Even if you're not religious, nothing feels more immutable than a church. Every once and while, I wonder what it would be like to greet the morning in the quiet of the cavernous hall of St. John's Cathedral. I never do though, maybe because I've always assumed it would be an option.

But actually, one out of every five churches in Denver was part of a sale within the last eight years. And some don't stay churches.

In Denver, we have churches that have become clubs, churches that have become art galleries, even churches that have become homes. And the number of churches that have been repurposed is only poised to rise.

At one point, churches were the bedrock of American social life, and skylines reflected that with dramatic architecture that punctuated every city landscape. Now, many of those original tenants face mounting operational costs and dwindling congregations.

Right next to the big spiritual question of faith in American life, there's the more pragmatic question: How do we use these big, grandiose buildings?

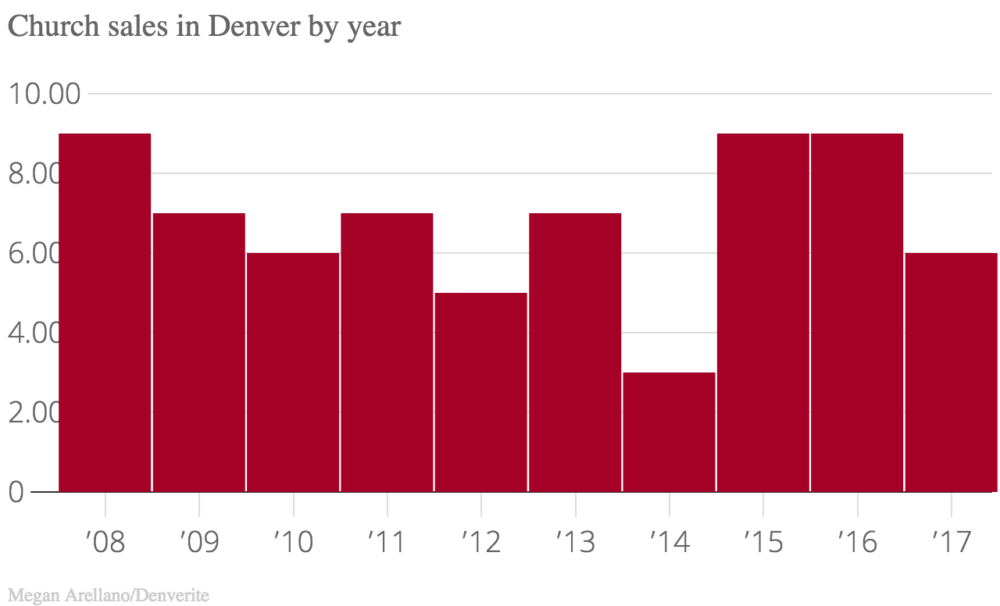

In the past few years, there's been an increase in the number of churches sold, according to a Denverite analysis of the city's real estate sale data.

