Kendra Black swung her red Lexus hybrid around the yawning wide avenues of southeast Denver and unleashed one volley of criticism after another.

There was the "yucky" Walgreens and "that stupid Target," strip malls that were "awful," "shitty" and a "missed opportunity," while an "outrageous" storage facility monopolized valuable real estate next to a light rail station. On Hampden Avenue, she noted, you can go nearly a mile without seeing a crosswalk.

This wasn’t just another armchair critic. Born and raised in District 4, Black is the councilwoman serving this suburban swath of south Denver. Each epithet is another piece of evidence in a case that she’s been building for three years now: The city's outlying communities desperately need a dose of creativity and investment.

She has called for the city to bring its walk- and bike-friendly urban ideals out into the sprawl. Increasingly, it seems that she has the support of both her constituents and the administration.

“We are having a shift in thinking down here," she explained. "We’re not ever going to have a Main Street …. but what can we do to give people a sense of place?”

Depending whom you ask, change here is either happening way too fast or way too slow.

Some of Denver's outlying neighborhoods have become refuges for low-income homeownership. Others have seen gentrification and intensive development, with new apartments cramming in alongside historic houses near light-rail stations.

On the south end, city planners are asking whether they can rescue failing strip malls and undo decades of car-heavy design. In the northeast, they're wondering what to do with the city's last open acres.

Along arterial roads -- the Hampden Avenues and Colorado Boulevards of Denver -- traffic's getting worse and more people are arriving by the day. All throughout, people are asking: What happens when urbanist ideas leave the city core? What does it mean to live outside of Denver's downtown spotlight?

(We're going to be talking about these issues and these areas a lot in the near future — sign up for our newsletter to stay in the loop.)

"There’s some desire to be recognized as being more closely related to the rest of the city. You hear comments, 'We’re part of Denver, too,'" said city planner Courtland Hyser.

The calls for change are growing.

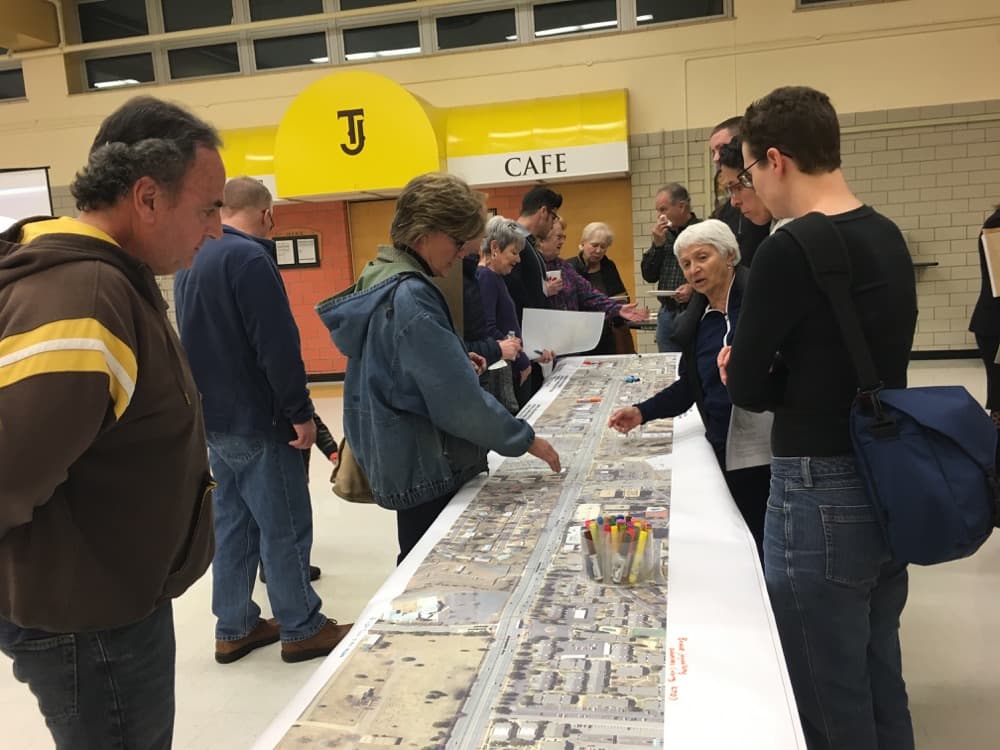

Nearly 200 people crowded the cafeteria of Thomas Jefferson High School on a recent weekday evening -- far more than I expected to find at the first stage of a road-planning exercise.

Councilwoman Black stood before their rows of folding chairs and laid out an “aspirational” idea: “We’re a very car-centered part of the city,” she said. “People want to walk places, ride their bike places, and that’s very difficult in southeast Denver.”

The event marked a new push to remake Hampden Avenue. Corridors like this -- the arterials -- are everything that's wrong with outer Denver, at least from an urbanist's point of view.

