Maria Uribe was visiting a classroom to certify a teacher last year when a little girl entered the room in tears. The four-year-old, who normally would be happily chattering away, sat quietly in the corner of the room by herself. The colorful ribbons that normally adorned her hair were absent.

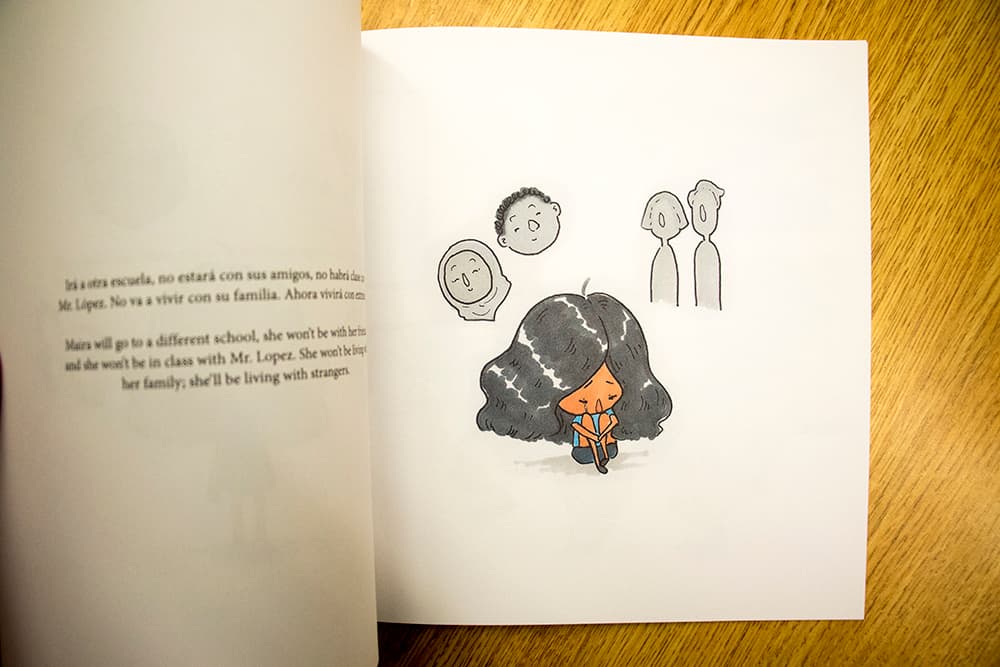

When Uribe asked the teacher candidate what was going on, she learned that the girl's mother and grandmother had entered deportation proceedings. Her father had recently also been deported. The girl, a citizen, would now go to live with strangers. Uribe said she had to leave the room.

"I sat in my car and I cried, and I cried, and I cried and I said, 'I have to do something.'" Sitting there with tears streaming down her face, she called her friend and collaborator, Sally Nathenson-Mejia. "I said, 'Sally, I think the best thing to deal with this is to write a book.'"

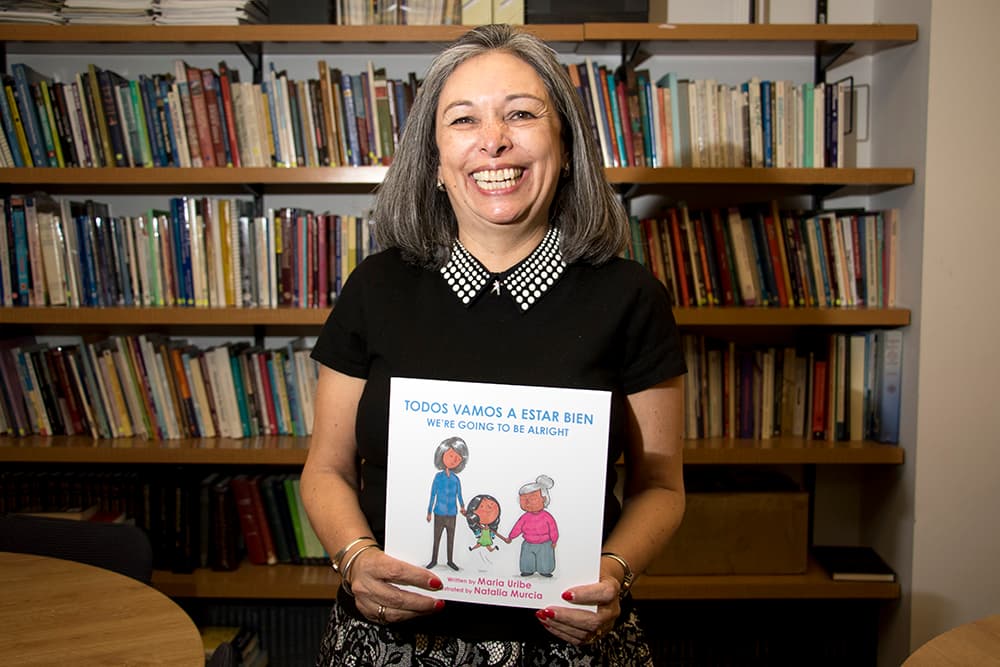

This month Uribe, Nathenson-Mejia and illustrator Natalia Murcia Gutiérrez celebrated a coming-out for their new children's book, "Todos Vamos A Estar Bien" or "We're Going To Be Alright," which tells the story of that day.

