When you write in with a question, no matter how obscure or relevant, we do our best to answer in the fullest.

A few weeks ago, reader Steven Grupe wanted to know: "Why have American elm trees survived in Denver even as they were decimated in many parts of the U.S. by Dutch elm disease?"

Sadly, Steven, we were not spared.

Quoted in a May 10, 1971, article in the Rocky Mountain News, Denver City Forester George Stadler said the city was once home to an estimated 200,000 elms. That's of 335,000 total trees in Denver, easily the lion's share of shade in the city.

Today we still have a lot of elms, but they're new, mostly of foreign varieties that are resistant to the disease. The American elm, the indigenous species, was killed off in huge numbers between the late '60s and early '80s. Today, there's only 3,810 American elms left according to Denver's tree inventory.

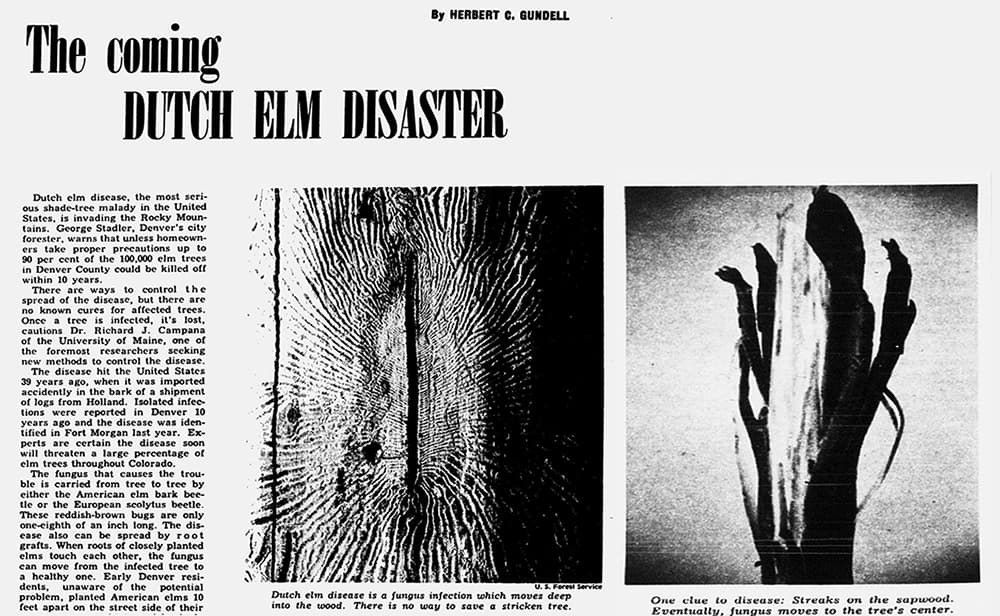

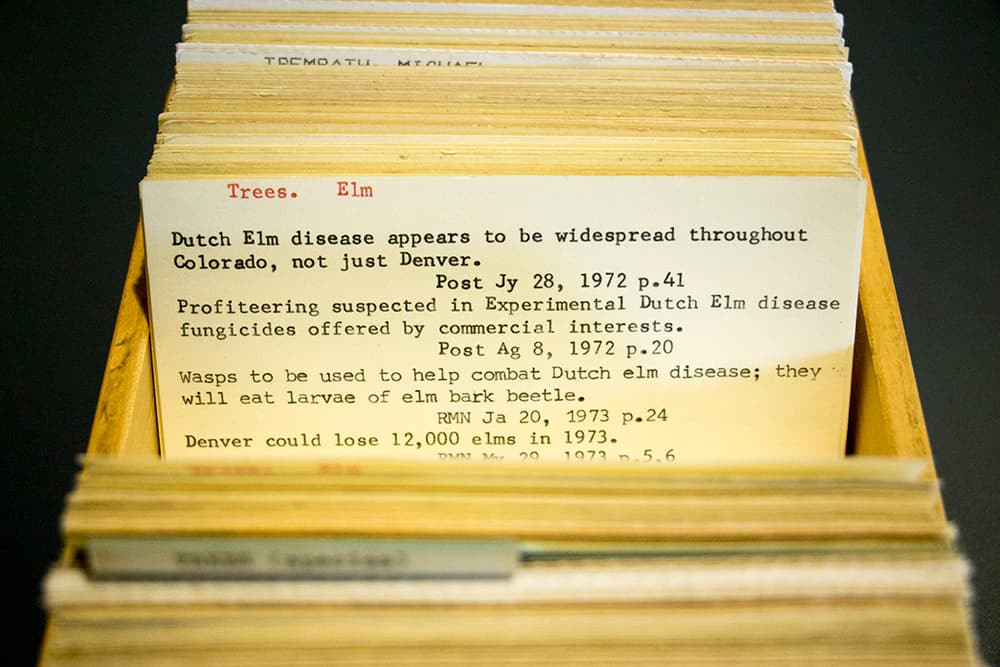

The disease, a fungal infection spread by beetles, was a scourge that led Denver media to report on the issue over and over again. Denver Public Library's Western History Collection has no less than 56 entries in its card catalog dedicated to disease coverage.

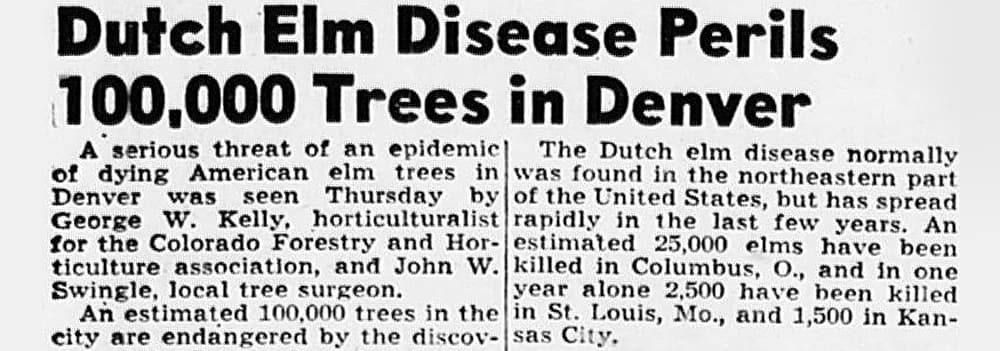

It was reported on as early as 1948. "Dutch Elm Disease Perils 100,000 trees in Denver," reads the headline of one article in the Denver Post that year. "No means of preventing elms from being infected...is known," it said. "Horticulturalists are concerned because a great many of the elms found in Denver have been imported from Kansas City where the disease has made rapid progress."

By 1969, American elms were in full decline and news articles struggled to quantify how many of our trees would fall victim. In August that year, the Rocky Mountain News estimated 70 percent could be affected; a month later, their guess was upped to 85 percent. The Denver Post's guess came in at a whopping 90 percent.

