Aaron Walbert's fingers curled and tapped on the bar of the metal frame that kept him upright. His attendant, Jennifer Hill, had just asked him what he likes about living in his own condo.

He was silent for a few moments more, looking as if he was in a far away place, until he found his answer.

"Freedom," he said in his slow rumble.

"Remember when I asked you, last night, how would it be?" his home aide prompted him.

"Why are you crying?" he asked her instead, seeing the tears at the corners of her eyes.

One answer was that she was exhausted. It was 8 p.m. now and she had been up before 7 a.m. to help Walbert through his morning routines, with a stop at a protest near Sen. Cory Gardner's office at mid-day.

But it also was the uncertainty -- the looming question of whether the Republican health care plan would indirectly force Walbert out of the home he owns in Capitol Hill.

In recent weeks, people with disabilities have been at the heart of Colorado's debate over Republican plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Their arguments have led Republicans to add money for community-based services to a revised version of the Senate bill, and some GOP lawmakers are seeking greater protections for traditional Medicaid populations, including people with disabilities. But advocates say it's not nearly enough.

Aaron Walbert has a lot to lose.

He is a member of a rare group: Those with significant cognitive and physical disabilities who nonetheless have been able to purchase and maintain their own homes.

Changes to Medicaid's structure could endanger his independence by indirectly cutting the funding that pays for the services he uses at home and in the community.

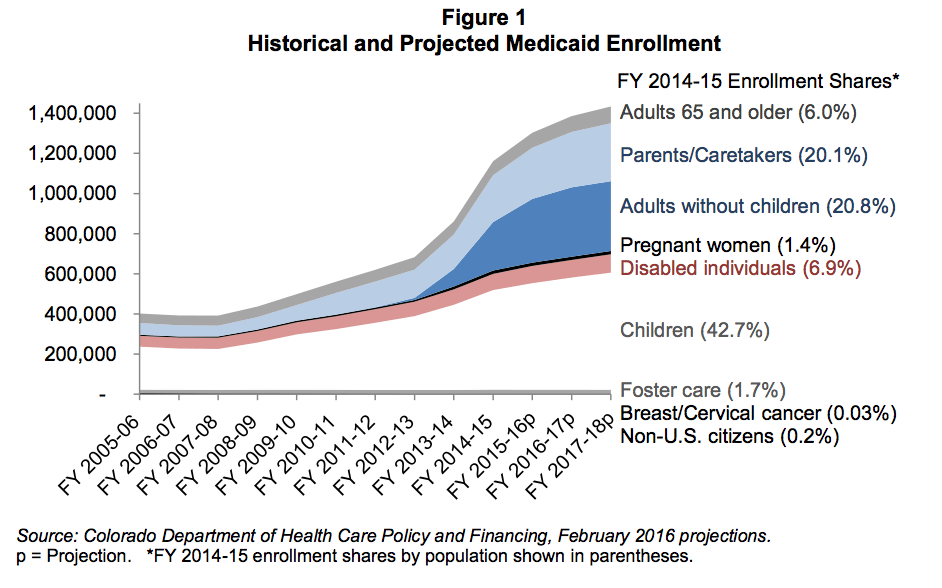

Among the most contentious items still in the bill: A reform of Medicaid funding rules that by 2025 could cut 26 percent of expected money for the national program, which provides health insurance for elderly people and those with low income or disabilities.

"They cut way deeper than what the (Affordable Care Act) added to expenses. They cut severely into traditional Medicaid," said Josh Winkler, board co-chair of the Colorado Cross Disability Coalition.

"If you cut Medicaid spending across the board by 26 percent, there’s no way that you can do that without adversely affecting seniors and people with disabilities."

The Congressional Budget Office hasn't yet scored the latest revisions, but they're expected to have similar impacts, fulfilling a longtime conservative goal of reining in a program some see as bloated and wasteful.

With Colorado's tight budget, a cut could force difficult decisions.

Would lawmakers cut off benefits for the 450,000 people who were included in the Medicaid expansion, which provides health insurance for nearly 19 percent of people in some rural counties?

Or would they roll back optional benefits, such as the money that pays for Hill to attend to Walbert for six hours each day?

"What would happen in Colorado is that they would start having to make very difficult decisions," said Walbert's mother, Renee Walbert, herself an employee of Parent to Parent, a disability services nonprofit. "If I were going to take an educated guess, they would start with across-the-board budget cuts."

What disability advocates fear is the ripple effect. With record low unemployment, even a small reduction in wages available for attendants like Hill could make it impossible to find someone who could help Walbert in and out of his clothes or into his exercise frame or help him fulfill the decisions he makes.

And with rules that prohibit certain benefit recipients from keeping more than $2,000 in cash, the effects would hit Aaron Walbert fast.

Renee Walbert's first hope was that her son would survive childhood.

He was born 10 weeks early and suffered a stroke that would fundamentally alter his physical and cognitive abilities.

"My only goal when he was little to keep him alive. That was it," his mother reflected, seated late one evening at her son's kitchen table.

