Until recently, an elementary school in Whittier flew a banner with the name of a man well known in north Denver: Albus Brooks, the president of the Denver City Council.

Brooks had paid $500 for the privilege by sponsoring a fundraiser for the school's PTA. Actually, the city paid -- the money came from the city budget.

Now, it's the subject of a campaign finance complaint. The nonprofit Strengthening Democracy Colorado argues that Brooks wrongfully used the city money to boost his own public image and, indirectly, his campaign for re-election. Brooks counters that the banner didn't say a word about voting and that his intention was simply to support a worthy cause, calling it a "weak story."

This may seem like small ball, but the argument poses a big question for city officials: Where's the line between advertising yourself and advertising your campaign? And should the city pay for either?

In fact, what Brooks did was far from uncommon.

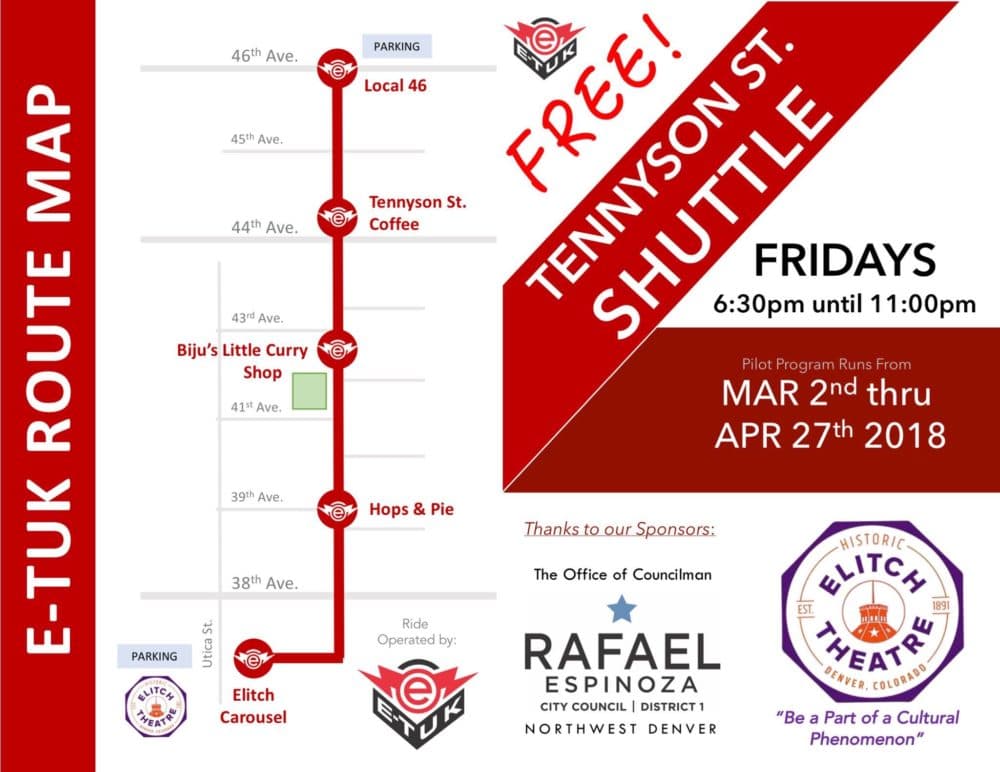

Councilman Rafael Espinoza spent $2,500 of city money to sponsor an electric-vehicle shuttle service, promoting his name and logo. Council members also have put their names on magnets, markers and reusable grocery bags, not to mention the name recognition they've gained by supporting various community events.

In every case, the elected officials said that they're spending their portion of the city budget to further the public good and engage their constituents, just as they're meant to. But to Jason Legg, the attorney who filed the complaint against Brooks, the spending raises larger concerns about whether incumbents are gaining an advantage with public dollars.

"The principle of the matter is you cannot blur the use of public resources for your campaign," said Legg, co-founder of Strengthening Democracy Colorado. And, asked about the donations, some council members said they would reconsider how they spent their office budgets.

In each of these cases, though, the council members did not cross a "bright line" described by an ethics expert: None mentioned elections or voting.

This all started with a fundraiser.

In 2017, a member of the Whittier PTA contacted Brooks, who represents the area. The organization was trying to raise $15,000 to "keep music at our school," among other goals, according to public records released by Strengthening Democracy Colorado.

Large donations to the fundraiser come with a perk: Sponsors' logos would appear on banners hanging near the school.

