Wilma and Wellington Webb spent more than a decade working to make Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday a state holiday. During each of their stints as state house representatives, their efforts were stymied by hostile committees who shot down their efforts. Groups of supporters marched on King's birthday to demand its adoption as a holiday.

In 1984, a year after President Ronald Reagan signed the holiday into law at the federal level, Wilma was finally successful, as the bill she'd introduced into the state legislature every year since 1981 was passed by the 54th General Assembly.

When the holiday was adopted, the annual protest became a celebration.

But resistance to recognizing Dr. King's legacy didn't end in the legislature.

In 1992, after the annual Marade had swelled to one of the largest such events in the country, it faced a new challenge: white supremacists applied for the event permit for the usual time and place of the Marade, beating the Maraders to it.

That year, skinheads and Ku Klux Klansmen spewed hate speech as the marchers passed by peacefully. But when the event was over, some angry Maraders circled back to face their detractors. The day ended with rioting in the streets.

"We saw that coming," said Terry Minggia, one of the original Marade organizers.

That's because the year prior, Minggia told Denverite, counter protesters stood atop the old RTD building at Colfax and Broadway performing Nazi salutes. A story from The Rocky Mountain News on January 22 described the group of 35 as "noisy," "mostly teen-age white supremacists."

That incident didn't cause much of a stir. Vern Howard, the current MLK Commission Chairman, told Denverite that emboldened white supremacists to up the ante.

"When they found they couldn't incite a riot," he said, "that's when they would use the State Capitol grounds."

Howard and Minggia said they weren't surprised that the Marade attracted such vitriol. Briggs Gamblin, Wellington Webb's former press secretary during his time as mayor, said that many Denverites were shocked by such blatant racism.

The city had its problems, he said, but after Federico Peña's popular run as mayor followed by Webb's election in a race between two black candidates, "the feeling was that Denver was a pretty tolerant and diverse city."

When the Klan got the permit for the Capitol, Gov. Roy Romer denied their request in an effort to keep them off the steps. The KKK appealed to the American Civil Liberties Union, who agreed to represent them in federal court, winning the case and preserving the Klan's hold on the permit just a week before the Marade.

David Miller, who was the ACLU legal director at the time and worked on the case, told Denverite that the decision came down to First Amendment freedom of expression.

"We were faced with an issue that we believed represented a true constitutional right," he said. "It was a very serious discussion."

He said the case also questioned the very nature of public space. Until 1992, whether or not the Capitol grounds was "public" had never actually been established.

With the Klan legally free to hold their rally, the city braced for conflict. A story in the Rocky said the Denver Police Department cancelled officers' time off, staffed the Capitol with 125 officers and borrowed a helicopter from Jefferson County. State Patrol, who has jurisdiction over the Capitol, had an additional 140 officers on standby.

