In November, Denverites narrowly passed an ordinance that requires new, large buildings to include green space on their roofs. We're always interested to explore Denver as an urban ecosystem, so we went asking some local experts: Will green roofs be good for animals?

The answer: It all depends on what you grow. Native animals generally need native plants to thrive. Plant the wrong thing, and you won't be too helpful.

There is indeed a need.

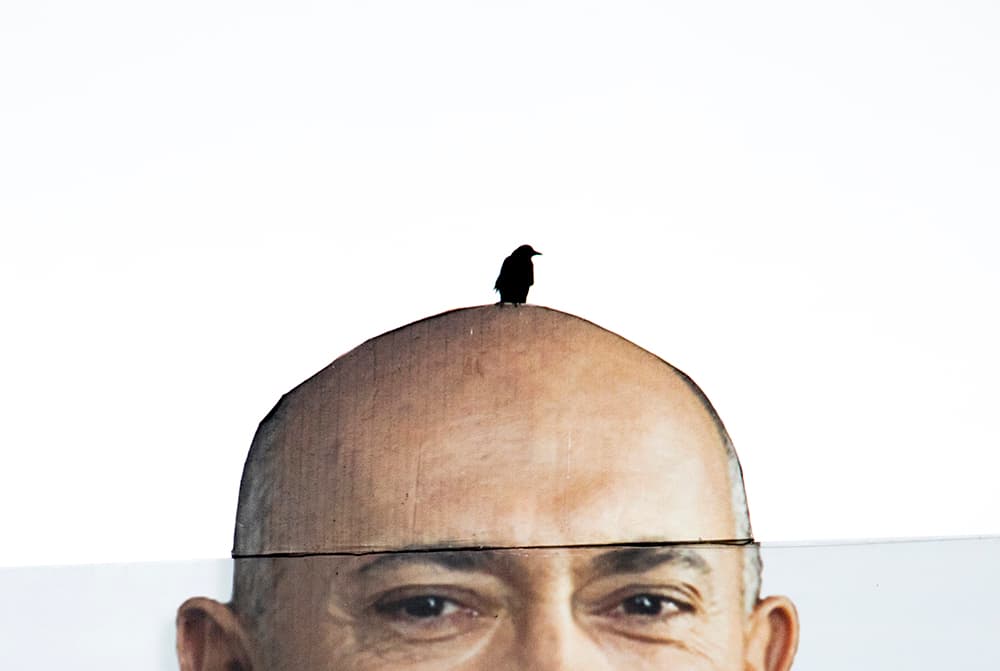

To start, let's narrow this down. There isn't much chance that deer or urban bunnies will make their way onto green roofs, as cool as that would be. But birds and bugs could. As it happens, they're both in need of a little support.

In December we explored how climate change and development have diminished resting places for birds traveling between Mexico and Canada in what is known as America's "central flyway" for migration.

Last spring we followed bee guru Gregg McMahan around during swarm season. While he said longer warm seasons (due to climate change) might actually be good for the metro area's 500-plus bee species, they're going to need more food to make it through the year. As with birds, development has diminished many areas that once fostered bee food.

What's it gonna be?

Green roof advocates are most interested in lowering energy use (to battle the "urban heat island" effect) and mitigating Denver's air pollution problems. The ordinance does not dictate what kinds of plants go on roofs. As far as their primary goals go, any plants should do the trick. But when it comes to helping wildlife, what you plant is crucial.

Particularly, said Denver Museum of Nature and Science (DMNS) Senior Curator of Entomology Dr. Frank-Thorsten Krell, if you want to help native species, you've got to grow native plants.

But this introduces another problem. Denverites prefer green grass and roses -- which are definitely not indigenous.

"If you want a lawn, that's crap. There are no lawns in Colorado. There shouldn't be," Krell said during a Denverite expedition to photograph his beetle collection. "Our grass should be yellow most parts of the year, that's how it is."

Planting what's pretty, but foreign, results in a "very disturbed environment," he said. Manicured neighborhoods don't serve native animals; in fact, he said, they invite invasive species. Krell's been working on a citizen science project to study Japanese beetles, the shiny but pesky eaters of roses who have infested the metro area. Despite a few outlying suburbs, he said, they've basically taken over the city, a result of our penchant for non-native plants.

Dr. Garth Spellman, DMNS's curator of ornithology, echoed a similar outlook for birds.

"If you're just going to plant foreign ornamentals," he said, "it's not gonna be a good place for local birds."

Kristina Williams, an entomologist who trains beekeepers in the Front Range, told Denverite that planting native species is about more than animals' preferences. Plants that are supposed to grow in Colorado can take root without need for insecticides or fungicides. That's a pretty important consideration for animals who may try to take refuge on your roof.

But will these critters actually make it atop your skyscraper?

This is the last piece of the puzzle. According to the experts we consulted, the answer is not yet known. Widespread use of green roofs around the world is in its adolescence. In Denver, it's still untested.

One thought from bird expert Spellman: "I can't imagine they'd want to descend 800 feet every time they want to feed."

Then again, if insects made their way on top of buildings, maybe birds wouldn't have to go too far to eat. But that's untested, too.

"It will be really great to have someone do a study," Williams said.