Kendall Smith: Imagine standing on a 65-year-old’s back porch trying to explain Big Freedia’s performance the night before, while A Place to Bury Strangers launches into their set -- one of the loudest bands ever -- and he’s asking me, “Why don’t you go over and turn that down?”

John Moore: We’ve always been cognizant about those issues, but there’s only so much you can do. It is a music festival.

Kendall Smith: There are angry people all the time. You know, nothing is for everybody.

Marty Levine, president, Broadway Merchants association: I think we have some merchants that are not on the happy side.

Loretta Koehler, Baker Historic Neighborhood Association board member, 18-year resident: Initially it was small enough that it was easy to get around and it was pretty fun. And then it got so big.

Esmé Patterson, musician: My favorite metaphor for it is that it’s a real main artery of the music scene in Denver. I’ve been lucky enough to play it over the course of many years, and watching the festival develop has been like watching Denver develop. It started out very underground and now it’s more above ground, it seems, getting bigger and bigger and more exciting. It’s sort of a microcosm for Denver in general.

John Moore: As we sit here 16 years later, I sit there and go, you know, this is the perfect location to do this conversation, because my memories are coming here a couple of days before the UMS and Rick would have tarps and spray paint and we would just be spray-painting signs that say “UMS is for lovers” and we’d get paint all over ourselves making these banners.

Ricardo Baca: It’s the night before the event starts, and that’s how we started.

John Moore: It’s just a bunch of friends getting together and putting on the biggest party that you could put on. And what’s happened is the natural progression of all that love.

On a mild summer evening in Ricardo Baca’s half-wild-west Denver backyard, the two co-founders of the Underground Music Showcase, Baca and John Moore, and its current executive director, Kendall Smith, told the story of the UMS in a conversation that lasted two hours, interrupted only by the cracking of beer cans and the barking of Baca’s dogs.

(This year's UMS is happening Thursday through Sunday, July 27-30. Four-day passes are $55 in advance and $75 on site.)

The three men each had a turn at the helm of what’s now a four-day showcase featuring upwards of 300 artists in more than a dozen venues along South Broadway, and the transitions between them mark significant transitions for the festival -- the year it jumped from the Bluebird Theater to the venues of Baker and the year the Denver Post took over.

In meetings, phone calls and emails, UMS staff, local musicians, South Broadway businesses and neighborhood residents recounted their experiences, too, filling in the blanks in the story of a Denver institution 16 years in the making.

“So that first year there was no, like, greater plan of creating a festival.”

John Moore: The first conversation was between myself and Ed Smith, who was the arts and entertainment editor at the Post at the time, and I had just recently switched over from sports, where I was deputy sports editor for seven years. And I always had a great love for the local music scene.

Seven years is a long time and I didn’t know the scene anymore. I said, “I just need to completely immerse myself in the local music scene.” And coming from a sports background, where we have top 25 college polls and things like that, I’m very much about numbers. I came up with this idea for a poll, and I said, "What if I just survey a bunch of talent buyers and bookers and people who go to shows four or five times a week and do it like it’s a top 25 college poll?” I thought the poll sort of exonerated me from having to make any sort of really hurtful, sort of subjective thing.

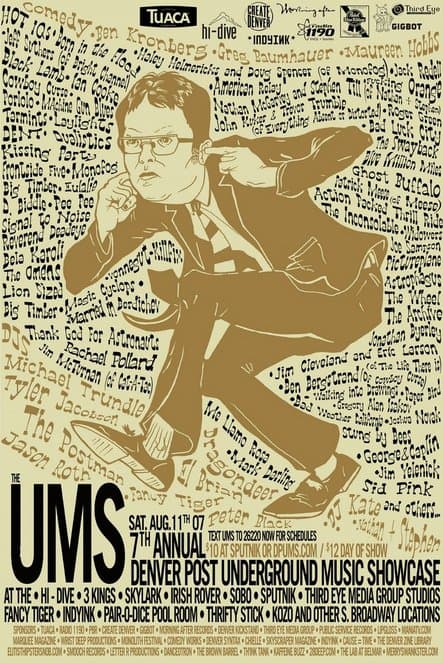

So I posed the original question: Who are the underground bands in Denver? The results came out and 16 Horsepower was way far and above at the top of the list. And so that first year there no, like, greater plan of creating a festival. And for its early years I felt like we were -- it was like we were putting up a live mirror to history.

After interviewing David Eugene Edwards of 16 Horsepower for a feature, Moore decided to run the story in conjunction with the band’s next show one month from then at the Fox Theatre in Boulder. They didn’t have openers set up, and the Fox let him add a couple of the local bands in the poll’s top 10.