"The loss of much valuable shade and beauty is possible in a few short years if nothing is done," said a Rocky Mountain News article from August 28, 1969. In the tree hysteria, it said, hucksters selling snake oil remedies might start to come out of the woodwork.

"Tree wizards and 'doctors' will soon be making the rounds selling special cures," it reas, warning "residents not to fall for magnetic nails hammered into sick trees or other fraudulent 'cures.'"

The disease's takeover was swift. According to Denver Parks and Recreation data, there were 50 infected trees in 1969. The next year it was 100, then 3,000, then 6,000. By 1972, the city's infected elms numbered 12,000.

But ten years later, American elm deaths had declined. In 1984, the Rocky reported, "The battle against Dutch elm disease in Colorado has nearly been won."

That victory had a huge caveat.

According to Sarada Krishnan, director of horticulture at the Denver Botanic Gardens, it wasn't that society had conquered the infection, there just weren't any trees left for it to kill.

"There are very few patches of American elms left," she said. Nobody even bothers to plant them anymore.

That 1984 story in the Rocky estimated only 30 percent of Denver's American elms remained after 15 years of Dutch elm onslaught. Today, if Stadler's 1971 count was correct, Denver has less than 2 percent remaining.

We do have a little over 10,000 Siberian elms in Denver, the city's fifth-most populous species. But that's not great for future American elm cultivation. Those trees aren't susceptible to Dutch elm disease, Krishnan said, but act as carriers and could still harbor it. Science, she said, still hasn't come up with a cure.

Have a question you want us to dig into? Submit it here!