Affordable housing projects in Denver are not always actually affordable for everyone struggling with home costs in the city.

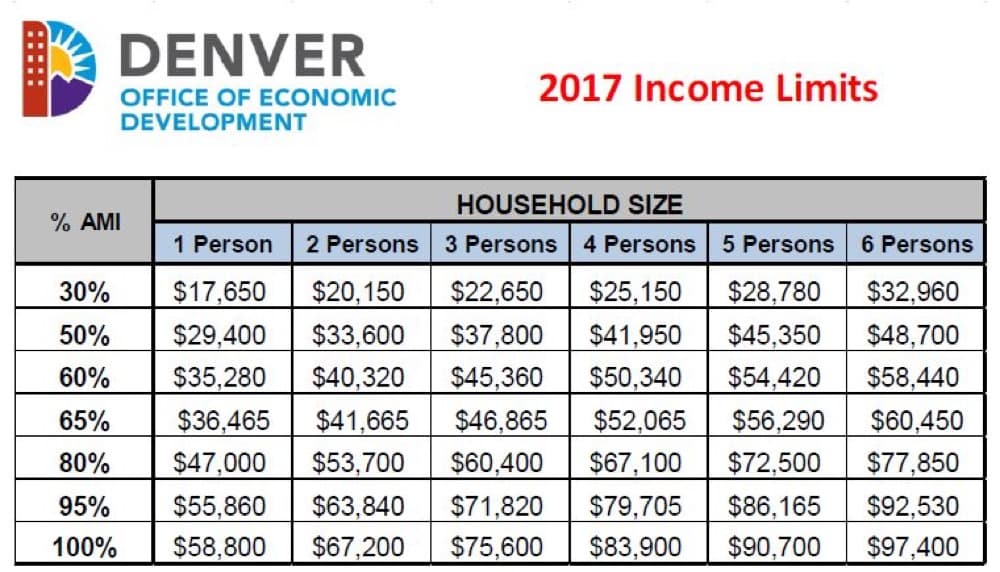

Most of the projects dubbed "affordable" underway in the city are actually being targeted toward residents who make about 60 percent of the area median income — $32,580 for a single-person household or $45,360 for a family of three.

Developers are worried about what's being called "the missing middle" — residents who are making 61 percent to 120 percent of the area median income. And of course, on the other side, there are concerns about a lack of housing solutions for the most cash-strapped members of our community.

What is affordable?

Housing costs are considered "affordable" if residents' monthly rents or mortgages, plus utilities, add up to no more than a third of their gross household earnings.

The rent cap for a single person making 60 percent of the AMI is $945 for a one bedroom. At the same percent of AMI, a three-person family's rent would be limited to $1,309 for a three-bedroom, according to the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority.

What's being built?

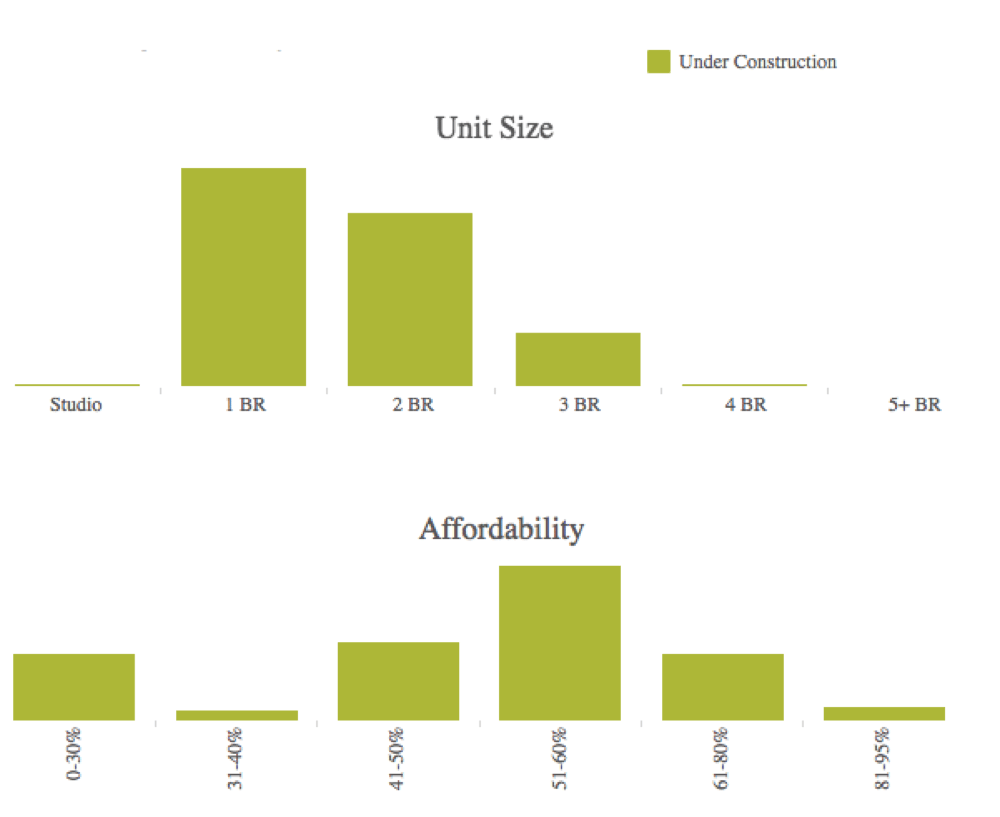

As of Dec. 31, there were 1,075 affordable units being built. The largest percentage — 38 percent or 416 units — of those units were geared toward those making between 51 percent and 60 percent of the AMI, according to city data.

