Since 2002, city-wide plans have divided Denver into "areas of change" and "areas of stability," implicitly promising that most of the city could stay comfortably unchanged.

That philosophy is coming to an end as Denver updates its long-range plans. Draft documents outline a vision in which every neighborhood is constantly evolving in one of four different ways.

It's a substantial shift in the city's mindset, and it's the subject of a series of public meetings that begin this week.

"The point is that change doesn’t necessarily mean private development. Change can mean a lot of different things," said planning spokeswoman Andrea Burns. "We’re looking at ways to suss out the kind of change that a neighborhood needs in all different ways — not just whether it promotes or inhibits development."

What they said in 2002:

The city created Blueprint Denver, a sweeping plan for development and transportation, more than 15 years ago.

In some ways, it correctly predicted the future. It said that streets should be built for bikes and walking, too, and it encouraged mixed-use urban developement.

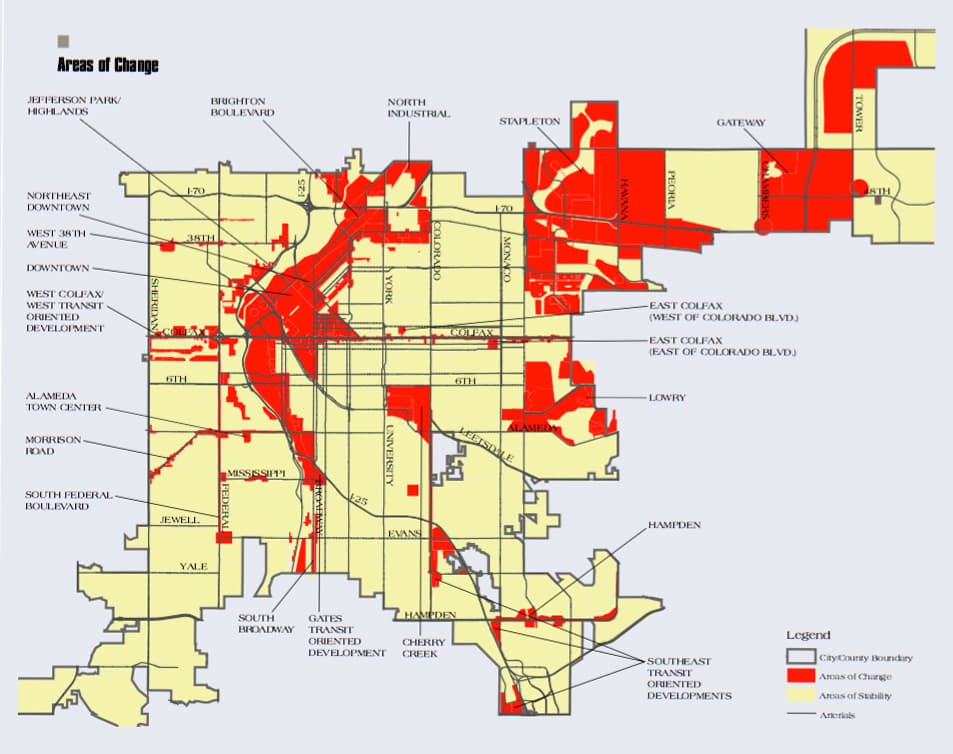

Blueprint also made some guesses about the city's "areas of change" and "areas of stability." It accurately showed the redevelopment of places like Brighton Boulevard, where new apartments abound, and Jefferson Park, where a wave of "slot homes" has crashed into residential neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the plan declared that the city would intentionally limit development in the "areas of stability."

Covering 82 percent of Denver, these areas were supposedly going to see "minimal" change over the next 20 years. In fact, a "central goal" of the old plan was to reduce the number of housing units built across the stable areas.

This helped to entrench the longstanding idea that city centers can redevelop, but outlying residential areas will mostly stay the same.

"The community began to think of the words 'stability' and 'change' almost in a Biblical sense. 'It’s this way and no other way. It is immovable,'" said Councilwoman Mary Beth Susman.

The overall vision was "quiet neighborhoods, vibrant corridors and active districts."

That all came true, to an extent: The areas of change have received 10 times more housing units per acre than the areas of stability. Since 2002, about 67 percent of housing growth has happened in just 18 percent of the city.

Today, the picture's different.

Denver's planners knew that growth was coming, but they underestimated the wave.

