As demand for housing rises, people are trying out new ways to live together -- and they're not always obeying the law when they do it in Denver.

City rules set strict limits on how people use their homes. For example, no more than four unrelated adults can live together in a single apartment. The limit's even lower -- two unrelated adults, plus their relatives -- for single-family homes.

So, it's probably not surprising that the city was unprepared for the idea of the Beloved Community Village -- a collection of tiny homes that now sits on a lot at 38th and Walnut, housing nearly 20 people who have experienced homelessness. Building it required months of negotiations and nitty-gritty legal work.

Meanwhile, the city also has wrestled with other questions of group living. What rules should apply to artists who live together in studios? What about for nonprofits that want to build new homeless shelters -- a difficult task under the current rules?

"Any city that has rising land values is going to have more residents looking for ways to spread more costs around for more people," said senior city planner Andrew Webb.

In response, he and his colleagues are taking on a project that could open the door for alternative living models in Denver. They're pulling together a group that could propose significant changes to city law later this year. It's set to include artists, advocates, neighborhood groups and others.

"The idea here is to hear from community members, what’s working for you — what has changed in our society in the way that we live that the code needs to be updated to reflect," he said.

Tiny home villages could be a centerpiece.

The city and organizers used a legal workaround to get the first village built -- but the result is that the village is a "temporary" land use that can only exist in one place for six months.

"Anyone trying to do that … we would be kind of reinventing the wheel every time, in terms of our analysis. The neighborhood wouldn’t have any predictability," said planning spokeswoman Andrea Burns.

City staff now will consider creating a permanent status for villages. That wouldn't just allow them to stay in one place for a longer period of time -- it also could define how a village should look.

How big should the units be? What kind of facilities would they need? These are the kinds of questions that several cities are already asking, Burns said.

The Beloved tiny-home group also will push for some limitations on villages. Cole Chandler, an organizer, said that they only want nonprofits to be allowed to run the villages.

"The reason for that is we don’t want developers coming in and selling $80,000 tiny homes," he explained.

Meanwhile, the tiny village residents are trying to get an extension so that their village doesn't have to move a second time this July. The group also is working on a second village that could be sited at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church.

Other topics:

The process also could include a review of the rules about shelter construction.

"Right now, there are requirements in the code for how far apart shelters need to be from one another, how many shelter-type uses can be in one city council district," Webb said.

"Are we allowing service providers to provide the shelter beds to meet the need?"

Other topics will include community corrections facilities -- of which construction hasn't been allowed. Live-work art and performance spaces are also under consideration as an “emerging” use not considered in the code — though they’ve been around quite a while longer than the idea of tiny-home villages.

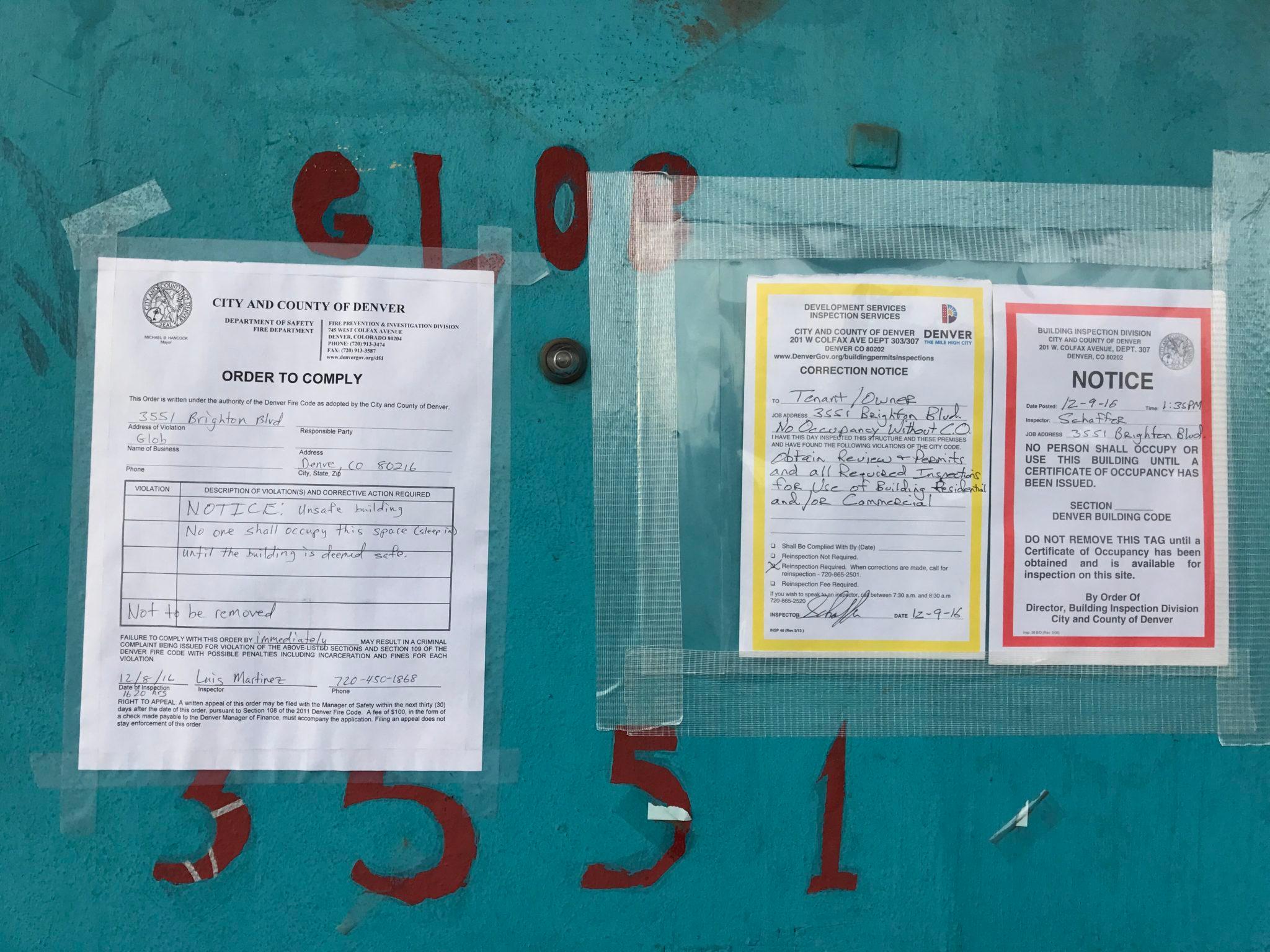

What has emerged is a sense of urgency. In the weeks immediately following the deadly Ghost Ship fire in Oakland, the city of Denver inspected DIY spaces across the city in response to tips and complaints. Rhinoceropolis and Glob, the Brighton Boulevard sister spaces that abruptly shut down after a surprise inspection, had been operating for about a decade and inspected by the city once a year for five years leading up to eviction.

In the year that followed, artists have scrambled to secure their live-work spaces as the city struggles to provide adequate support. The problem: cash-strapped artists usually can’t afford the work required to get their spaces up to code.

The leaseholders at Rhinoceropolis and Glob have been tight-lipped about the process, as have other artists fighting for housing who worry that speaking publicly could jeopardize their efforts. We do know that the city asked at least one representative of Rhino and Glob to join Group Living Advisory Committee.

It’s unclear right now how the outcome of this process might affect the requirements for the Safe Creative Spaces Fund or the Safe Occupancy Program, both of which were created to help artists get their live-work spaces up to code.

The Denver City Council would have to approve significant code changes. That could happen late in 2018.