"I remember when 46th was a dirt road, and Pecos going north was a dirt road. There were dairy farms there, in my lifetime. So I’ve watched progress. This is beyond progress -- this is greed."

-- Sid Quintana, lifelong Northside resident

"I worry that the conversation will lead people to think that the solutions will be to stop improving minority neighborhoods, and I believe that’s racist."

-- John Hayden, president of the Curtis Park Neighbors and "classic gentrifier"

"I went to Stanford. I am bougie. I like having a good walking score. I like having places to eat with good, clean food. Natural Grocers just went in. Of course I like this. ... It's cool to have everything at your fingertips, and then your cousin has to leave their house, and your aunt is afraid they're going take away her sunshine. 'M'ija, they're going to take away my sunshine.' Let that sit in your chest."

-- Eutimia Cruz Montoya, Five Points native, ancestral medicine practitioner

"I think it’s generally positive, but if you ask some people, they would absolutely see it as a negative, and we, not just me, need to hear from them and see if there are ways to adapt."

-- Paul Books, president Palisade Partners

"The labor market and economic growth could be stymied if you don’t have a diverse population living in your city."

-- Diana Elliott, senior research associate with the Urban Institute

"The hipster guy on his bike wanting to live urban isn’t the problem. The problem is there isn’t corresponding investment in housing, in green infrastructure, in transit, in having some limitations on urban sprawl so the market isn’t just spiraling out of control. They basically have people pick up the pieces and wonder what happened. It’s the failure of the political and business establishment to invest in things that are going to have long-term social value."

-- Kyle Zeppelin, developer

"The family structure and the dynamics are affected. Everyone is thinking about money, and that's not what's most important. It's almost like being a refugee."

-- Rey G., a fourth-generation Globeville resident

"As a kid who grew up north Philadelphia, in a Latino section of north Philadelphia that was not subject to change, that didn’t have amenities, basic amenities like access to grocery stores, access to jobs, to health services, that’s the downside -- not having the opportunity to make investments, private and public investments, to spur change. So where we find that balancing act between making public and private investments that bring about change to neighborhoods to add amenities while preserving affordability for the residents who have been there a long time, that is the work the administration is looking to do. ... So where do you find that balance? It’s not something you can turn off. You can’t stop people coming to the city."

-- Erik Soliván, director of the Office of HOPE, responsible for coordinating Denver's housing policy

"My whole vision was that I was going to come home and buy a home in the Five Points. But I couldn't. I was totally priced out. There wasn't a job I could get that would allow me to do that. I was really salty about it. Watching the process for all my friends and family members and watching literally everyone in my family relocate, it just hurt. It was a hurt that was really deep and really unsettling."

-- Asia Dorsey, Five Points native and owner of Five Points Fermentation

"They want to feel that sense of community. They want to know that cashier at the Safeway. They want to know where the best pan in the 'hood is. They invaded this, and they’re looking for it, they want it, and so they’re pushing, pushing, pushing. Meanwhile, they’re stepping over everybody. The community that you were looking for, you’re suffocating it, you’re drowning it, it’s gone."

-- Ambrose Cruz, lifelong Northside resident, United Northside Neighbors

When I tell Ambrose Cruz about the question I'm trying to answer -- what's so bad about gentrification? -- he gives a bitter laugh, but he agrees to show me around his neighborhood. Cruz grew up, as did his parents and grandparents, in what was then the Northside and is now called Highland by many. He is an officer in United Northside Neighbors and a fixture at Denver City Council meetings when properties in the area come up for rezoning. I have some idea already of how he feels, which is why I approached him in the first place. He suggests we meet at the corner of Tejon Street and 30th Avenue, near Little Man Ice Cream, and he tells me why he'll never eat ice cream there.

"I went to my first funeral here," he says. "I was 11 years old. My friend, he was 16. He had a heart tumor. First funeral, bunch of kids. I would never set foot in that place again."

The complex that holds Little Man Ice Cream was Olinger mortuary before being redeveloped into shops and restaurants. On summer nights, there are concerts in the courtyard and people dancing to live music. I have been there myself, waiting in a line that stretches around the block for delicious but expensive ice cream.