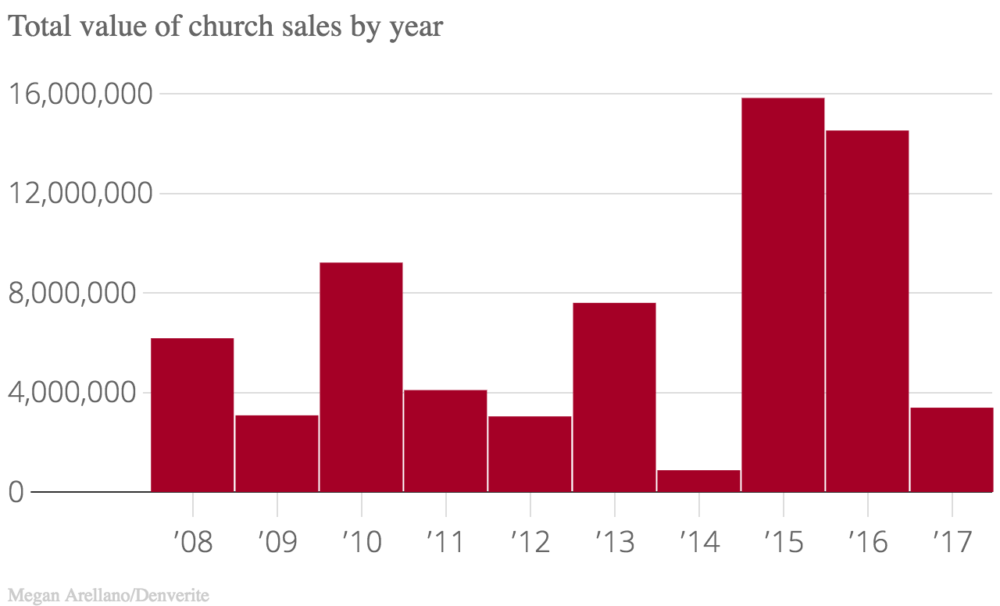

There's also been an increase in the church sale prices, perhaps indicating increasing interest in these properties.

For a developer like Fred Glick, whose firm bought a church of their own at 49th and Zuni in January, these buildings represent an intriguing challenge. They're big, open spaces, designed for a single purpose and they don't always lend themselves well to conversion to another use. Then there are the maintenance costs:

"I looked at a historic church in Cap Hill that needs $150,000 worth of base rework pretty urgently. That same church has a furnace that's not in good shape," he said. "Some of those kinds of churches that are independent, that's a lot of money to come up with to maintain a building."

Glick and his partners plan to turn the new acquisition into neighborhood retail space. Done well, Glick says churches boast beautiful volume and irreplaceable historic features.

But because many churches were zoned for residential use in Denver's big 2010 rezoning, housing can be the most natural fit for these rebuilds. The modified buildings can command as much as $1.85 million for one tenant or as much as $770,000 for 12 tenants, in the case of the Sanctuary Lofts.

A view inside 2283 Ogden Street from 1955 on the left, and a view from 2016 on the right.

A slim majority of Denver churches are still being bought by faith communities.

Overall, only 40 percent of churches were sold to developers over the past eight years -- with others being bought by people who intend to continue using the buildings as houses of faith and spiritual community centers.

But what kind of church can afford to buy a million-dollar building in an era when Denver real estate only seems to be getting more expensive?

"We're lucky that we have a couple other churches supporting us," said, Zack Weingartner, Denver campus pastor for Flatirons Community Church.

Flatirons is the Colorado "megachurch" that commands as many as 17,000 people per service and has a 162,000-square-foot campus in Lafayette -- and has a habit of making real estate news.

Weingartner says they decided to expand into Denver roughly two and a half years ago when they noticed that they had a number of people coming to services from the city. Those worshipers guided Flatirons to its new location around the University of Denver, where they purchased 2700 S. Downing St. for $1,249,000.

The building that had fallen into neglect, according to Weingartner.

"The church that we purchased was built by Swedish immigrant families in the 1940s and it's a beautiful old building, but it was done," Weingartner said. "The ability to breathe life into something that's been there for almost 100 years in a beautiful neighborhood is really exciting to us, we really love that aspect of it."

And no one likes to see a building go unused. Even Denver's pot church -- and at least one neighbor -- pointed out the same thing.

The Zen Center of Denver has a different approach for their new home in the DU area. They're going to build it.

"By nature, if you're looking to get a historic building and you're looking to get a reasonable price on a historic building, it's probably not in very good shape," said Joel Tagert, office manager for the Zen Center of Denver.

They would know. The Zen Center of Denver sold the church that they had been using for $1.8 million in 2015.

"We got a very good deal in 1998 but knew that substantial renovation and repairs would be required," Tagert said. "Over the course we were there, we spent hundreds of thousands of dollars renovating and repairing."

With their relatively smaller congregation of about 70, the Zen Center decided that they had more space than they needed at costs that didn't make sense for them. After they sold, they found that the spaces they could have purchased all needed significant repairs. So eventually they decided to buy a plot and build their own space.