So why build units for those making 60 percent AMI?

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program is probably the largest factor for why developers are building units for those making 60 percent of the area median income.

In a nutshell, Colorado Housing and Finance Authority awards tax credits to affordable development projects. Then developers turn around and sell those credits — often through tax credit syndicators acting as brokers — to investors who want to use them to cut down what they owe in taxes. The program is a huge deal for developers because credits could bring hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding.

But to be eligible for credits a project must meet one of two minimum thresholds: either a minimum of 20 percent of the project units must be rent-restricted for tenants with incomes of 50 percent or less of the AMI; or a minimum of 40 percent of the units must be rent restricted for tenants with incomes of 60 percent or less of the AMI.

Developers mostly build 60 percent AMI projects because that brings in the most rent to cover loans and other expenses of building, said Joe DelZotto, president of the Denver-based real estate firm Delwest Capital LLC.

"There's no big motivation to bring a lot of units below 60 percent because they're really hard to finance," DelZotto said. "We underwrite the rents as the highest possible amount so we can have enough income to cover the debt that's going to come with the project. And every dollar we lose in that we end up with a funding gap."

Is affordable housing charity?

Figuring out development deals involving mortgages, tax credits, grants and soft funding sources like loans from government agencies can be complicated. Pulling together a deal can take more than a year or two, slowing down the process for affordable units to be built, DelZotto said.

"It’s the most complicated puzzle you can put together because you are making a decision to go forward and spend a tremendous amount of money on your pre-development costs and you have so many elements you don't control, like the tax credit rates, where interest rates are going, where the construction rates are going and how much soft funding you're truly going to get," he said.

And while the work DelZotto and other are doing is hard and intended to benefit the community, it's not charity.

"I'm blown away that I make a really good living doing this, being able to provide the housing, which is really cool, but also to create projects that have a broader impact on the community," said Troy Gladwell, a partner with the Denver-based real estate firm Medici Consulting Group.

Gladwell and others can receive a developer fee through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program for putting an affordable housing project together. There's also perceived to be less risk that the completed apartments, condos and houses will sit vacant once they're complete because of the demand for affordable housing.

"It’s hard to make a living in just doing affordable housing for yourself," Gladwell said. "The financing is such that you get a project every two or three years and you end up making $600,000 or $700,000. And when you have salaries, an office, insurance, lights, heating and other overhead, that money just doesn’t go that far."

To supplement its affordable housing development, Medici Consulting Group works on other projects with nonprofits and housing authority clients. Other firms like Delwest Capital might choose to do a mix of affordable and market-rate building.

What about the rest of us?

"The folks that use tax credit housing are working individuals and families that are making $9 or $10 an hour and can't afford to live anywhere else," said Kimball Crangle, the Colorado market president for Wisconsin-based Gorman & Co.

"If we look at the housing plan and the recent housing need assessments that have been done in the city, we see a tremendous gap in housing supply for the lowest AMI thresholds," Crangle said.

People making 30 percent or less of the area median income are the most severely cost-burdened households in the city, according to the recently released Housing an Inclusive Denver report.

In 2016, the City Council approved Denver’s first-ever dedicated housing fund of $150 million to support affordable housing creation, preservation and programs over a 10-year period. The newly adopted plan states that 40 to 50 percent of the city's housing resources will be invested to serve people earning below the 30 percent AMI threshold as well as those experiencing homelessness who need help with rent.

On the other end of the spectrum, 20 to 30 percent of housing resources will go toward serving those who earn 31 percent to 80 percent of the AMI. And an equal amount will be invested for those seeking to become or remain homeowners.

So far, the Office of Economic Development Loan Committee recommended providing $34.3 million to help fund 12 affordable projects — 1,481 rental units. Of that, $58,000 was provided to a one-unit project that restricted rent for those earning above 60 percent of the AMI.

The committee recommended loaning $2.4 million to three for-sale projects — 48 units. Of those, two projects with 16 units would be available to those earning above 60 percent of the AMI.

City Council approval is required on all finance contracts over $500,000. The majority of the projects that went before the Office of Economic Development Loan Committee still need to be submitted for City Council approval.

"If Denver wants to be a sustainable city it needs to value the households that make the city work and that's a diverse kind of household. We need to put value on workers, children, seniors and service those individuals experiencing homelessness" Crangle said. "It's such a big need and the growth that's happened recently has just emphasized the gap we have in housing supply across the spectrum."

Want more Denver news? Subscribe to Denverite’s newsletter here bit.ly/DailyDenverite.

Business & data reporter Adrian D. Garcia can be reached via email at [email protected] or twitter.com/adriandgarcia.