"This was the heart right here," Cruz says. "It was because of death. People died, and this is where we came to put them down. There was loss, but there was community. Their last memories of their family member might be there."

We've written a lot about gentrification here at Denverite, and there's this underlying assumption in a lot of that writing that gentrification is bad -- or at least fraught. But we also write about the latest bar and restaurant openings and fancy new ice cream and high-priced developments coming online.

So when a reader submitted this question -- "What's so bad about gentrification?" -- I thought it was worth taking seriously, even though it caused many of the long-time residents I interviewed to laugh, like Cruz did, or sigh with a patience that is wearing thin.

In many ways, Denver is doing well. During the Great Recession, the city cut services, furloughed employees and struggled to maintain an adequate rainy day fund. But now -- and for several years running -- Denver is adding employees, expanding services from recycling and composting to library and rec center hours and planning for massive infrastructure investments made possible by rising property values. The city expects to end this year with more than 20 percent of its revenue unspent and maintains a 15 percent budget reserve without breaking a sweat. Unemployment is among the lowest in the country, and hundreds of people move here every month.

What could be wrong with that?

Displacement.

That's the one-word answer to "What's so bad about gentrification?" People who called this city home for generations can't afford it anymore and are decamping for Aurora and Thornton and places much further afield. But that one word doesn't really evoke the human costs described to me in interviews with more than a dozen people. Those who remain feel like outsiders in their own communities -- looked at with suspicion by people who moved in just a few years ago. There's a loss of cultural diversity and a rending of the social fabric of these communities and the city as a whole.

Asia Dorsey describes an almost idyllic childhood in Five Points.

Her grandmother worked in property management and arranged it so all her aunts and cousins lived within blocks of each other. Her grandmother would send her down to Aces Grocery, a small family-owned grocery that she still dreams about. The love of food that would become her life's work -- Dorsey owns Five Points Fermentation -- was planted there.

There was the Black Arts Festival and Juneteenth, "beautiful, sparkly ladies throwing candy at you."

"It was a really, really beautiful upbringing," she says. "I felt really safe and really protected. Everyone knew my grandmother, and I had a lot of freedom. I roamed all over."

There are darker memories of violence, as well, but Dorsey, now 27, was a young girl in the mid-90s when things were at their worst, not just in Denver but in large cities around the country. Her mother later moved the family out of the neighborhood because she wanted Dorsey to go to different schools but Dorsey always maintained the hope of returning to Five Points, and it remained the center of her extended family.

Dorsey went away to college; she planned to become an environmental lawyer and got deeply involved in activism in New York City. Living in New York wore her down, though, and one of the few moments of joy she recalls from those years came from a class called "Agriculture in the 20th Century."

She scrapped law school and went to Australia to study permaculture and later traveled to Ghana and India and New Zealand, learning all along the way.

"Fermentation showed up for me because I wanted to heal the depression I found in New York, and I did it with sauerkraut and bone broth," she says. And from there, she decided to see if she could implement her ideals about food and economics in a successful business.

"I wanted to bring probiotics to the people. I wanted to bring all my passion," she says. "And I studied Marxism in college. I studied economics but from the other side. I never imagined I would be in business."

She actually wrangled the name Five Points Fermentation from the original owner, who wasn't doing much with it and who had no connection to the community. She tries as much as possible to do her business in Five Points and spend time there.

But she doesn't live there and neither do any of the aunts and cousins who made her childhood so magical. Dorsey has an apartment in Sloan's Lake because that's where she can afford to live, while other family members are in Northeast Park Hill, Green Valley Ranch and Aurora.

As much as she still loves Five Points, it's not the same.

"It's not like you can go visit your auntie and get something to eat," she says.

Dorsey sees this wave of demographic change as different from previous changes. Cities are fluid, dynamic places, and Five Points has always been diverse.

"We had so many immigrants, Jewish people, African-American people. When we had a new iteration of people, they didn't try to erase what was there before. These communities are ecosystems, and they have rules and they have norms. You have the ecosystem model, and you have the imperialism model," she says.

The use of new names like RiNo for the section of Five Points near Brighton Boulevard are part of the new approach. It's galling, Dorsey says, that people want "to take whole sections of what used to be the Five Points and rename it and have that cultural history not honored."

In Dorsey's view, the newcomers are losing something, too.