"When you build from scratch, you end up with a space that's perfectly suited to your use and aesthetics," Tagert said. "It can have the indoor and outdoor space. When it came down to it, we were looking at spending just as much on renovating as just purchasing a plot."

By now, you get it -- paying for church upkeep is expensive. But churches also face a challenge in the way Denver is changing around them.

On paper, the Church of the Advent looks like another face of the new faith community that has a young enough and strong enough congregation to buy a church.

Pastor Rob Paris started the church in Baker in 2011, renting space from the Mi Casa Resource Center. Last year, they bought a building for $865,000. And like Flatirons, they're also part of a bigger faith community -- Wellspring Church in Englewood.

"A lot of our church was coming from south, plus we were interested in being off I-25 and being in a good location to start other churches," he said.

But the Baker neighborhood changed quickly in that timeframe, and Mi Casa Resource Center sold the building that they were renting. Paris said they would have liked to stay in Baker, but prices were challenging in a variety of ways.

"The desire to reach poor and rich was a lot harder when there wasn't as many poor people there. But that wasn't the driving factor, a lot of it was that our church could not afford to buy anything in that neighborhood," he said.

Now even their new location in Villa Park is starting to gentrify, Paris says. Though he says the church isn't equipped to resist gentrification, he's not too worried about it for the moment. It helps that his congregation is made up of younger people.

"We bought our building from a church that had been here for 100 years that had just slowly lost its membership to mostly people dying," Paris said. "So they just realized that they needed to do something before it was too late and be able to sell their property before they didn't really have the ability to control that at all."

In some neighborhoods, churches aren't changing hands at all.

There are pockets of the city where the disruptive forces of aging buildings, aging congregations and gentrification haven't dislodged these institutions. At least in terms of the city sale data.

Five Points stands out in this regard. Despite immense change, there have been relatively few church sales in the area. Only 3 of its 19 churches have sold in the past eight years. Likewise, nearby Skyline and Clayton have seen only one church sale among their 23 collective churches.

Zion Baptist Church Historian Clementine Pigford says that at least for her church at the corner of 24th and Ogden, early and continued changes may have insulated the congregation.

First, as the self-professed oldest African-American church in the Rocky Mountains, formed in 1865, Zion Baptist has already seen its congregants move. That started happening back when restrictive housing covenants in Denver were lifted, said Pigford. In turn, the church doesn't necessarily rely on drawing from a congregation that lives in walking distance.

Another thing helping to protect Zion from change is that, as a historic church, the facility has a draw that you can't get anywhere else.

"It really is the history of a people in Colorado, I'm not trying to sound dramatic or grandiose, because we've been able to track the pioneers of Denver and the Colorado territory to our members," Pigford said. "So many of our members were firsts and that's significant to me because it allows me to find intimate history about the territory."

But it's not so much about the neighborhood itself:

"At one time, it was very impactful because that's where African Americans, if they did not live there, they played there, it was a hub of activity for a while, that's where a lot of good churches were," Pigford said. "But the entire neighborhood has changed."

Fellow historian Annette Groves, who has been going to Zion for 70 years, agreed:

"The neighborhood has changed so much. I don't really have a reason to stop, I don't have friends or relatives any longer in the area anymore. And being older, I come home," she said.

Still, there is something special about having occupied the same space for so long.

"I'm very proud and my heart is touched that Zion Baptist Church is still standing there, still worshipping, still helping others, still doing what we should be doing as a church, even though the entire setting around us has changed," Groves said.

Methodology: I used Denver Real Sales and Transfer data from June 2017 to come to these figures. First, I selected all Denver class buildings that were either classified as "CHURCH BUILT AS CHURCH" or "CHURCH-CONV FRO OTH USE". Then I filtered those sales based on deed types to remove parcel combinations, parcel splits and other deed clarifications. After removing duplicate sales, that left a dataset of almost 70 church sales.

To determine what share of these churches were bought by developers, I conducted independent research based on available websites and Colorado Secretary of State filings.