Brooks' office agreed to help out, cutting a check for $500 for a fundraiser concert.

The money came from Brooks' city council office budget. The council members use their budgets to pay for staff and office expenses. The leftovers return to the city's general budget, or council members can spend the remainder to advance the public good.

Soon afterward, a blue banner appeared on a railing near an entrance to the school. It featured the words "ALBUS BROOKS" and "Connecting Diverse Communities." It appeared alongside banners for dentists, lawyers and real estate brokers.

Brooks said that the banner was clearly unrelated to the May 2019 election. "It’s not our campaign banner. It’s not our 'Vote for,' it’s not our 'Support Albus Brooks,'" he told Denverite. "It’s our typical logo."

Brooks' office regularly donates to charitable causes, including the Whittier school, he said. Donations are allowed under city rules, and he reported the $500 check to the city government as required. Brooks had donated to the Whittier PTA in the past, according to the letter, and regularly supports community groups.

"We don’t give to be recognized. We give because that school right there serves the poorest kids in the entire city," he said. (About 90 percent of Whittier's students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measure of poverty among students, according to schools data.)

The school's principal did not respond to two requests for comment.

"There’s no examples of precedents of other people doing this. I don’t have a case to point to," Legg said. "Everybody else just knows that’s absurd."

In fact, other council members have reported similar spending.

Council members have used the city money to support schools, charitable programs and the municipal band -- sometimes getting a bit of name recognition in return.

Kendra Black, Paul Kashmann, Wayne New and Mary Beth Susman all are listed as "silver sponsors" of a local transportation conference, having spent $500 each of office funds.

"The fact that we can use our budgets to help community efforts is a really nice thing to be able to do," Susman said. "It never occurred to me that it could be a campaign thing ... You're working as a city councilperson who is benefiting community events. It comes out of your office funds, and you manage your funds."

Espinoza, who represents northwest Denver, paid $2,500 to sponsor a free electric transportation shuttle on Tennyson Street. Signs at shuttle stops included his name and district number.

"Ours is honestly sort of borderline," he said. "The idea of circulators and shuttles as transit alternatives, free ones, are part of the thing that I would promote, that I want to see us do as a city."

Council members also use city money to produce branded giveaway items, as Councilwoman At-large Debbie Ortega did with reusable grocery bags, which are meant to reduce people's use of plastic bags, according to her office staff. And Espinoza ordered permanent markers that say, "I sketched ideas with Councilman Espinoza."

He acknowledged that the spending could boost his profile, but he said that the real value is that it can involve people in city government.

"To me, it’s important because such few people actually participate in municipal elections, that I want them to sort of recognize — you’re in the city. You have representation there. You should have at least the same amount of involvement," he said. "It doesn’t get any more personal to you."

Susman was split on the issue. "If the optics are wrong, then maybe we should (just) put 'City Council District 5,'" she said.

In other cases, council members use their own money on promotional materials: Black paid personally to produce hats for staff members in a transportation study of the Hampden area. The hats read "HAT," for Hampden Advisory Team.

What's next?

The complaint against Brooks does not bring particularly serious consequences. If an administrative law judge finds it has merit, Brooks could have to reimburse the city for the $500 sponsorship, Legg said. A hearing officer could take up the case next month.

He argued that Brooks should at least have included more useful information, like a link to a city website, if it was not a campaign banner.

"Arguably, that’s a legitimate thing, but the manner in which he did it clearly was more about brand promotion for himself. There’s no information that can be used there on that banner," Legg said.

Cases where there's a city logo and clearer connections to the city government alongside an elected official's name, he said, are far more acceptable.

Denverite also asked Amanda Gonzalez, the executive director of Common Cause Colorado, about the argument.

"Nationally, elected officials using government funds in a way that elevates that official’s public profile is somewhat common," she wrote in an email.

"Sometimes these activities can be positive; constituent contact is important and constituents should have ready access to information about what their elected officials are working on. The downside, however, is that the use of government funds to raise an official’s profile gives incumbents an electoral advantage over electoral challengers."

One of the "bright lines," she added, is the question of whether the materials referenced elections or campaigns.

Denverite found only one example of that: Councilman New's office recently sent a newsletter that included an announcement of his re-election bid. Realizing the potential mistake, they sent a second edition with an apology.

New reimbursed the city for the email newsletter's cost and his staff's time, according to his office. In all, it came to $30.70.

Have you seen an elected official in Denver or elsewhere promoting a campaign with public funds? Contact me.