"It's the Starbucksification of communities," she says. "I don't admire the struggle that middle-class people live, and I don't think it's better than the lifestyle that lower-income people live.

"We were broke, and my life was beautiful."

There's a reason certain Denver neighborhoods are vulnerable to gentrification.

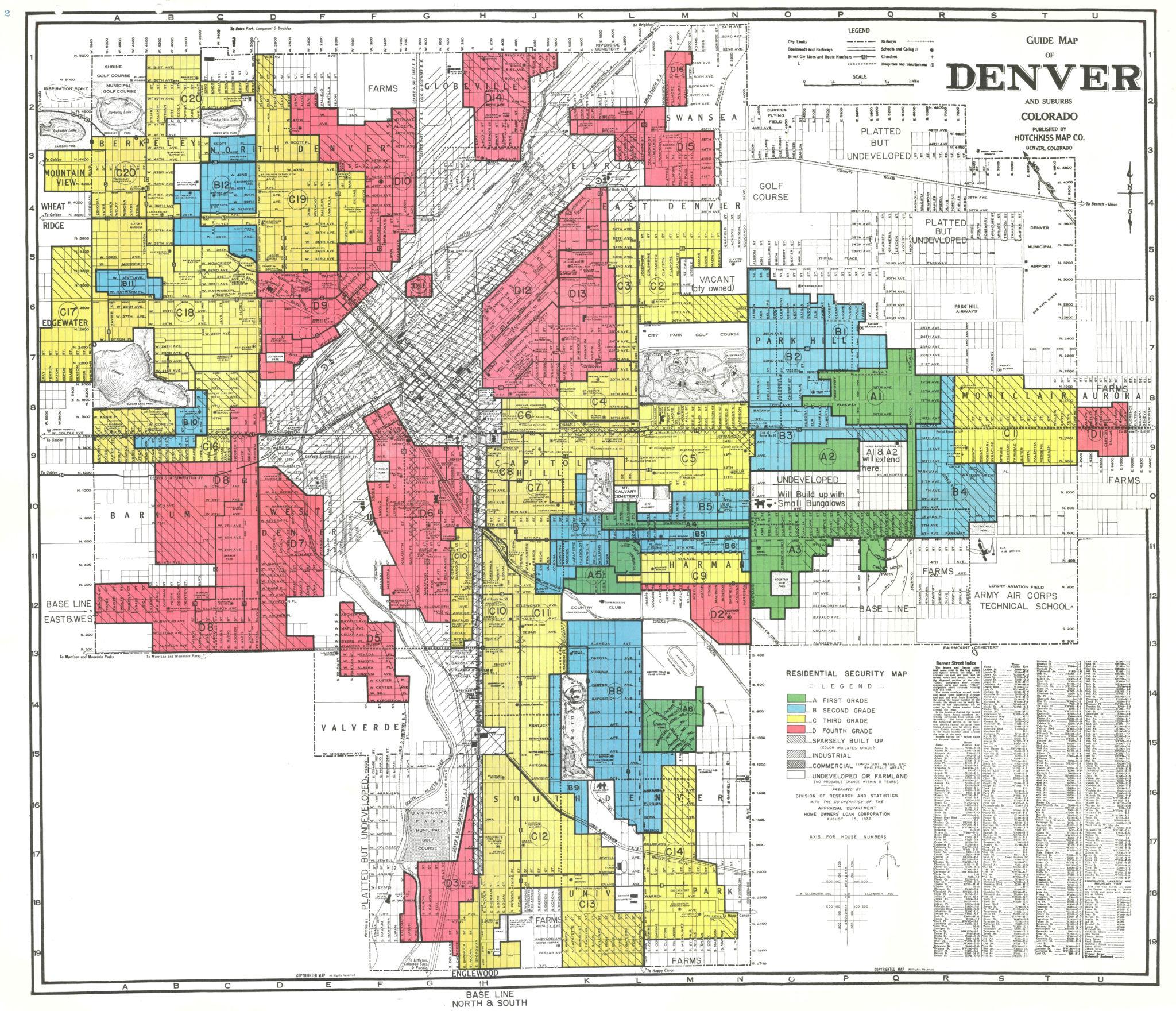

It goes back long before the current building boom to the lending practices codified by the federal government decades ago. Residential Security Maps, which determined where people could get mortgages, favored white areas over areas where black and brown people lived. This practice undercut the ability of people of color to buy homes and build wealth. This legacy, along with white flight, ongoing school segregation and the devastating impact of first heroin and then crack on urban neighborhoods, is what created blocks and blocks of centrally located historic homes that could be bought at rock-bottom prices.

