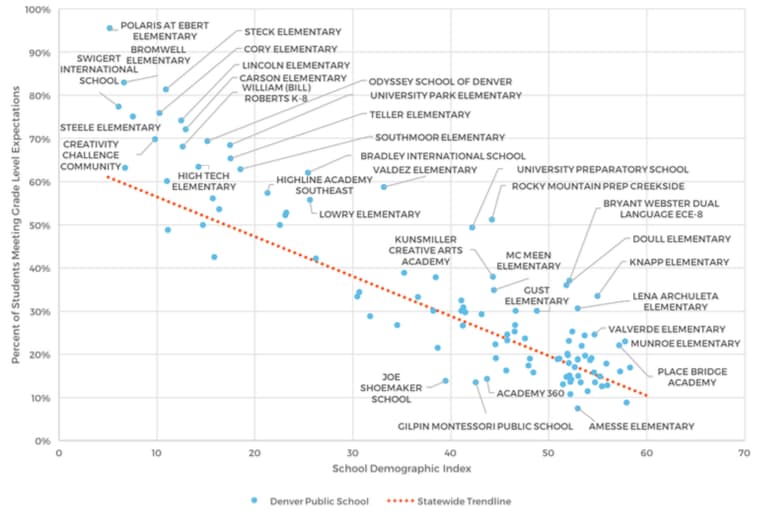

But a sizable percentage of DPS schools — more than one in four elementary schools — are bucking the trend.

At those schools, which the report calls “positive outliers,” students are reaching grade level at higher rates than students at other Colorado schools with similar populations of low-income students, English language learners and special education students.

Notably, the outliers include all types of schools, from charters such as Rocky Mountain Prep to innovation schools such as Valdez Elementary to traditional district-run schools such as Doull Elementary.

The models are also diverse; they include dual-language schools, experiential learning programs and more structured no-excuses schools.

“One of the takeaways from that analysis is that it shouldn’t be just one kind of school the district focuses on replicating or reproducing,” Schoales said.

While DPS graduation rates are increasing, the percentage of students who attend college is stagnant. And only half of those who do are college-ready.

In 2015, 48 percent of DPS graduates went on to attend college. That’s essentially the same percentage as in 2009, when 47 percent of graduates did.

The percentage of them who needed to take remedial courses, for which they don’t earn college credit, decreased from 63 percent in 2009 to 53 percent in 2014. But the report concludes it’s still too high.

The report offers several recommendations to fix the issues facing DPS. They include:

Address the segregation that can be caused by gentrification by reserving seats for low-income kids at schools with more affluent attendance boundaries or improving transportation options for low-income kids living in neighborhoods without quality schools.

The effects “could be incredibly powerful,” the report notes, “as in many cases it is integrated schools that are showing the best results for low-income students or students of color.”

More closely evaluate which of the district’s many improvement strategies are working.

“The district has engaged in a million different projects and efforts,” said Schoales, including new literacy programs, teacher development initiatives and flexibilities around curriculum. “We don’t know which of those is really working and which of them really isn’t.”

Refine DPS’s color-coded school rating system so that it’s two purposes — helping parents understand how a school is doing and helping the school understand whether its efforts are working — aren’t at odds. Right now, students at some schools rated “green” — which parents read as “good” — have only a “small likelihood” of being on grade-level, the report says.

On the whole, Schoales said the report’s message is a complicated one. While the district has made progress, he said, that progress hasn’t come fast enough — though the positive outlier schools show that it’s possible for DPS schools to achieve extraordinary results.

Read the entire report below.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.