This was 2001, and that was the first seed planted.

John Moore: My boss loved it and he loved the response it was getting, and he was sort of saying, "Well, we could do this every year." And so, like, six months later when we were talking about it coming up again, that’s when I was like, "Well, let’s think big. Let’s do the poll well in advance. Let’s get a top 10 together, give those top 10 names to someone like Jerri Thiel and say, "Can we have a night with local bands who finished in the top 10?"

Rick Baca came up with the UMS name.

Whatever they called it, the first UMS was simple: Four bands, $5. A young DeVotchka headlined and they nearly sold out a Sunday night at the Bluebird Theater. Each of the bands was paid around $250, which was so unheard of for a local band playing a warm-up spot that one musician tried to give the money back, thinking there’d been a mistake.

By this time, Moore become the theater critic at the Post, and the paper hired Baca to take over the music beat. Baca also became Moore’s right-hand man in organizing the festival.

The show stayed at the Bluebird in 2003 and moved to the Gothic Theatre in 2004, then back to the Bluebird for 2005. The headliners in those years: Planes Mistaken for Stars, Dressy Bessy and Matson Jones.

In 2006, everything would change.

"If you give this up, it will change forever.”

John Moore: I remember meeting. We were drunk and exhausted and sitting at that bar across the street from the Bluebird. This is kicking my ass, you know? And [Baca] is like, "Well you know, if you ever decide this is too much work for you or that you’re done with it, I got some ideas." And I was just like, “Fuck yes. Please."

Ricardo Baca: So I don’t think it went quite that way. I think John ended up at the space where he was done. And so he asked me if I was interested and, you know, I was and I wasn’t? I saw how taxing it was to him every year and it was also so nice to be music critic and have this amazing package and festival produced on your beat by somebody else. And so when he asked if I was up for taking it over, eventually we landed at the right place, but I told him, "If you give this up, it will change forever."

It did. Baca moved the UMS to Baker, where he started out with one day and about 25 bands.

Ricardo Baca: I just knew that was how it was gonna go down. I ran into [then Hi-Dive owner] Matt LaBarge and I was like, "Hey, I’m going to see Black Rebel Motorcycle Club at the Larimer and I have a plus-one, do you wanna come over?" And on the way back we stopped at the shitty Burger King that’s no longer there on Broadway and Speer, and I said, "Hey, I’m thinking about bringing this over to your neighborhood, what do you think?" And he says, "I think it’s a great idea."

That first year was literally inside an art shop that was 300 square feet, inside whatever Mutiny was called at the time, the Hi-Dive, maybe some DJs, not even an after-hours party. And we just kept growing.

John Moore: That was the birth of the UMS.

Ricardo Baca: I remember including DJs for the first time, stand-up comics for the first time, and just embracing everything around us, from trying to throw parties in the random auto gallery and the art gallery and upstairs and downstairs at The Skylark.

Ronnie Crawford, longtime Skylark bartender: We had the upstairs after-hours party and everyone from the clubs and the main people and Ricardo and his crew and the principals from the Denver Post and Greg would show up. That was 2 o’clock to 5 o’clock in the morning. It got to be a meeting of the minds

Ricardo Baca: And then the first after-hours party that Chris Dyer threw for me. And Chris Dyer’s a lunatic. He threw the late night parties at the Denver Film Festival, which are legendary. I called him and said my music festival needs an after-hours party. He threw after-hours parties for five, six years, between the basement at 3 Kings and at The Skylark for years. In fact, Chris Dyer went on after I left to start the Meese party (Centennial Day Party). He did the Meese party for all those years. The Meese brothers and whoever else booked it, and Dyer would bring the party.

“I just came back to the hammock and basically got naked and just lied there in fetal position, just trying to figure out what the fuck just happened.”

Ricardo Baca: The festival was ultimately taken away from me by the Denver Post. There was a concern on the business end initially, once they started seeing big brands attached to the event and they’re like, "Wait a minute. Are we missing out on advertising revenue?"

Greg Moore, former editor in chief, Denver Post: As things get more successful, you start paying attention to them more.

Ricardo Baca: And so a meeting was called. Went in to the meeting and they’re like, "We think we need to own this event because it’s making money now." And I was just like, "Well, one, no. You’re not going to own the event. I own it outright and trust me, I’m not making any money."

And Greg Moore and I went downstairs and he just said, "You know, it’s all about the perception of the conflict of interest and your days at the UMS are over," basically. And that was heartbreaking and to this day one of the most destructive, awful, awful moments of my life.