This 1934 Residential Security Map shows Five Points, Highland and my own neighborhood of Baker in red or yellow. You couldn't get a mortgage in the red areas, while yellow and to a lesser extent blue meant lenders should be cautious.

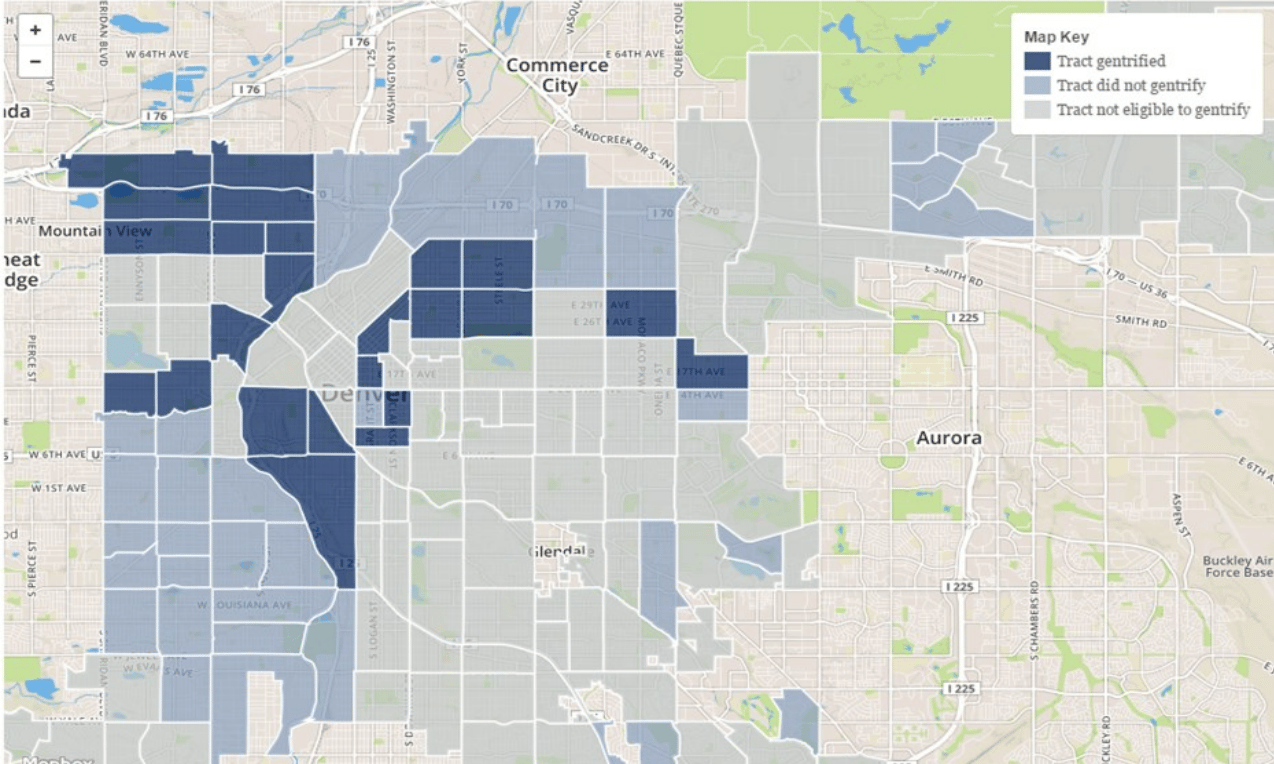

This map lines up well with the areas that have gentrified already in Denver, as well as those considered vulnerable to gentrification because their residents have lower than median income and are more likely to be burdened by the cost of housing.

I will raise my hand and admit to being a gentrifier in some senses.