At the meeting, city staff laid out long, scroll-like maps of five miles of the avenue. They showed a half-mile stretch with no sidewalks, mile-long deserts without crosswalks. The corridor also is home to the new Target that, with its sprawling parking lot and unremarkable design, spurred Black to run for council.

So, for an hour, visitor scrawled suggestions in red ink: “need sidewalks,” plus requests for traffic calming devices, multi-use paths and channelized turns — some of the strategies you might find in the transit advocate’s playbook.

This push, in part, is coming from a wave of new residents and homeowners.

"You have neighborhoods where a large younger population is moving in, and they want to move to less car dependence. They don’t want to only be driving around," said Carrie Makarewicz, assistant professor of urban and regional planning at CU Denver.

But Black's also tapping some long-running frustrations. Walking the room, I found young parents and retirees alike who wanted to see their stretch of Denver reformed.

“This is the least pedestrian-friendly part of the city,” said John Weeda, a resident of University Hills since 1987.

Zephrine Hanson said her new home in Hampden Heights was perfect — well, almost. “It’s not going to sound believable, but everything I ever wanted ended up in that community,” she said. The Air Force veteran walks with her three kids around the “grandparentish” neighborhood, but she won’t take them farther.

“There’s no way we can walk Hampden with our kids,” she said.

Jody Davison, with her 1.5-year-old toddling behind her at the meeting, said that her family bought into University Hills a few years ago in search of the “most bang for our buck.” Incredibly, they moved to the neighborhood on Denver's southern edge without a car. Even so, she wasn’t exactly optimistic about the chances of an urbanist makeover.

“There’s a lot of work to be done,” she said. “It would be a miracle if it were walkable.”

Most of south Denver wasn’t built for walking.

It wasn’t built for cute co-working spaces, strolls to dinner, or pretty much anything other than peaceful backyard living.

It’s largely a product of the post-war housing boom, when the avenues radiating through the city seemed to offer unlimited space and opportunity. The main roadways -- like Hampden and Colorado -- filled up with shops and businesses. Traffic, we presume, was not always a nightmare.

Now, that vision is fraying at the edges.

"We’re already gone from the days of peak traffic hours. It’s pretty much a plateau from 8 to 5," Makarewicz said.

Models from DRCOG suggest that the typical metro commuter's time in traffic could increase by nearly 60 percent by 2040. That will be driven in part by the recent construction of apartment buildings along the arterials, plus growth in the outer suburbs, according to Makarewicz.

"If you add housing density and job density without adding greater mobility options, you get congestion. Density alone does not lead to transit," she said. In other words, more people are living along the main roads that serve the outskirts of the city, she said -- but they still need their cars to get around.

"If you have those broken sidewalks, missing crosswalks, people are forced into their cars. You can’t have density without mobility," she continued.

Increasingly, city officials support change in south Denver.

To Councilman Kevin Flynn, of southwest Denver, it all comes down to transportation. “What we need are some basic investments in mobility first,” he said. “There’s kernels of opportunity there.”

Councilman Jolon Clark, too, thinks the city is at a critical point. "We can’t continue to grow at the pace that we’re growing and continue to be a western, single-occupancy, vehicle-dominated city,” he said.

And the city administration by all appearances is on board with this new philosophy.

"We can’t continue to grow and move single-occupancy vehicles the way people would like us to," said Crissy Fanganello, director of transportation and mobility for the city. "It doesn’t work. There isn’t the space available."

That shift comes with some tradeoffs, she acknowledged — including an end to the car-first ideas that bulged Hampden Avenue out to eight and nine lanes in the first place.

“We are not looking to widen our streets, for the most part,” Fanganello said.

It’s simply too costly to keep building out roads as a solution, she said, citing the $30 million it took to widen a single mile of Federal Boulevard. Transit advocates, meanwhile, have long argued that bigger roads simply entice more people to drive.

This shift has the potential to make for longer automobile commutes, Fanganello acknowledged. “The response from the community was ‘OK.’ They were good with that,” she said.

Well, not quite everybody. More on that later.

What's holding them back?

While the desire might be there, the money’s just starting to arrive. Consider the city’s recent $1 billion bonds package, only a small fraction of which is going to southern and eastern Denver.

A few million bucks went to districts like south-central Denver, compared to $100-million plus in funds for some of the central and northern areas.

That’s to be expected. The city is focusing on densely populated redevelopment zones, like the $55 million it set for Colfax Avenue’s bus-rapid transit projects.

“As you know, we’re not getting a whole lot out of it. On the other hand, we’re a newer part of town,” as Flynn told a neighborhood meeting last year.

But it also might be a function of political will. Colfax boosters successfully campaigned for the city to pitch in another $20 million from the bonds for additional improvements. Throughout the central city, organizers are forming miniature governments that can command serious budgets and kickstart major infrastructure projects.

