A proposal to outlaw smoking and vaping on the 16th Street Mall produced both strong criticism and strong support at a meeting on Wednesday morning.

On one hand, health experts, business leaders and Council President Albus Brooks said that the ban could make one of Denver's busiest pedestrian areas more pleasant by reducing secondhand smoke and vapor.

On the other, some council members were concerned that the law might disproportionately affect people who are homeless and that it could push smokers onto other downtown streets instead.

The city's housing and safety committee ultimately sent the ordinance to the full Denver City Council, but not without some serious consternation.

"First and foremost, this is about the health and wellness of the city and county of Denver," said Brooks as he introduced the ordinance.

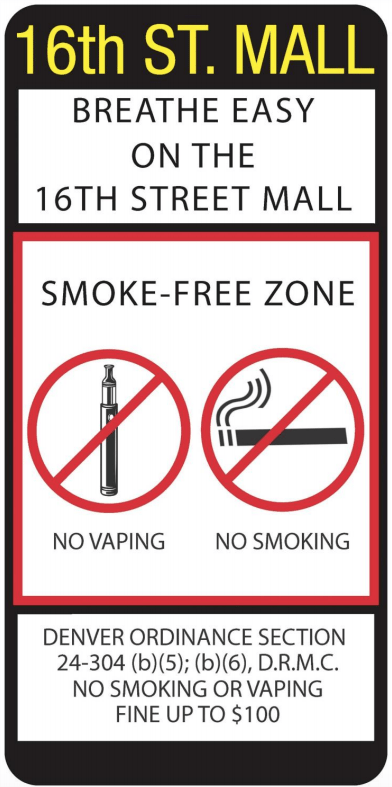

As it's proposed, it would allow police officers to issue tickets up to $100 to anyone smoking or using an e-cigarette on the mall or within 50 feet of either edge.

Failure to pay the tickets would mean that people could be hounded by collections agencies, and their credit could suffer. It would not be possible to be arrested for violating the ban.

Some of the strongest criticism came over homelessness issues.

Diane Thiel, one of the Denver residents who spoke in opposition, described it as "persecution dressed up as a health measure."

Terese Howard, a member of Denver Homeless Out Loud, said that the ban could prove "discriminatory." She pointed to Fort Collins, where 83 percent of the people cited for violating a public smoking ban over a 10-month period were homeless, according to records compiled by DHOL.

Howard later said that her main concern is that police officers will specifically target homeless smokers in order to force them off the mall.

Councilman Rafael Espinoza was sympathetic to that concern, pointing to data that shows smoking is more common among people with lower incomes.

"I am concerned that we are targeting a very, very vulnerable population," he said. He said that a smoking ban seemed like it continued a trend of "privatizing" the mall. "We have ... dumped millions and millions of dollars since the mid-eighties into sterilizing it," he said.

Council members Robin Kniech and Paul Kashmann also asked who the ban would affect.

"I also am concerned with people with no other option, people who can't go home to smoke," Kniech said. Kashmann requested "reasonable options for those who can't go home, can't smoke in their car."

Both Kashmann and Espinoza said they would like the bill better if it were reversible or if it were temporary, meaning it would have to be renewed after a certain time.

Others argued for the ban's benefits.

Brooks said that the bill is not at all targeted at homeless people. He has seen a mix of people smoking on the mall, including many in suits and ties, and it would be easy for people to walk off the mall for a smoke, he said.

"It's really not that far," he said.

And while some asked whether smokers now would flood Skyline Park or 17th Street, Brooks argued that they would disperse evenly through downtown.

Other supporters of the measure included property owners, medical experts and downtown business officials.

"When you're in the public domain, you have to share it," said Jon Buerge, chairman of the downtown business improvement district. He said that a recent lunch on the mall had been "ruined" by secondhand smoke.

Council members Paul López and Debbie Ortega both said that collecting data could help the city ensure the ban is fairly enforced. Brooks has said that the ban would begin with a "soft" period where officers simply tell people to stop smoking. Once it's in full effect, police still would try to take a light touch, he said.

"It's a campaign of awareness," he said.

Don Cohen, the president of the Riverfront Park Association, said that the ban could make the mall more secure by giving police legal justification to contact more people.

"I've learned that an ordinance that prohibits smoking lays the groundwork for proper legal contact with citizens who might have the potential for disruptive or illegal behavior," he said. "This would be a very powerful tool for maintaining safety and security on the mall."

His organization of residents near Commons Park want to see smoking banned in all parks, especially Commons Park, he said. Brooks said that homelessness services providers had objected to the idea of a full parks ban on smoking and vaping.

Other concerns included the fact that restaurant workers and other employees of mall businesses might want to smoke during their breaks. They may be allowed to do so on loading docks or in alleys; the council members requested more information on how the ban would apply in service areas near the mall.

Councilwoman Stacie Gilmore moved to send the proposal to the full council, and López seconded. There were no objections. The council could hear a first reading on Oct. 23 and hold a final vote on Oct. 30.

More information:

The ban would run the length of the mall and also include all public spaces within 50 feet of its edges, including part of Skyline Park. It would not set aside any designated smoking areas within the mall.

Smoking (but not vaporizing) already is banned within 25 feet of building entries in Denver. But since the mall is about 80 feet wide in many places, that leaves plenty of space to smoke.

Brooks has argued that vaporizers are harmful because they “re-normalize” smoking in public and “create the impression that the use of such devices is associated with a healthy lifestyle.” Plus, you can use them to smoke weed sneakily, he pointed out.

Barry Make, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health, said that the ban proposal had his and his employer's "strongest possible support." Federal research has found that secondhand smoke causes tens of thousands of premature deaths each year in the United States. The effects of vaporizers/e-cigarettes aren't as well known, but they can include harmful additives, including their flavoring, Make said.

About 17 percent of local adults smoke, compared to New York City and Seattle’s 10 percent, according to stats compiled by Denver Health. Both of those cities ban smoking in all of their parks, unlike Denver.

In Colorado, numerous other cities have banned smoking in public transit waiting areas and public transit waiting areas, which Denver also hasn't done.