Baker had already changed a lot by the time I moved there in 2009, but as a middle-class, college-educated white person who grew up in a small town and pursued urban living as an adult -- and who could afford to do so because of decades of social and economic policy that preceded me -- I am part of this demographic change transforming Denver.

My neighborhood has continued to change in the eight years I have lived there. My son looks at the mid-rise apartments going up along South Broadway and laments that you used to be able to tell where you were but now everything looks the same. The landmark he's missing is the now-demolished Gates Rubber factory, which once employed hundreds but had since become an eyesore and an environmental hazard. The historic homes that once housed struggling musicians, with their peeling paint, bare dirt yards and porches littered with cigarette butts and empties of PBR, are being returned to single-family status, with bright new paint jobs and fresh grass and glider bikes in the yard.

Maybe I should be happy about this -- my house is worth much more than I paid for it -- but I miss the more eclectic version of the neighborhood that I moved into. And U.S. Census and American Community Survey data confirm what I suspected: Baker's Hispanic and Latino population fell from 54 percent in 2000 to 34 percent in 2015. Nothing about Denver in 2017 makes me think that trend will reverse or even stabilize. I grew up in a small town where homogeneity produced an oppressive conformity. I didn't move to a city so that I could raise my own kids in a world of sameness -- even if I do enjoy fancy ice cream from time to time.

Ambrose Cruz remembers the first white person he met in his neighborhood.

This is not quite right, he clarifies. There were always white people on the Northside -- Italian and Polish immigrants. His uncle, Sid Quintana, recalls his best childhood friend by the very English name of Bevington. But Matthew was the first of a new kind of white person, the kind who wears cargo shorts. He met Matthew in a bar on Tennyson and found out he'd moved into a new condo across from The Conflict Center on Tejon Street, condos that must have gone up in three days or something because Cruz had no idea anything was afoot.

Twelve years later, the geography of Highland is a map of loss. Quintana and Cruz walk up Tejon Street listing the last names of the families that are gone, the addresses of the houses that are gone, the businesses and social service agencies that are gone. In 2000, Highland was 67 percent Hispanic; today, it's 27 percent. Cranes are everywhere, and the noise of construction makes it hard to talk at times.

"You know there is one spot to find menudo around here? That’s probably one of my biggest issues with the whole fucking thing," Cruz jokes. "One spot to find menudo. You gotta go up to Sheridan now."

At one point, we pause in front of a real estate office, and Quintana taps on a picture of a gorgeously restored Victorian listed for $1.6 million.

"That was my first bedroom window," he says of a second-floor vantage point. "I was just out of high school and working as an X-ray tech at Denver General."

Quintana has suffered a slew of health problems and had several strokes. He's recently had open heart surgery, and he walks slowly. He says he grew up in a community where people helped each other out, where you didn't have to worry about a young child or an elderly relative wandering off because they would be found right away by someone who knew them. Now people lay on their horns because he's not crossing the street fast enough for their tastes.

Cruz doesn't use the word gentrification, but "communicide."

"All these people moving in, I always wonder: What was wrong with your community? What was wrong with where you grew up?" Cruz says. "I don’t care if you come from Englewood, from New Jersey, from Texas, what was wrong with where you were that you had to go in and literally displace someone else?

"You moved here. Remember that. I’ve been here. What was wrong with your community? Oh, I’m sorry you didn’t have a panaderia. I’m sorry you didn’t have a grocery store up the block. Maybe you should have talked to your city council and dealt with that instead of coming into our community and messing it all up and then going to our city council and complaining because you don’t like what’s here.

"You got mad because you had to leave your community to find the goodness, and the goodness was here, and you destroyed it. Where is it at now?"

It was the architect who first raised the possibility of working in Five Points.

Palisade Partners sees itself as a development group that "looks for opportunity where others aren’t or when others aren’t." In 2013, the architect who had worked with Palisade on apartment renovations and townhouse projects brought up the idea of doing a project at the site of the former Phyllis Wheatley YWCA, 2460 Welton St. The Wheatley is now 82 apartments, 14 townhouses and 3,800 square feet of retail. The Lydian is under construction at 2560 Welton St. and expected to bring eight stories and 129 units later this year. And Palisade recently purchased the historic Rossonian Hotel and is assembling adjacent parcels to support a larger redevelopment project. That project will preserve and repurpose the landmarked hotel, once the center of Denver's jazz scene.