Uribe's hope for her illustrated children's book, which shows the struggle of a little girl whose parents will be deported, is to show kids dealing with these situations that they are not alone.

While Uribe now trains educators at the University of Colorado Denver, she spent 22 years working in a multitude of jobs (including as principal) at a Denver elementary school. This was not the first time she'd watched a student cope with family deportation, but this time, she said, was the last straw.

"It has happened for so long and it's time to do something," she said, thinking back at her long career working with kids.

She recalled one time in a cafeteria when she heard one first-grader ask another if his parents were "wetbacks," listening in amazement to the kids talk in depth about their family's legal statuses. She remembered a kindergarten student who wanted to commit suicide.

This kind of thing always brings Uribe to tears.

"That is just devastating," she said. "Sometimes as adults we don’t see what we're doing. ... It’s the reality of kids and we forget about them."

A study of 2009-2013 census data by the American Immigration Council estimated that a little more than 4 million children nationwide have at least one undocumented parent. Between 2011 and 2013, the report says, a half a million kids witnessed "the apprehension, detention, and deportation of at least one parent."

Colorado Public Radio has reported that deportations in Colorado and Wyoming since the 2016 election are nearly numerous as they were in 2013, a substantial hike from a lull during Obama's last two years in office.

Uribe has been touring her book to area schools since late last year. She thinks she's read it to nearly 600 kids. When she presents for a school with a lot of Spanish-speakers, she said, the book is often met with a receptive audience. That happened just last week.

"There were so many kids who related to the story," Uribe recalled. "One of the kids ... she said, 'That happened to me.' It was very emotional."

While it's sad that there are so many young people who know this reality, she said, "They can see that they're not by themselves."

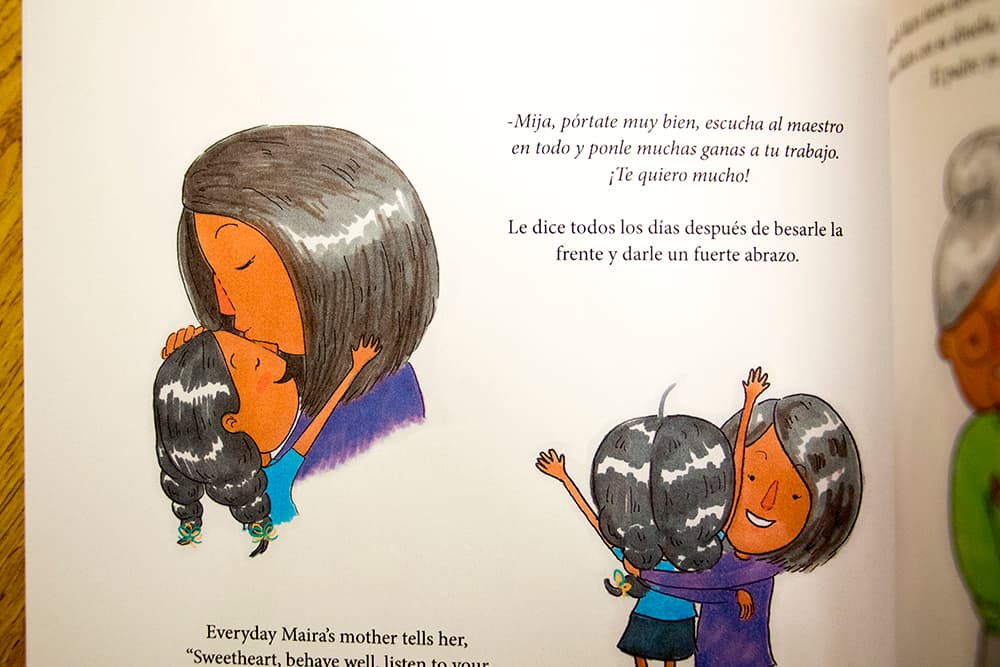

Her story is a simple one: A young lady has a loving family, but one day she comes to school in tears with bad news. It ends with the girl sitting with her teacher and classmates in a circle holding hands.

Like recent fights over legal status for people with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status, Uribe can do little else than recognize a difficult situation. While the decision makers on these issues navigate partisan politics in Washington, the rest of the country can only watch and wait.

This leaves Uribe's ending as a kind of loose end. The story isn't over; there isn't much resolution for her character. Except, that is, the comfort of a teacher.

As an educator of educators, Uribe said her audience is two-prong. Beyond children, she hopes the book will help teachers deal with these kinds of situations. They, in turn, can continue to help struggling students after the book is back on the classroom shelf.

Many kids see this as a sad story, Uribe said, but one second grader understood her deeper message.

"I think that book is actually happy," she recalled him telling her. "The teacher holds hands with everybody and he gives them happiness."

Even with few ways to act on behalf of these young kids, Uribe hopes small things like a held hand or a story might still make a difference.