Phil Watkins slides a glass cutter over a golden-toned piece of stained glass, then snaps it apart with an ease that only comes with a lifetime of experience. The window was recently taken from the Molly Brown House for repairs -- and Watkins believes the piece was first created by his great-grandfather, Clarence Watkins.

He's the fourth to continue his family's stained glass work in Denver, one of the area's oldest enterprises, and he comes from a generations-long line of artisans stretching back to 17th-century England.

The Watkins' historic work can be found all over town, from the Brown Palace Hotel to Fairmount Cemetery. Seeking out the family's multicolored windows across the city is a lesson in architectural history. A flourish for those who could afford it, their stained glass illustrates where wealth lived for a century, from Victorian mansions, to mid-mod bungalows and many buildings in between.

Capitol Hill elite turned silver into stained glass

In the late 1800s, Denverites flush with silver-rush cash began building lavish residences on the hillside recently up for sale by Henry Brown (of hotel fame).

"Stained glass kind of followed," Phil says as he works. When people had extra money and wanted to add something nice to their homes, he says, they often went for fancy windows. In this era, those windows were grand and detailed, often with motifs that added medieval flare to the mansions topped with ramparts and terraces.

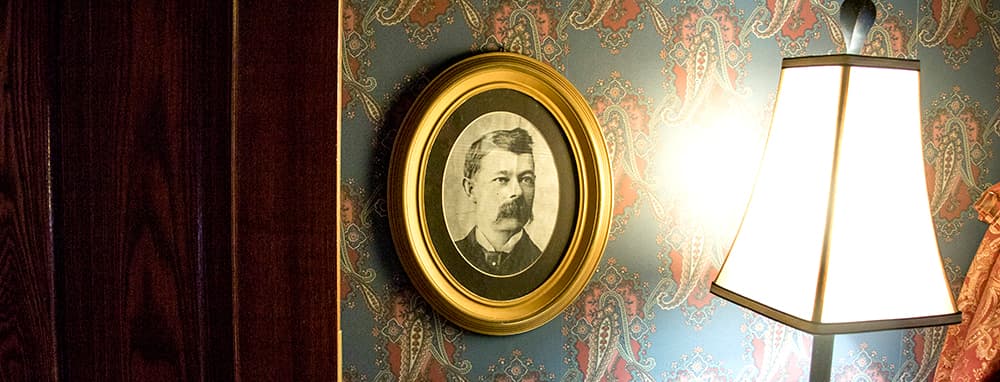

In those days, Clarence Watkins decked out the neighborhood's most desired homes: those designed by William A. Lang. The star architect rose to fame at a time when the city was flowing with cash and becoming metropolitan. Known for his residential work, he designed more than 250 buildings in Denver, which kept Clarence very busy.

Among their collaborations was Castle Marne, now a bed and breakfast, which features a huge glass mosaic of a peacock. Lang also built the Molly Brown House. Even if Phil can't be 100 percent certain who made its decorative window, his shop is now responsible for the window's upkeep.

During a recession, the stained glass business took sanctuary in houses of worship

The Panic of 1893 ended Lang's fortunes. Commercial and residential construction halted, apparently sending the architect into a "downward spiral." Clarence Watkins, on the other hand, still had plenty to work on: Denver's churches.

Annie Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver, says that church construction wasn't necessarily in sync with residential building patterns. The massive projects were often funded by a congregation and in the works for years. Thus, religious construction continued into the new century.

Those churches would come to house some of the Watkins' most cherished work. Their list of religious projects is vast and includes some of Denver's oldest, including the 1910 church on Ogden Street that once housed St. Paul United Methodist's congregation and is now Belong Church.

During Denver's second boom, the windows started moving south

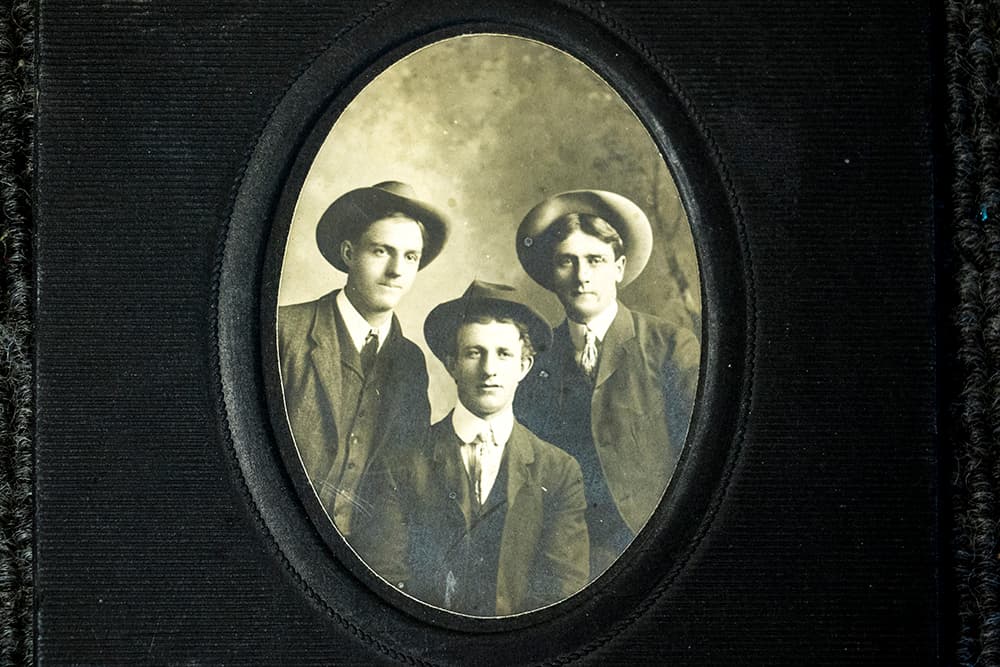

By the time World War I began, Clarence's son Frank had taken up the family business. He spent his youth as an adventurer, an avid fisherman who, Phil says, was "born under a wandering star."