Palisade does not work exclusively in Five Points, but president Paul Books has become deeply involved in the development of the neighborhood, including serving on the board of the Five Points Business District. He first became aware of the area when he took a tour as part of the University of Denver real estate program in which he was studying, and he still encounters people who are surprised he's working in Five Points, two decades after the light rail went in and Coors Field went up.

"For someone who didn’t know Five Points, when you tell people you’re doing a project in Five Points, they’re like, 'What? The same Five Points I grew up with?' Or whatever. There is this stigma, this nervousness about it," he says. "We started looking at it because we knew nothing had happened for a while. We didn't exactly know why."

In our conversation, Books uses this word "stigma" a few times to describe how some outsiders view Five Points. He doesn't explicitly name this as racial prejudice, but it hangs in the air. There are also practical challenges to developing here. The light rail, one of the amenities that makes Five Points so appealing to newcomers, touted in every real estate listing, creates access and spacing issues for new buildings on Welton. (Dorsey describes the construction of the light rail as an event that "broke the heart of Five Points.")

Books is aware that he is working in an area with a storied history, and he wants to respect that. For the Wheatley project, he sought out the stories of now-quite-elderly women who lived in the YWCA and featured them in the lobby of the building. And he kept the name, which belongs to this nation's first African-American female poet, a freed slave who published her first work at 14.

Five Points is considered an urban renewal area, and projects are eligible for public financing to fill in the gaps that private lenders won't cover. There's also a cultural-historical district with design guidelines. All of this means the city and the neighborhood have more say about what development looks like along Welton, when compared to other parts of Denver. There are African-American business owners and property owners who are bullish on development, who see opportunity and revitalization, who want market-rate housing here, not more affordable housing.

Books knows the community is divided, with long-time residents who are renters the most vulnerable and the most unhappy with change. He wants to be a positive force in the neighborhood.

"I’m not saying we’re perfect, we continue to strive to be better, but it’s a cool blueprint with the landmark district so you end up with good design and with the TIF district so you can help end up with projects of high quality with some of these mixed-income opportunities, and then still provide those neighborhood services through the commercial spaces and activation," he says.

Books said he's being conscientious as he considers tenants for the first floors of his buildings. He probably wouldn't sign a "fine dining" restaurant, for example, but would hold out for a restaurant serving good quality good at a price point and in an environment that is "comfortable and inclusive."

When I ask Books if his projects may inevitably contribute to further demographic change in Five Points, he pauses for a long time before answering.

"It may be too soon to totally tell. We’re definitely watching. We still have the next projects," he says. "... Maybe I’m biased, but I do look at it as a net positive. But there is a segment that are renters or who grew up here and see it changing, that don’t like it."

Books has one more thing to say that will be hard to take for some people unhappy with change in Denver.

"Gentrification, not just gentrification but growth and how it affects apartment rents in the city of Denver, I’ll say this: The solution is in the problem," he says. "Unless you stop people from moving here, you get more people, you increase demand and supply is not keeping up. Development then creates this change that creates gentrification, but now housing is unattainable for people, but the only way to make it attainable is more supply."

There was something wrong with where John Hayden was from that he couldn't fix by going to his city council.

Hayden left Arvada for Amherst College in Massachusetts in the late 1980s and found himself surrounded by people who grew up in New York City and other large, diverse East Coast cities.

"I realized very quickly they were light years ahead of me in terms of their exposure to different people," he says. "They had benefited greatly from the fact that they had grown up in a diverse city. When I came home, I wanted to live in a diverse place.

"Part of that had to do with the fact that I was gay, and in 1992, returning to the suburbs of Arvada was not a thing you wanted to do if you were gay. The city was a place that I would feel more welcomed and safe."

This decision has worked out well for Hayden.

"We were the classic gentrifiers, the gay couple without kids. We didn’t care about the schools. The neighborhood was wonderful for us," he says. "It was an urban setting with affordable housing that we could work on and build a life and build wealth from. That dynamic existed for us because the neighborhood had been weakened to the point that the existing population was leaving in droves. The housing was affordable, and the schools were terrible."