John Moore: The thing that stuck in my mind -- he said, "You guys are reporters for the Denver Post and for four days of the year, you’re music promoters. And you have to understand how weird that looks on the outside."

Greg Moore: I remember a discussion about, “Hey, we’re the music critic, but we’re also deciding what bands get to play in the UMS.” I think that’s a pretty obvious conflict that you really don’t want to have.

We’ve always sort of said the most important part of a potential conflict of interest is recognizing the potential and not waiting for an event to precipitate the action. We just thought it would be better to sort of move the music critic out of that mix, and I think it was absolutely the right decision. And of course soon after that we ended up putting Rick in charge of the Cannabist, which is the single best decision we made.

Ricardo Baca: Personally, it was the worst thing that’s ever happened to me and the best thing. You can see these jump ropes tied around this pole and that tree? I used to have a hammock there. And when that happened to me, I just came back to the hammock and basically got naked and just lied there in fetal position, just trying to figure out what the fuck just happened and what I was gonna do with my life.

But I think on like the second day of crying I had this weird epiphany where I realized that I had been throwing this party for fucking years and it fucking just killed my summer, and I love summertime. And I think once I realized that, I was like, "Did you just get your summer back?’”

John Moore: Maybe we should make this clear: None of us got our expenses covered. We would have done this fucking thing year-round out of pure love. So to take this thing away -- we’re sitting there going, "Well, who the fuck do you think is going to do this?"

“What I would say is, ‘This is a community event.’”

Ricardo Baca: I remember going into work the next week and telling them straight-up, "I don’t know what the hell you’re doing with this, but you have to let me recommend somebody." I sent them a two-page email extolling the virtues of my volunteer of two years -- top volunteer, the most accountable motherfucker.

Greg Moore: Rick was really, really high on Kendall.

Kendall Smith: When it came time after Ricardo recommended me, I went in, interviewed with a couple people. What I would say is, "This is a community event." And I kept repeating that.

The execs at the paper, they had a choice to make: We can take this and make it a marketing event. We could turn this into something where people who advertise with us have the ability to engage with this demographic and just turn it into something very similar to other events. Or, hey, we've got this foundation that does these great signature events in other areas. And they made the choice to put this into the foundation and let it be a community event and let us not worry about revenue but grow it in a conservative way.

Greg Moore: Kendall was passionate about the UMS, has a business mind and really blew us away putting together a P&L on how we could grow the UMS.

Will Dupree, UMS production manager: When Kendall and I took over the event, all the people who had worked with Rick kind of bailed, and so we didn’t really have that human infrastructure. And so it was like a 10-year-old's soccer game, you know, anytime there’s a problem, everyone kind of runs to the ball.

Kendall Smith: Producing this event is tantamount to standing on a pile of sand. Because you’re dealing with independent artists. You’re dealing with independent business owners. You’re dealing with neighborhoods.

These two are, as Dupree put it, “the only people for whom this is first priority.” Dupree’s responsibilities include overseeing licensing and permitting, community relations, security, the police department, production vendors, cleanup and a volunteer program of 350-400 people.

Will Dupree: I started to create the structure whereby we would identify folks who wanted to be more involved and put them in charge of various areas. And that's worked out really well and we have an incredible group of people. We have people who have been with us five, six, seven years, in these staff positions, which is invaluable because it’s institutional memory.

Kendall Smith: Every year you kind of have to re-fashion.

Will Dupree: Every year we try out new venues and they see how they work. And in some cases it just doesn’t really work. But among the reasons that a business would want to be a UMS venue is to bring people in the door that don’t typically come in with the goal of having them come back at other times, other than the UMS.

Laura Banning, bar manager, The Hornet: Some of these people have never been to The Hornet, which has been here for almost 22 years, so it’s always a welcoming surprise when we meet someone new.

Chia Basinger, owner, Sweet Action: The first few years we were open, UMS was, like, level 15 compared to what we were doing normally. Every year to date it’s been our busiest weekend of the year. It’s people all over the place, it’s always hot, people want ice cream. It tends to be harder for the retail places.

Marty Levine, president, Broadway Merchants association: I have a hard time saying as a whole group that the Merchants Association is all-in for the events.

Kendall Smith: There are businesses that aren't going to do well during that weekend. Lee Alex furniture, they didn’t enjoy UMS because people aren’t furniture shopping, but they could tolerate it for a weekend because they realized all their business neighbors were crushing it.

Laura Banning: I think when people think of Broadway, they think it's eclectic and fun. And when UMS rolls in, it’s amplified in the best way. It's like a giant block party.