Currently, the city's running one-third over the 2002 estimates of housing growth. We've also seen some interesting signs of change in "stable" areas.

In southwest Denver, they're struggling with "decay" as retailers abandon malls, according to Councilman Kevin Flynn. In southeast Denver, Councilwoman Kendra Black says that new residents are calling for walkability and better transportation.

"I think, in particular, we have observed the tension in areas where an area of change butts up against an area of stability," Burns said.

And, on the national level, planning thinkers are asking whether cities should ease development restrictions in the "suburban interior."

Denver is taking on a major planning revamp.

As part of its "Denveright" planning process, the city is updating the Blueprint plan. In a recent press release, the planning department declared that it was time to "move beyond" the change-and-stability model.

So, it seems that the city will try to dispel the idea that neighborhoods can truly be protected from change. Instead, they're emphasizing the idea of making neighborhoods "complete."

The city likely will still direct the heaviest growth to urban centers and transportation corridors, but the rest of Denver "would evolve in smaller ways," according to city documents.

The current plan would introduce four verbs to describe the type of change expected or planned for an area. Neigbhorhoods could be assigned a mix of these qualities:

- Transform - for a place that's expected to undergo major redevelopment.

- Connect - for a place that needs better "access to opportunity," aka transit and jobs.

- Integrate - for a place whose residents are vulnerable to gentrification and displacement.

- Enrich - This one used to be "diversify," according to Burns. It likely describes single-family residential areas, the ones that used to be "areas of stability."

Over the next few months, planners will apply these words across broad swaths of the city. Then, they could be mapped more specifically through the area plans that will be produced across the city over the next 10 years.

On their own, the words won't really do anything.

But they set the stage for changes in how the city approaches each neighborhood.

For example, in an "enrich" single-family area, the city could encourage the creation of new types of housing for people with lower incomes. Possibilities include "appropriately scaled multi-family buildings," and accessory dwelling units, such as "granny flats."

Councilwoman Susman hopes that the new push could help to replace some of the old corner stores that used to stand alongside homes in her east Denver district.

"In the ‘50s, when they decided that we had to have these separate zones — homes here, businesses there -- we lost sight of what makes a livable community," she said.

Councilman Rafael Espinoza is skeptical of just how much Denver can transform itself. There is a "finite amount of resources" for building transit and other infrastructure, he said.

Still, he sees some good ideas in the new planning process. He said that this more “granular” approach could “reinforce the best parts of our communities and encourage redevelopment.”

Go to a meeting:

Denver will hold a series of meetings about the Denveright process. At each one, people will hear more information and tell city staffers their thoughts. Use this map to determine your district, then check the schedule:

- Council District 4: Feb. 20, 5:30 - 7:30 p.m., Thomas Jefferson High School, 3950 S. Holly St., Denver (This will be focused on Southmoor)

- District 9: Feb. 21, 5:30 - 7 p.m., Laradon, 5100 Lincoln St., Denver

- District 1: Feb. 22, 6:30 - 8:30 p.m., Potenza Lodge Hall, 1900 W. 38th Ave., Denver

- District 6: Feb. 22, 6 - 8 p.m., District 3 Police Station, 1625 S. University Blvd.

- District 3: Feb. 27, 5:30 - 8 p.m., Corky Gonzales Library, 1498 Irving St.

- District 2: Mar. 1, 6 - 8 p.m., All Saints Parish Hall, 2559 S. Federal Blvd., Denver

- District 10: Mar. 6, 5:30 - 7:30, Community of Christ Church, 480 N. Marion St.

- District 11: Mar. 7, 6 - 7:30 p.m., Evie Garrett Dennis Campus, 4800 Telluride St.

- District 7: Mar. 8, 6 - 8 p.m., Valverde Elementary, 2030 W. Alameda Ave. (This one will be conducted in Spanish.)

- District 7: Mar. 14, 6 - 8 p.m., DSST Byers School, 150 S. Pearl St. (No Spanish interpretation.)

- District 8: Mar. 15, 5:30 - 7 p.m., DSST Stapleton High School, 2000 Valentia St.

Food, childcare and Spanish interpretation will be provided, except if otherwise noted.

A sign language interpreter or CART services will be provided upon request. Contact [email protected] three business days before the meeting. For other public accommodation requests/concerns related to a disability, contact [email protected].