Hayden is the president of Curtis Park Neighbors and a real estate agent who helps people buy and sell houses every day, including in Five Points. He says concerns about the quality of schools are still the major reason cited by families with children who want to leave the neighborhood, and that concern extends across all racial groups.

Five Points' population fell from 32,000 in the 1950s to just 8,000 in 2000, and it's now up above 14,000. Hayden sees the racial segregation that created these communities and then undermined them as the real enemy, and he's deeply concerned about a narrative he sees around improvements in majority-minority communities, that better sidewalks and bike lanes and rec centers are a tool of gentrification.

Poverty itself is destabilizing, and across the country, poor neighborhoods see higher rates of displacement and turnover than middle-class ones.

"I think that’s missed, and it’s kind of a racist assumption that it’s just white people who want good schools and good parks," he says. "'Oh, the minorities will just stay and go to those schools.' They won’t, and they don’t."

Hayden describes the process of gentrification as one that has made Denver neighborhoods more diverse, not less, as white people move into areas that were once majority black or Latino. If that was true at one point, we appear to have passed the threshold. Five Points in 2000 was 26 percent African-American and 43 percent Latino; today it's 10 percent African-American and 21 percent Latino -- making the neighborhood about as black as the city as a whole, as well as more white and less Latino. Hayden describes Five Points as "as diverse as the rest of Denver -- and Denver would benefit greatly from increasing its diversity."

While market-rate housing in Five Points has become quite expensive, the neighborhood retains a large share of subsidized affordable housing. The solution, Hayden says, is not to build more affordable housing in Five Points but to build more in every neighborhood in Denver, as well as ensuring that every neighborhood has the walkability and transit access to downtown that makes Five Points so desirable. That would take some of the pressure off.

The entire city will be worse off, though, if it doesn't have children and multi-generational families.

"That young families can’t afford to live in the neighborhood to a great extent is really unfortunate," he says. "That is a sad change that has happened. I have lots and lots of clients who would like to live in Five Points who can’t. And that’s white, African-American, Latino.

"That said, I do not know any homeowners who are going to put their house on the market for below-market so those people can live here."

The problem of gentrification is not just about how people feel about their communities.

Or what they look like or how fancy the restaurants are.

Diana Elliot has been studying the loss of housing accessible to low- and moderate-income people in cities like Denver, Miami and Austin for the Urban Institute. The high price of housing has serious implications for the economic vitality of the region, and it's been flagged in recent economic forecasts as a drag on growth. Companies can't attract workers because housing costs so much, and companies can't grow because they can't hire enough workers.

"The way we’ve had these conversations in each of these cities, especially with business leaders, they are critically aware that this can create labor market problems not just now but into the future," she says. "Look at the occupations of low- to middle-income workers. They are the support occupations that keep a city going -- managers, accountants, teachers, customer service reps, registered nurses, sales people -- these are all occupations that are necessary to keep a city going. You can’t just have people in your city who work in really high-income occupations."

As low- and middle-income workers move further and further out in search of affordable housing, they increasingly take jobs in those communities, rather than commute into the city center.

City officials say they take all of these concerns seriously, and they're developing policies that they believe will help. Mayor Michael Hancock has long touted the benefits of economic growth and asserted that this growth can and will benefit all residents. But in an interview after this year's state of the city address, Hancock said the city is losing the "people who helped build a community and create a sense of community."

"You start to see the loss of historic and special places that made a neighborhood unique," he says. "We lose the soul of our city or at least those areas of town, and when those things are threatened, you begin to lose a little bit of who you are as a city. When people make that decision to move on, that's one thing, but when people are forced out, that's when gentrification becomes a real challenge."

Erik Soliván, director of the Office of HOPE and the man charged with creating more effective housing policy for the city of Denver, grew up poor -- just as Hancock did -- and did not see reinvestment come to his part of north Philadelphia. That's not what Denver should want, he stresses. "Balance" is a word that Soliván uses a lot.

Last year, the city released a report that identified neighborhoods vulnerable to gentrification and specifically to displacement, and its new housing plan includes policies to target housing assistance in the form of eviction prevention, property tax rebates, subsidized home repairs, job training, small business support and financial literacy programs to those areas. Making Denver work for everyone isn't just a platitude, Soliván says, but a value city officials are enacting through policy.

