The student population of Denver Public Schools has grown for 13 years straight, but the enrollment boom is coming to an end -- a result of gentrification and a significant drop in the birth rate, according to the latest expert analysis.

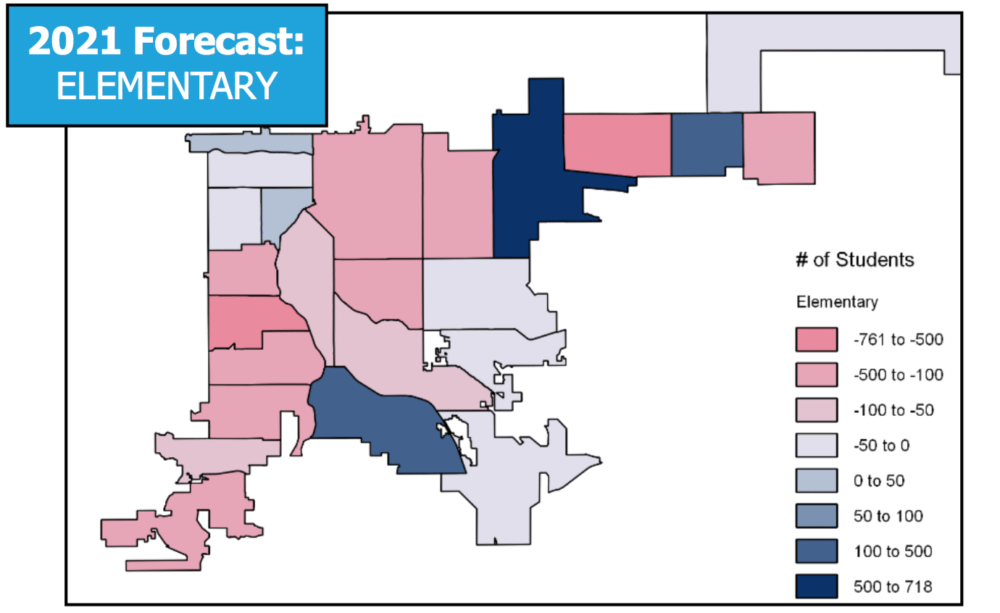

In 2019, the city's student population is expected to fall by about 600 students, enough to fill an elementary school. In fact, kids are disappearing already from the gentrifying neighborhoods where young, childless couples are buying up property.

While enrollment grew slightly this year, it may drop by close to 2 percent between 2018 and 2021. It's a change that already is forcing principals to make painful cuts.

"It has changed quicker than we thought," said Brian Eschbacher, executive director of planning and enrollment services for the schools. "I think it’s a direct result of housing changing faster than it had been in the past."

More people, fewer kids.

"We’ve been in a pattern of building new schools pretty consistently. Some years, we were adding 3,000 students. If you think of an average school, (that's) opening 6 new schools a year," Eschbacher said.

And you might expect that growth to continue. If the roads and ski slopes are more crowded, why aren't the schools?

Well, look at who's moving here. Since 2009, 80 percent of Denver's transplants have been households without children, according to the latest DPS enrollment report.

Now, eventually, you figure that those people might have kids -- but, for many, that won't happen in the thousands of new luxury apartment units that have hosted so much of the population boom.

"While you may have some people in their upper 20s and 30s that may decide to have kids, I don’t think that the kids are going to be living there," Eschbacher said.

An effect of gentrification:

Of course, some of the city's millennial and transplant residents are finding houses. Thousands have moved into neighborhoods like Cole and Elyria-Swansea in search of cheaper housing -- and those places are where student populations are dropping fastest. Again, that's in large part because new families don't have kids.

"This is at the heart of what gentrification and displacement are all about," said Council President Albus Brooks. His kids attend Cole Arts and Science Academy, which may lose 37 students from its rolls next year.

Every kid brings about $5,000 in government funding, so the change could result in the loss of three or more teaching positions, depending on what decisions the school makes, Eschbacher said.

"It could be number of teachers, it could be the wraparound services that they have in terms of nurses and psychologists, paraprofessionals and interventionists," he explained.

The effect is compounded by the fact that families moving into these neighborhoods are less likely to choose neighborhood schools, at least compared to previous residents. In Denver, parents can apply to send their kids to schools across the district.

"I think it is a crisis," Brooks said.

He pointed out that many of the affected schools are low-income and racially diverse. "We're working with Denver Public Schools to figure out how we can start to address some of these issues," he said.

DPS already is trying to prepare schools and neighborhoods for the changes ahead. This is the first time in recent history that the schools have brought in outside consultants to help with its projections, at a cost of about $30,000.

The goal is to "arm schools with information," Eschbacher said.

And the change is not cause for panic. While declines can sometimes result in a downward spiral, with students continually fleeing schools as they lose funding, that doesn't always happen.

"It's happened both ways. We’ve seen schools start to decline individually, and then they kind of refocus and they can go back up in enrollment," he said. In other cases, schools can stabilize at a lower population.

"They shrink down to two classes per grade, and they’re really good at two classes per grade — and that’s like their new level," he said. Bigger, he cautioned, is not always better.

When will it end?

Presumably, even the new buyers start to have kids eventually -- but that may not offset the losses anytime soon.

The school system also is dealing with the fact that people are just generally having fewer children, which has everything to do with student debt, expensive housing and financial pressure.

"When the recession hit in 2009, the birthrate dropped abut 8 percent… Those kids just don’t exist, and it hasn’t gone up in the 8 years since then," Eschbacher said.

That 8 percent drop translated to about 1,000 children per year. As a result, Denver's kindergarten classes are about 10 percent smaller compared to 2013.

"It’s hitting all of them. It was a suburban problem, a rural problem, an urban problem," Eschbacher said.

And that may explain why the districts surrounding Denver are seeing a similar phenomenon.

Aurora Public Schools saw its first recent reduction in enrollment in 2016, when it lost about 400 students, or 1 percent of its enrollment. This year, it dropped 2 percent. It was the first decline since 2007, and the largest percentage decline in 46 years or more, according to enrollment data.

Jefferson County, despite population growth, is losing students too. The district closed a school last year, but the uproar prompted the new superintendent to promise a temporary stop to closures.

"The decline is slow. A couple hundred students, when we had 86,000," said Diana Wilson, chief communications officer for Jeffco Public Schools. "Eventually, something will need to be done."