Mike Sickinger has to choose his destination wisely when he hits the town. The self-proclaimed energy geek always makes the trip from his Centennial home in his all-electric Nissan Leaf, and the presence of a charging station at the end of the road usually dictates his destination.

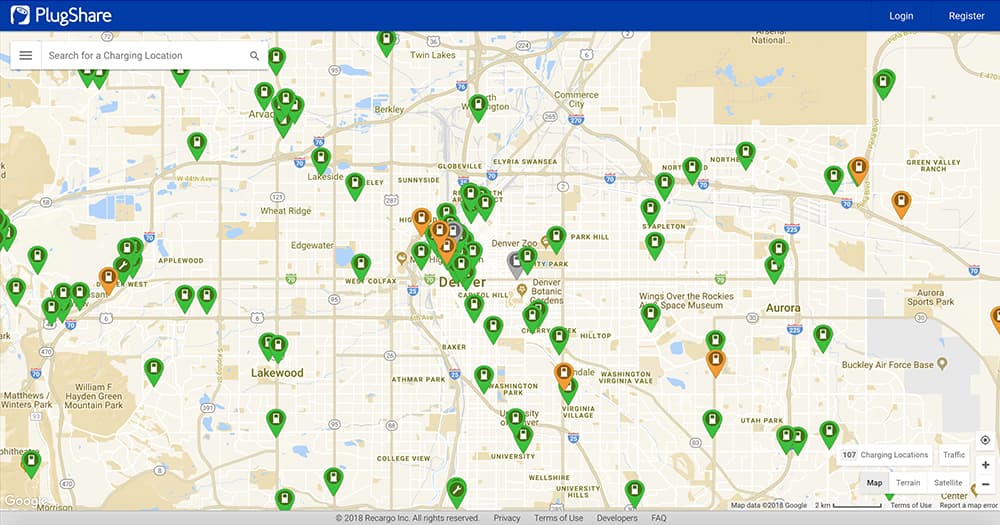

These days, when he heads out for a beer, Sickinger says he's more likely to drive toward Union Station or Lowry than a watering hole along Colfax. While the city reports that there are more than 140 public charging stations in parking lots across Denver, they aren't yet evenly distributed across town.

City officials have been looking toward electric vehicles (EV) to help achieve a number of their 2020 Sustainability Goals and have begun encouraging EV use by installing stations. While EV enthusiasts are thus far pleased with Denver's progress, some say it's going to take a focused effort to bring the juice to some of Denver's denser neighborhoods.

Last week, consumer advocate Colorado Public Interest Research Group (CoPIRG) released an analysis that looks ahead to what cities need to do to keep up with growing EV interest. It estimates Denver could have up to 36,000 electric cars by 2030.

"We gotta build about 1,200 more electric charging stations in the next 15 years to be ready for the electric cars that are coming," said CoPIRG Director Danny Katz. Neighborhoods like Capitol Hill that lack a lot of business and rely heavily on street parking, he continued, will be "left behind" without help from the city.

Those stations he's talking about aren't your standard wall outlets. While EV owners can and do power up on standard 110 volt plugs, CoPIRG's report places emphasis on 220 volt power sources that get the job done more quickly.

Business interests have incentive to lead the way.

Mike Sickinger said he likes to take his Nissan Leaf to Lowry Beer Garden specifically because they offer EV-only spaces. And he's not the only one.

Joe Vostrejs — co-founder of City Street Investors, which owns the Lowry Beer Garden building — told Denverite those spots are always in use.

"The idea behind that is to attract them to our place so that they’ll shop at our stores and drink at our restaurants," he said, "we’ve built up a lot of regulars."

Beyond bringing in people like Sickinger angling for beer and easy parking, Vostrejs said he suspects the Lowry businesses get a lot of EV owners who live in apartments nearby and don't have access to a garage.

"If you don’t have a garage," he said, "having an electric car is kind of a challenge."

That's the very problem people like Katz are trying to solve in other parts of town.

"For a residential area," like Capitol Hill, he said, "there's less of an opportunity to make some money," and therefore less of a chance someone like Vostrejs might add to the existing infrastructure.

The other thing Vostrejs has going for his properties is actual parking spaces. It's a less straightforward proposition for urban neighborhoods that are already strapped for space.

According to a city spokesperson, about half of Denver's existing charging stations have been installed by private interests. Many of the city-built stations are in parking lots at public buildings.

Installing stations on the street is a more complicated matter.

CoPIRG's infrastructure analysis offers a few real-world solutions for EV street parking.

New Orleans, for instance, allows residents to install their own stations on the street in front of their homes. Residents are responsible for footing the bill, plus a $300 permitting fee. Seattle, too, has begun a pilot program allowing residents to permit and install stations on public roads, though those are only allowed in front of multi-family homes. London and Los Angeles have begun experimenting with outlets built into existing streetlights.

Each of these attempts first had to find support from local governments to move forward. Execution was only possible by coordinating multiple agencies.

Mike Salisbury, Denver's transportation energy lead, told Denverite the city would have to similarly coordinate stakeholders to find a working solution. Public works, he said, run the streets. Neighborhood groups will have to be consulted to make sure they actually want charging. In a place like Capitol Hill, he said, residents might revolt if EV efforts complicate the already difficult parking situation. If the city tried to plug into streetlights his department would also have to work with Xcel Energy, since they own all of them.

It's all a matter of finding the unique configuration that will work for each neighborhood, he said.

So far, Denver has installed a single curbside charging station on 14th Avenue by the City and County Building.

"It's just a first step," Salisbury said, "an initial demonstration."

Next steps would probably target the Central Business District, where the city might get more bang for its buck, but Denver has yet to compile a comprehensive plan of attack.

The city has produced its own study, but like CoPIRG's, it's more of a look at the lay of the land. Their report also pushes for a government-led policy to supply multi-family homes with power stations and for a new "public" funding source be developed.

"It's still pretty cutting edge," Salisbury said. For now, Denverites will just have to wait and see.