Community activist Candi CdeBaca says city leaders have a very difficult time conceiving of true community reinvestment. What Denver really needs is community land trusts to preserve housing for long-time residents. That would create some confidence that they would get to enjoy the new sidewalks and rec centers.

Millete Birhanemaskel, who owns the Whittier Cafe coffee shop on East 25th Street and strives to make it as comfortable for black activists as for newer white residents, gets frustrated that the response to gentrification and displacement so often focuses on subsidized affordable housing. What discrimination took from black and brown people was the opportunity to own property and build wealth.

"What's affordable housing?" she asks. "That's not the same as homeownership."

Whittier was a neighborhood that her Ethiopian immigrant parents did not let her hang out in when she was a teenager, but it was also a place where African-Americans built a community in the face of discrimination.

"There is a sense of people who just moved to the city being like, 'It's mine,'" she says. "And some of them are our customers."

Cruz, of United Northside Neighbors, has read the reports and been to the meetings, and if the city's strategy is really to support good-paying jobs for everyone, he wonders why warehouse areas have been rezoned for luxury housing. Where were the low-interest loans for small businesses 20 years ago, when it might have changed the trajectory?

"People could have had good jobs in the communities where they live and bought houses and be retiring now," he says.

Eutimia Cruz Montoya goes back and forth on whether she should stay.

Montoya came back to Denver because she wanted to serve her community. She lives and runs an integrative wellness and ancestral medicine practice from the home her grandparents owned on Champa Street in the Curtis Park section of Five Points. Her aunts live nearby on Curtis Street, and when she was 9, her mother bought a home in the adjoining Cole neighborhood. Five Points has been her home her entire life.

Growing up, she wasn't allowed to hang out on street corners. There was gang activity, and she sometimes heard gunshots. Her mother traces the problems in the neighborhood to the Vietnam War and the heroin addiction and PTSD that too many young men from the area, drafted at disproportionate rates compared to their white peers, brought back from the war. It swept through the neighborhood "like wildfire" and took down entire families, setting the stage for the rise of gangs in the 1980s.

"I never felt unsafe, but I was also one of the good ones whose mother was not a drug addict," she says. "We were from, as my mother said, simple farming people, and my mother really embraced her indigeniety through the Civil Rights Movement."

While some of her peers were drinking at football games (in case it needs to be said, an activity hardly limited to low-income neighborhoods), Montoya was going to solstice celebrations with her family and had her mind focused on her studies.

"There were people from among my peers who ended up not in a good way," she says.

In 2002, Montoya left for Stanford, where she studied anthropology. She returned to Denver in 2006 after the death of grandmother, then went to San Francisco. But finding herself homesick, she returned to Denver for good in 2008 and finished her education in traditional Chinese medicine in Boulder. All this time, new businesses and new people were moving into the neighborhood.

"The last year or two, it's been like a punch in the face," she says.

Montoya chooses her words carefully. The problem isn't white people as individuals but an enforced and violent homogeneity that she believes has its roots in the persecution of traditional medicine women in Europe hundreds of years ago.

"There's a good old boy thing," she says. "You either fit in or you don't. You're an engineer or a corporate person or you're a throw-away. That feeling is very present. ... This looks like not saying hi to people on the street. This looks like stopping in front of my grandmother's house and sizing it up. 'Oh, it can't be more than $500,000.'"

Some days she wants to dig in her heels and stay forever as a form of resistance. Other days she wonders if she should give in and sell and be done with it. It's not that there are no positive aspects to the changes, but they come at such a high price.

"People are like, oh, the walking score has improved. But for whom? Black and brown people aren't able to live here anymore," Montoya says.

She recalls visiting Greenwich Village in New York City in 2006 and thinking, "Oh my gosh, this is so cute."

"But they were doing to that neighborhood what's being done to this neighborhood. And they are we."

Montoya doesn't want to come across as too angry. She says she wants to "call in" rather than "call out" white people.

"We all want a better world for ourselves and our children. So, say hi to each other. We can't change the fact that all of this is happening. This has been in the works for 30 years, ever since Coors Field went up," she says. "Take some time to say hello and ask about the place that we're in, and then maybe we all won't be so angry.

"I really want everyone to heal, or I wouldn't do the work that I do."