Chia Basinger: The organizers at the UMS have always been really good about working with the businesses and trying to make things better for the people around Broadway. By and large there’s been a good relationship with people on the street. They’ve been great partners.

“Our kind of first priority has been to stay in the neighborhood.”

Will Dupree: My perception was that we were kind of on the bubble with the neighborhood when Kendall and I took over.

Kendall Smith: We attend every neighborhood meeting. We attend every merchants meeting.

Will Dupree: We have two neighborhoods: Baker to the west of Broadway and West Wash Park to the east of Broadway. There’s also a merchants association along Broadway. They all meet once a month and I go almost every month to each one of those meetings, even when I don’t really have anything to present.

Loretta Koehler, Baker Historic Neighborhood Association board member, 18-year resident: They offered free tickets to those of us who were close to the main stage, so we ended up taking advantage of that. Now we’ve gone down to half-price.

When Illegal Pete’s became a venue, one neighbor said, “I could feel my house rocking.” And she will actually leave town because she doesn’t want to deal with it.

Sherri Way, president, West Wash Park Neighborhood Association: [Dupree] has tried to work collegially with the association and the residents to understand in advance what the problems might be and mitigate them. He’s also good at staying in touch and circling back to see if there were any problems. Not everyone’s going to like it because big events are disruptive.

Marty Levine: They worry about some of the riff-raff that might show up or the destruction of property. But they’re good about cleaning up afterward. Will, he’s very good. He comes to our meetings even when he doesn’t have to. He’s trying to be part of the neighborhood. The UMS has kind of embedded in here over the years.

Will Dupree: People are concerned about parking, they’re concerned about noise, they're concerned about public behavior, and so we took account of all those things and explored ways that we could address those issues and went back and reported to them and said, "Here’s what we’re doing." When there were things that we couldn’t really address, we just told them we can’t really resolve this issue.

Kendall Smith: We were met with skepticism early, but I think they realized pretty quickly that we’re gonna be honest, we’re gonna try our best, and if we fail on stuff, we’ll own it. If we do good on stuff, we’ll own it.

Loretta Koehler: Will has been really good about coming to the neighborhood meetings and trying to work with the neighborhood. We had issues with people, like, parking their bikes on a post near our house, but they’ve been pretty good about addressing issues.

Sherri Way: Broadway -- it’s a hard location to do this. And as the showcase grows, that becomes challenging and I don’t know what kinds of things will flow from that. I personally haven’t heard any complaints from the showcase last year.

Will Dupree: The other thing about going month in and month out is that you build relationships with people. A big part of the community relations effort is for people to have a name and a face -- it's not just this amorphous thing that’s going on.

Loretta Koehler: Because we know him from neighborhood meetings, it’s nice to be able to put a name to a face.

Will Dupree: And at a certain point you stop being “them” and you start being “us.”

Kendall Smith: Will was at an event talking to David Moke (director of programming for the Denver Theatre District) and when he’s in these city meetings, the UMS is often brought up as an event that knows how to integrate with a neighborhood, knows how to function in a way that can ensure that whether they’re welcome or not, they can continue to operate.

Will Dupree: Our kind of first priority has been to stay in the neighborhood. I could be wrong, but my impression is that South Broadway was where people went to see local music longer than any of these other places. And the character of our event is so interwoven with that. It’s not that we couldn’t do it someplace else, but if we did it someplace else, it would change the nature of it.

Matty Clark, co-owner, Hi-Dive, guitarist, Zebroids: Since the Dive opened in 2003, it has been a hub for local music. You can't really talk about the UMS without talking about the Hi-Dive.

Ronnie Crawford: If they take it out of our neighborhood, it just won’t be the same. There’ll be food trucks. I hope that the principles in all this are not thinking about that. Because there’s nothing like South Broadway.

Marty Kilorin, co-owner, 3 Kings: We’re extremely proud of the neighborhood. We’re a great place for live music. If you don’t like what 3 Kings has, you might like what the Hi-Dive has. So it makes sense to have a music festival to have different venues to go to. It’s great exposure, not only for the the bands but for the venues.

“It’s kind of the summer reunion for the local music scene.”

Kendall Smith: The whole mission for me, coming in, was let's grow the audience for these local bands and how can we do that.

Will Dupree: My whole reason for getting involved was, I wanted to help build an audience for the local music scene. The challenge is -- how do you crack it? You see a list of bands, you’ve never heard of any of these people, and not that many people are gonna start googling band names. So a festival setting creates a great opportunity. You’re probably not gonna like everything because everyone has their own taste, but I think that chances are pretty much 100 percent that you’re gonna come away from the event as a fan of someone you had not heard of.