Once, Phil says, Frank hopped a boxcar to San Diego, only to fall asleep, miss his stop, then wake up as the train halted in the middle of the Mexican Revolution. He was shot in the arm while watching the battle from atop the car. Frank also played semi-pro baseball on Merchants Park, Denver's old ballpark that famously hosted Babe Ruth.

The family business stopped altogether during the war, when the government came for their lead to make ammunition. But after the dust settled, Denver saw its second major housing rush and the Watkins were again flush with residential work.

This time around, the windows were a bit smaller and more widely distributed. In the '20s, Phil says, many of the Washington Park bungalows began to spring up on the west side of Downing Street. Many were furnished with decorative glass over the front door or featured smaller, south-facing windows.

Frank was cranking out glass in record quantities. With a staff of 25 workers, winters were spent in the studio stacking glass as high as the ceiling. When construction projects began again in the spring, builders needed only decide which pre-set sizes they wanted and come pick up the readymade windows.

The Great Depression finally slowed the Watkins' work

Almost all development ceased when the Great Depression struck. Jane and Phil say Frank made windows for free just to keep himself busy.

There were some paying jobs to be had. While most of the country languished in poverty, some of the ultra-rich began to build enormous properties. The Phipps Mansion was one such project. Completed in 1933, the 54-room home at 3400 Belcaro Dr. was constructed along with the very exclusive Belcaro neighborhood.

The way Phil and Jane tell it, those sizable projects provided welcome work for artists like Frank. The Phipps Mansion still contains a number of his windows.

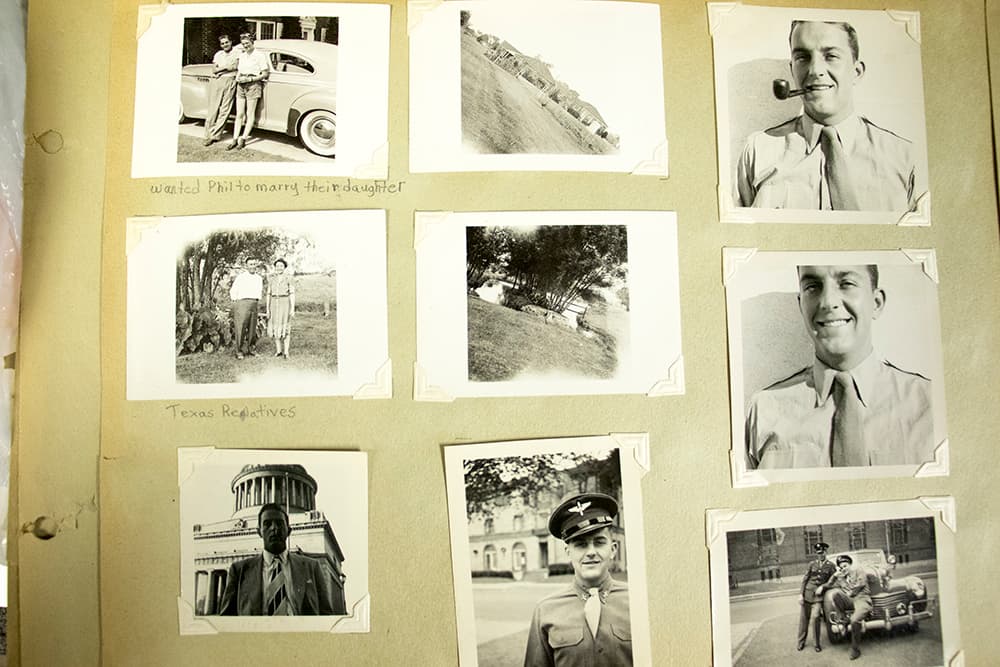

During World War II, Frank was conscripted by the military to make fan belts at the Gates Rubber Company. He hated that job, Phil says, and left without even collecting his last paycheck when the war ended. Another housing boom followed, though a little more slowly this time. Nonetheless, a new crop of neighborhoods once again gave life to the Watkins business.

By then, Phil's father, Phil Sr., had taken the reins. Often working with young Phil Jr. at his side, the family produced many windows for new midcentury-modern neighborhoods cropping up in south Denver.

"Everybody wanted a stained glass window in their house then," Jane says. In this new cycle, the family's work opened up again to a larger audience.

"They were regular people instead of the wealthy people," she continues. A car, a dishwasher and a Watkins window by the front door, she says, "It was kind of the American dream."

There's still new Watkins glass in town — and restoration work

Today, Phil and Jane see themselves as protectors of the family's work. Among the few remaining stained glass experts left in town, Phil and Jane continue to take on new projects -- say, for a synagogue or the Colorado Convention Center -- and windows by Phil Sr., Frank or Clarence Watkins still show up in their office for maintenance.

"Its almost a legacy that you need to especially protect," Jane says, to "give new life to the family's windows for future generations."

"Responsibility," she says, "that's one word for it." At that, Phil agrees with a solemn nod.