The outlying neighborhoods aren’t nearly as organized. They’re still working with neighborhood associations and volunteer groups. They don't have large budgets, and they don’t have full-time staff, so they tend to play a more reactionary role.

That’s changing, though. In one part of southwest Denver, neighborhood organizers are so frustrated with broken sidewalks and lacking amenities that they might also form districts. And, for her part, Black wants the city to think about a sea change.

“The city’s been instrumental in reshaping downtown, but they don’t need to do that anymore,” she said. Her stretch of Denver, she said, should be an "urban renewal district."

What's happening now?

There have been signs of change already.

In the past, "we have prioritized moving traffic as quickly and efficiently as possible. Sometimes that resulted in less-wonderful land use or feeling for a neighborhood," Fanganello said.

"We’re kind of shifting back the other direction. 'I want my neighborhood to have a certain feel to it. I want my streets to be comfortable.'"

Most obviously, there's light rail: It's been more than 10 years since RTD expanded its rail lines to the south in the T-REX project. Denser, urban hubs have started to spring up around some of those stations -- though others haven't changed much.

The new "multi-modal" philosophy is also appearing, slowly, as the city rebuilds roads and other infrastructure in the area. Hampden Avenue, for example, scored $5 million for pedestrian improvements from the bonds, which could happen as soon as 2019.

Another $3.7 million will pay for a new underpass for cyclists and pedestrians in the High Line Canal Trail under Yale Avenue, also in Black's district.

Farther north, a new pedestrian bridge will connect Evans Station to neighborhoods across the rail corridor at a cost of about $13 million. On Federal Boulevard, the city is considering "bus only" lanes for rush hour, plus pedestrian improvements.

And the recent bonds also set aside about $31 million to build sidewalks around the city, which could help fill that half-mile gap on Hampden.

But Makarewicz worries that Denver doesn't yet have the transit muscle to change how people travel.

"We have a struggle with our transit agency (RTD) in this region. It doesn’t have the money and capacity to keep up," she said, referring to its sprawling service area and its driver shortage.

The city may respond by taking transportation questions into its own hands, creating a Denver transit agency. It also is piloting wireless technology that could improve pedestrian crossings.

What does the future hold?

This isn't just a transportation question. In parts of Denver, the old pattern of strip malls and offices is sputtering. Retail businesses are facing a dramatic shift, and older offices are bleeding business.

"It’s changed to the point where you don’t have major anchor retailers and centralized retail spaces," said Johnny Marshall, the new owner of Java on the Creek in southwest Denver. Target left and Walmart gave up on its neighborhood market, though King Soopers survives.

It's "like inner-ring decay," Flynn said. There are bright spots, the councilman noted -- such as the popular new gym that replaced a Safeway grocery store on Jewell Avenue.

Yet Black complains that developers in her district are happily following the same car-oriented patterns as always. “We got a worse strip mall than we had,” she said emphatically during our tour.

And the result, according to Marshall, is that many people are driving even more now. "For the bigger stuff, we have to travel out of the neighborhood," he said.

What will break that pattern? Makarewicz, the professor, said that the influx of residential units could change suburbia. Done right, new apartments and condos can support walkable "nodes" of restaurants, retail and jobs that are easier to serve with transit.

Marshall sees both potential and worries in the new apartment buildings that he's spotted near his shop.

"The more influx of consumers, it will definitely drive sales — but then, it’s going to increase traffic on our roadways and within the consumer spaces," he said.

These questions could soon be more formally incorporated in the city's plans. The idea of redeveloping Denver's corridors will be part of the upcoming Blueprint Denver recommendations, according to planning spokeswoman Andrea Burns.

And Ken Schroeppel, assistant planning professor at CU Denver, expects that the city's upcoming planning efforts will embrace higher density and more-frequent transit along its busiest roads.

As that happens, we'll get a sense of voters' reactions.

Jay Welton, a Southmoor resident of 15 years, counts himself a skeptic. He knows traffic's getting worse, and he likes Councilwoman Black's spunk, but he was skeptical about the ideas he heard at the Hampden meeting.

"I didn’t move out here to ride public transportation," he said. “They say, ‘We want more mobility, to walk, to ride bicycles.’ I don’t see people riding bikes or walking. In 20 years, most of them are going to be gone. Are these the right decisions?"

Clare Harris, a resident of College View, is worried by the density that the Loretto Heights development could bring to nearby Federal Boulevard. "It's not a walking neighborhood," she said. "There’s no such philosophy here. The philosophy here is getting by, getting to work, getting your family."

And even some who like the idea of a walkable south Denver find themselves a little conflicted.

“I’m kind of torn. I want it to move swiftly when I’m in the car," said Weeda, the University Hills resident. "But when I’m a pedestrian, I want it to slow down."

This is the first part of a longer series on Denver beyond downtown. To follow along, sign up for our newsletter. And, please, email me if you have any suggestions for the rest of the series.