Ricardo Baca: I got off on those early years by, like, asking friends to play solo. And there might be five people there, there might be 50. Isaac Slade of The Fray stopped by at the peak of their popularity to play with his buddy Patrick Meese at one of those solo shows. I asked Patrick to play -- at the time he was with Meese, now he's with the Night Sweats.

John Moore: That was crazy because it was -- what was the name of that shop?

Ricardo Baca: It was Kozo. Kozo Art Supply.

John Moore: Yeah, it was like an art supply store, and Patrick’s just sitting there playing his acoustic stuff and Isaac’s just there to watch him and people are just cajoling him on. And this is, like, at the beginning of when The Fray was the big deal and just to see him picking up a guitar, so you’re seeing Patrick Meese and Isaac Slade in and art supply store, it was amazing.

Though people have been reluctant to discuss it with journalists, both now and in the past, there has been some opposition to the UMS in recent years. Mutiny Information Cafe owner Jim Norris started throwing a non-UMS show in the middle of the UMS. And in 2014, some musicians distanced themselves after they were asked to play for festival wristbands (instead of money) in 2014 -- a policy the UMS abandoned the next year.

Josiah Hesse, editor in chief, Suspect press: Especially around that time, with Denver just starting to really feel the extreme effects of gentrification -- especially in the art scene -- people were frustrated that the compensation for performing at UMS was going down for the local bands and then at the same time more of that was being invested in getting larger acts for the main stage.

I think they did kind of learn some things from the mistake of that year and change course.

This year they have Esmé as one of the headliners, and you can’t get more Denver-underground-music-scene-success-story than Esmé Patterson.

Ronnie Crawford: There’s nothing like it around to highlight up-and-coming bands. It’s a great jumping off place.

Marty Kilorin: The beauty of it is that it does concentrate mostly local acts and you’re getting everything Denver has to offer in one stretch. That’s why I think it’s so spectacular, and it makes me proud to see so many Denver music fans to show up to support the local bands.

I came in early on a Sunday morning to open the bar and the stage was a disaster, the bar was a disaster, there were ceiling tiles hanging down, there was glass everywhere, there was confetti everywhere, we had to fix the sign behind the stage. I asked my partner what the hell happened and he said, “Dude, there was rock show here last night.”

Matty Clark: I could regale you with the time I ate mushrooms with A Tom Collins in Nathaniel Rateliff's pool before setting off a boatload of illegal fireworks in the middle of Broadway during a Dirty Few set, or the impromptu 1 a.m. Sunday Zebroids set in 2012 where we played on the floor and whipped the crowd into the most violent and beer-soaked sweaty mass ever, but my favorite UMS moment ever is probably UMS 2007. I was brand new at the Hi-Dive and Sputnik, and didn't really know any of my co-workers or many of the regulars. Hot IQs and Born in the Flood closed out the night and people were finally opening up to me. We were getting our asses kicked at Sputnik. Bill Murphy from the Swayback was so drunk behind the bar he straight-up fell over. And in that moment I looked around and realized I was home.

Scotty Saunders, Instant Empire: We've played UMS five times out of the last six years. This year will be our sixth. I think when we first started playing, we were just really happy to be included in the scene. Now, it's really all about hearing lots of new bands and catching back up with friends we've made over the years in various bands.

Esmé Patterson: The best part of the UMS for me is discovering new bands or discovering new work by old bands that I’ve loved.

Anna Smith, Ancient Elk: For us it's been about the fact that it's the one time in the year every musician in Denver are all in one place. It's such a tingly feeling walking down Broadway and ending up hanging with music buddies you might not get to see often.

Will Dupree: It’s kind of the summer reunion for the local music scene.

Esmé Patterson: You’d be running from one part of South Broadway to another and you’d see 500 people that you know, and you’re walking down the street hugging each person. You see every person you’ve ever met.

Matty Clark: At the heart of it, what the public doesn't see, is that the UMS isn't about sponsors or touring acts or anything like that -- it's about all these bands gathered together to just hang out with each other for four days. Our scene is so thriving that on any given night there are multiple shows around town and it's hard to go support or see your friends bands. UMS brings us together in our favorite places up and down Broadway and allows us all to commune together.

John Moore: Nothing compares to the UMS for the time when the bands are bonded. I think there is a real sense of community within the local music community and a big part of that is that for four days of every July, you’re hanging with people that you wouldn’t otherwise. The community that it builds and the love that it creates and the music that goes out into the universe because there is a festival -- it’s a great thing.

This year's UMS is happening Thursday through Sunday, July 27-30. Four-day passes are $55 in advance and $75 on site.