Somehow, somewhere along the way, their goals for Aaron started looking a lot more typical. "I suppose we started talking about it the same age as other people do: 'What do you want to be? What do you want to do?'"

At age 19, Walbert moved out of his parents' house. Now he's 30 and a homeowner, with much of his mortgage payment covered by an affordable housing voucher.

"Aaron chose this place," his mother explained, motioning out to the black couch and the Japanese tchotchkes that Aaron Walbert has curated. "He looked and looked and looked. He wanted a first floor apartment with direct access to the outside because he didn't want to wait to be rescued."

"Haven't I told you, you’re the best boss ever?" Hill said slyly, catching Walbert's eye.

Walbert is able to directly manage the money that he gets from his Home and Community Based Services voucher. He gets to choose whom he hires as his attendant and, in fact, has fired one.

"He has everything that he needs to survive up here," Renee Walbert said, tapping her head. "And he has room for fun stuff too."

He can be shy, sometimes responding to strangers with indistinguishable croaks. Sometimes he seems to be swimming in his own mind, searching for words.

When he finds the groove of a conversation, though, he keeps pace easily, offering insights and occasionally needling his friends. He also has an excellent memory for addresses and telephone numbers, which comes in handy when he needs to call for an accessible van.

He works a few hours most days at an ARC Thrift store, where he loves to answer the phone. He very much leads his own life, often occupying himself by visiting a meticulously catalogued set of coffee shops and, occasionally, the neighborhood bar.

The benefit of all this, Renee Walbert said, is stability. The federal government is able to ensure Aaron Walbert is housed for a fixed price, which was locked in years before the housing crisis. "They never have to pay anything more," she said.

For Walbert, the condo and his services at home have helped him build routines that are crucial in navigating the world.

And it would have been impossible a few decades earlier. Prior to 1981, elderly people and those with disabilities were far more likely to end up in nursing homes funded by Medicaid.

That was because there was little funding for the kind of basic, non-medical services that would have helped them live outside of institutions.

A new law in 1981 opened up far more community care options. The Affordable Care Act also provided new and expanded options for states to fund these kind of community programs.

The disability advocates' arguments are gaining traction.

"It’s not that the Senate and the House bill are targeting home and community-based services, but they’re targeting Medicaid," Renee Walbert said. "What ends up happening is everybody thinks that somebody takes care of those people. Well the somebody is ... it’s Medicaid that pays for this."

That argument has proved potent, grabbing national attention when protesters occupied Sen. Cory Gardner's office in Denver. While the protesters didn't immediately get a response from the senator, the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition recently had a call with Gardner, according to Winkler.

"I suspect what we’re telling him and what leadership in the Senate is telling him is very different," Winkler said.

"My hope is, when he sees the truth about it, that our services will be decimated, that he could be moved to a no vote."

There's also the possibility that Republicans will further move to protect funding for people with disabilities while still eliminating money for the care of low-income people.

Linda Gorman, an analyst with the conservative Independence Institute, said in an interview that it wouldn't be bad for states to make that choice. She argued that the low-income adults Obamacare added to Medicaid are competing with people with disabilities for those federal dollars.

"If your goal is to make sure that people who need sophisticated medical care get it, then putting a bunch of healthy people into Medicaid doesn't help," she said. "The reason Medicaid was created was to take care of people who couldn’t take care of themselves."

Medicaid's first recipients in 1965 included low-income "families with dependent children" and people with disabilities. So, from some conservative perspectives, the threat to Aaron Walbert comes not from the cuts but from the expansion of Medicaid over the years.

Some Republicans are pushing for changes to the plan.

Republican Congressman Mike Coffman of Colorado has a proposal that would protect the traditional Medicaid population, including people with disabilities, while rolling back federal funding for the expansion population.

And Gorman, for her part, doesn't think the new "per capita" limits on federal funds should apply to people with disabilities.

"I think that it’s a mistake to do capitative payment for seriously ill groups, which is what this is," she said.

The newest version of the bill does try to compensate by making $8 billion over four years available for home-based and community services like Walbert uses. That money would largely be meant for 15 states with low population densities, including Colorado.

"That would be a lot for one state, but it might not be much if a lot of states get the funding," wrote Joe Hanel, an analyst with the Colorado Health Institute, in an email. (Colorado alone spent more than $800 million in the last fiscal year on long-term community care services.)

But Cross-Disability Coalition members were not impressed with the changes, and they did not mince words in a press release after the revisions to the Senate bill were announced.

"The revised version of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) confirms that some want a second eugenics movement," they wrote. "A more fitting title for the proposed legislation would be 'After 2023, Seniors and People with Disabilities will Die Act of 2017.'"

The extra money for home and community services would "do little except for delay massive cuts for a few states," they wrote.

Winkler, the CCDC co-chair, who himself has a disability, said Rep. Coffman's plan is a "step in the right direction," but he remains skeptical of the overall Republican approach.

The current plan is "going to pit the women and children against the cripples and the old people," he said.