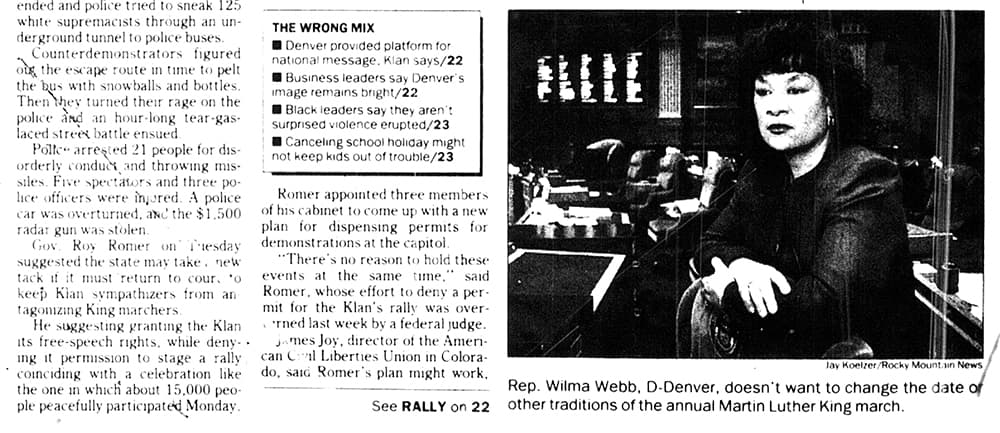

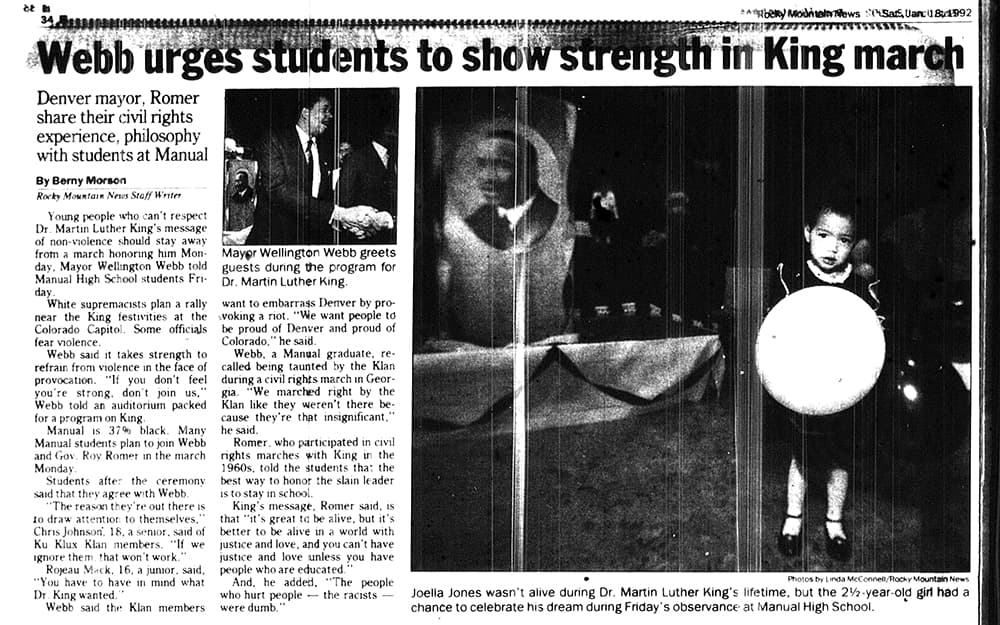

Wellington Webb paid a visit to Manual High School. "Young people who can't respect Dr. Martin Luther King's message of nonviolence should stay away from a march honoring him Monday," the Rocky reported him saying. "Some officials," the story said, "fear violence."

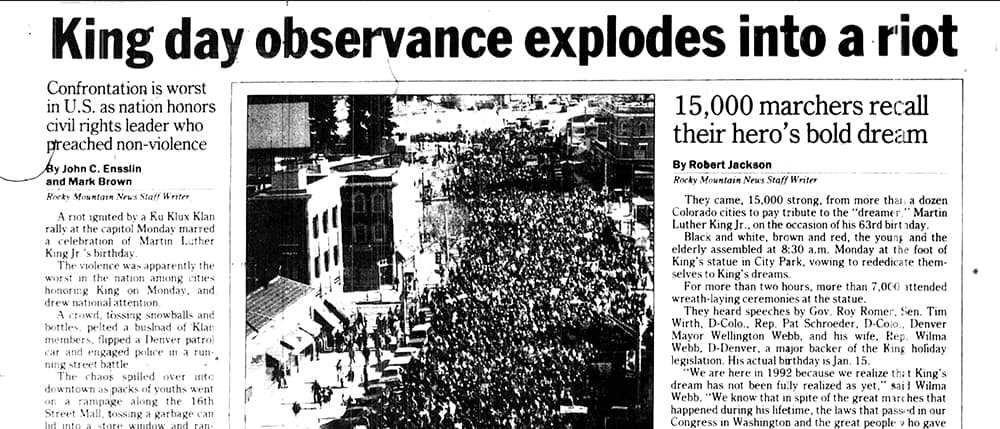

Headline: "King Day observance explodes into a riot"

On Jan. 21, the Rocky Mountain News reported that 15,000 people "joined in a peaceful march" before the white supremacists' provocations gave rise to conflict. Kerry Appel, Kurt Bauer and Stephen Hume were each wielding video cameras and caught much of what happened next.

Their footage, which is edited and on YouTube, first shows the skinheads and Klan members marching down 14th Avenue and yelling "white power" on the Capitol steps. But images of the Marade crowd outside the police line reveals that, though loud, the white supremacists were vastly outnumbered. As the angry crowd grew around them, it became clear that a confrontation was brewing.

"Once the rally was over," said Bauer, who was filming the Klan rally from inside the police line, "it was like: Where do we go?"

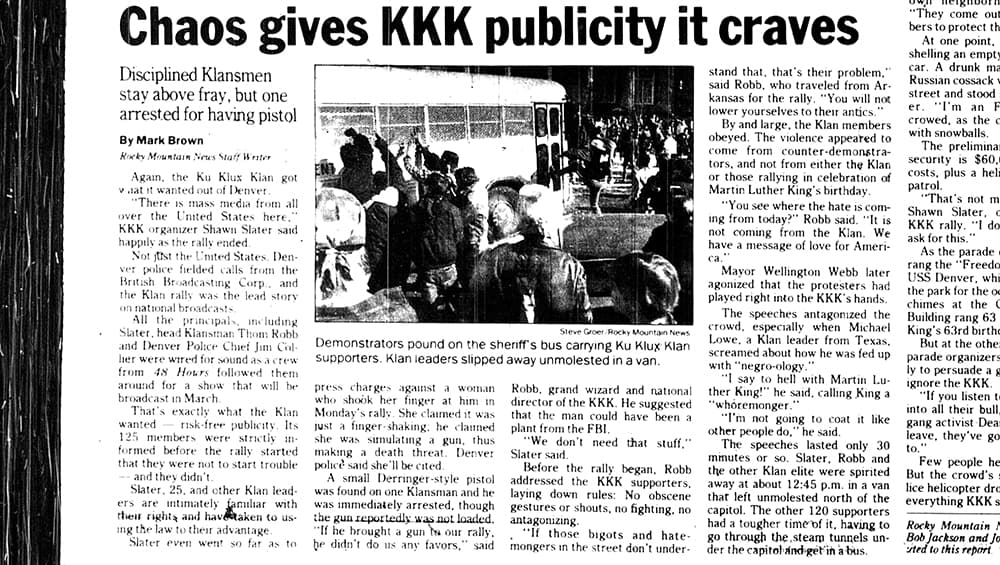

The answer: inside. Bauer's footage shows state troopers escorting skinheads into the Capitol basement and through a service tunnel to an office on Sherman Street. In little time, the angry post-Marade crowd finds them and begins hurling snowballs at the door. Then, police rush the white supremacists across the street, through a barrage of flying snow and glass bottles and into a prison bus to make their escape.

Even though the provocateurs had left the scene, the crowd continued to rage.

Vern Howard, who was just a volunteer then, said he watched the scene unravel from a feed of security cameras inside a city command center. "We saw a crowd of wonderful people marching for unity love and peace," he recalled. "They were in a powder keg that someone threw a spark into, and then they were fighting for survival. That's exactly what it looked like."

"The breaking point for police came at 1:12 p.m.," the Rocky reported. "Chief Jim Collier was urging restraint when he learned that the mob had turned over a police car and was trying to set it ablaze. The time for subtlety and patience had ended. 'If you need gas, use it,' he ordered into a cellular phone."

"That much rage, passion and emotions were so high that the crowd turned on itself," Howard said.

Bauer's footage shows just that. Older marchers yell at angry youths, trying to stop the riots.

"You guys didn't die for anything, he did! This is his day to celebrate, not yours," one older man says. "This is not gonna solve anything!"

To that, young people responded:

"Do you see peace? Have you ever seen peace in this country?"

"We have to stop 500 years of genocide, that's what it's all about."

"It's 1992, why are we still going through this shit?"

After the crowd was dispersed on Capitol Hill, what one report called a "mob" continued down to the 16th Street Mall, smashing a sporting goods store window and looting it.

At the end of the day, the Rocky reported $15,000 in property damage and 21 arrests.

After the conflict, one Colorado lawmaker tried to put the day's events in perspective for the Rocky. From the paper's story the day after the riot:

"Inside the capitol, Rep. Jerry Kopel, D-Denver, talked of irony. Fifty years ago, the Nazis were trying to reach the 'final solution.' And 66 years ago, KKK members weren't assembling on the front porch of the statehouse -- they were inside, as lawmakers, he said. 'The fact that they are outside in Denver today, you cannot say it can never happen here,' Kopel said. 'It did happen here. Here in Colorado.' Lawmakers and staffers clustered around windows in the House chambers, watching anxiously as people assembled outside and waiting for something to happen."

Later that year, the permit battles continued.

In September 1992, the Rocky reported that the Klan had again gotten to the state permit office first. Mayor Webb worked with city attorneys to try to find a legal way to strip them of the space, but he was unsuccessful. Instead, the Marade took a different route and marched on 18th Avenue to avoid confrontation. Wilma Webb called it "the high road."

Once again, there was violence after the march. It was clear that organizers had to get ahead of the problem. After the 1993 Marade, organizers showed up at the state permit office before dawn; Klan members arrived minutes later.

"There was a focus," said Press Secretary Gamblin, who was there that morning. "Let's get this application in, and let's get it stamped."

They beat Klan leader Shawn Slater to the stamp by just two minutes.

The next year, in preparation for the 1995 Marade, organizers and supporters made sure they'd have the permit by camping out in front of the office for days. It was as much symbolic ownership of the space as it was a practical tactic.

"I was down there every night," Wilma Webb told Denverite. The scene, she said, was one of pride. Volunteers sat around, told stories and sang songs. She and others brought hot food and coffee.

There was some fear that they could have been attacked, but the waiting group had a team of Guardian Angels watching over them every night.

"It was not easy," said Colorado Guardian Angels founder Sebastian Metz. "Imagine standing outside for concert tickets in the worst part of the winter for four days."

In the end, the Klan never showed up. "It was the dignity in the way that we did it that made it successful," Wilma Webb said.

It wasn't long after that the state permit office changed their policy to allow groups to keep permits for annual events without waiting in line, meaning the Marade's status at the Capitol wouldn't be challenged again.

"We're always going to have to be strong in terms on promoting love and brotherhood and appreciating the different kinds of people that make up the world." Webb said. "We always need to make sure love is the force that drives us."

The 2018 Marade will begin at Civic Center Park on Monday, Jan. 15th (Martin Luther King Jr. Day). Speeches start at 9:30 a.m., then the march leaves for Civic Center Park and the Capitol at 10:45 a.m.