David Trujillo paused for a moment from his work late one afternoon. He leaned against his pickup truck, loaded with logs and scrap that he had collected in his route through northeast Denver.

Here, at the edge of Elyria-Swansea, he saw the future: rows of orange construction cones and fences where the demolition crews had started their work. He was staring at the frontier, where the beginning of a huge city project met the edges of a neighborhood that has changed relatively little.

"It won't be long," he said. "I've been here 40-odd years."

Looking across Brighton Boulevard, Trujillo pointed out the empty lots where the 7-Eleven and the El Duranguense grocery store -- two of the area's only convenient food options -- and the duplexes and the motel for bachelors all used to be.

The buildings were demolished recently ahead of the redevelopment and expansion of the National Western Stock Show, where cattle buyers have traded animals for a century. The city and its partners plan to spend nearly $800 million to turn it into a 250-acre, year-round center for culture and agriculture.

And as construction of the new National Western Center finally gets underway, the signs of change in Elyria-Swansea are growing stronger, too.

The neighborhood's residents are bracing for years of construction at their border. They're noticing more real-estate agents patrolling their streets. And they're working, too, to make sure that the city delivers on its promises that they'll see some benefits as their patch of the city is reinvented.

For Trujillo, 75, change could come even sooner: He'll be moving out of the neighborhood by June 1, he explained, because his landlord has decided to sell the place.

The National Western project has been building steam for years now.

It has all the steering committees and public meetings and launch parties that you'd expect from a partnership of some of the state's biggest players: the city of Denver, Colorado State University and the National Western Stock Show Association.

But if you haven't driven up Brighton Boulevard lately, you might be surprised to see that work already has started. And these initial phases won't finish until 2024 or later.

"We’re getting started. We’re in the demo phase now," said Jenna Espinoza, a spokesperson for the project. “That’s kind of the kickoff on our construction, and it just gets bigger from there.”

The final vision of the National Western Center still hasn't come into full focus. Much of the work being done today is to prepare the site in broad strokes, including utilities and pads for big new buildings.

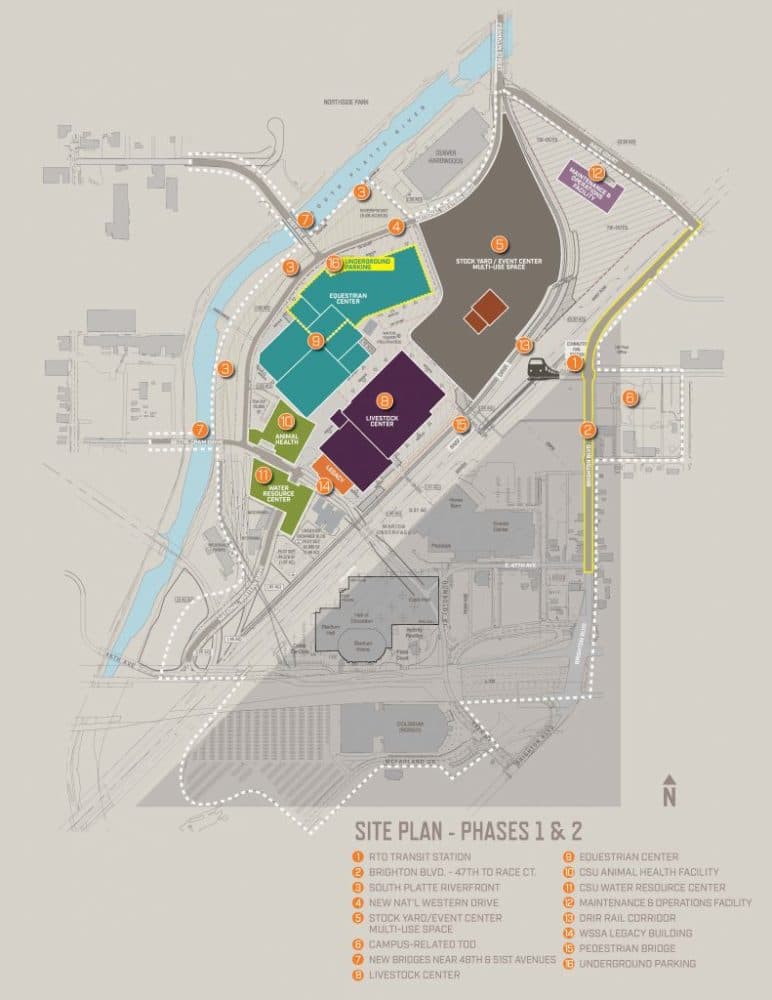

But what's obvious is that the new plan will open more than 100 acres for development and bring brand new transportation connections to one of the most isolated neighborhoods in Denver.

National Western will reconnect Elyria-Swansea.

Until now, Elyria-Swansea has been bordered by the parking lots, cattle pens and warehouse space at the back of the National Western campus. Rail lines divide the neighborhood, and Interstate 70 looms on concrete stilts to the south. And all of that will change with NWC and other projects.

The new campus will bring upgrades to Brighton Boulevard, making it far safer to walk or bike from the River North district to Elyria-Swansea.

RTD also plans to open a rail station at 48th and Brighton on the under-construction N Line, which could separately bring dense transit-oriented development right to the edge of Elyria-Swansea, according to NWC plans.

Meanwhile, two new bridges over the South Platte River will deliver access to the northwest, and the riverfront itself could be opened up with trails and other amenities.

The campus itself will include a livestock center, equestrian center, animal health building and a water resource center along the South Platte. Later additions could include an expo hall and a new arena. Some of the existing buildings will be preserved, including the arena on the south side that was built in 1909.

Combined with the I-70 rebuild and new flood controls, it's a mind-boggling amount of construction -- so much so that many residents can't keep up.

"You hear just different things," said Herrera, standing in front of his parents' ranch house. Some people told us that they'd heard that National Western would be torn down altogether, and they wondered how many more homes would be demolished. Others were simply getting overloaded.

The city's information campaign has included monthly meetings, community liaisons, text message programs and more. (You can sign up for information at the website.)

But, for Herrera, one thing was obvious.

"Once they told us about the construction, the prices started going up," he said.

And his parents are likely to take an offer. They want to move east toward the plains town of Limon, returning to their rural lifestyle. "I can't understand why they want to leave," he said.

Adam Waggoner, a real-estate agent, told Denverite that he was shocked by the number of buyers who flocked to a recent sale in the neighborhood.

"My phone was just ringing off the hook. I knew there’d be interest, but not quite the level that we got," he said.

He had expected that buyers would be deterred by the years of construction ahead. And Elyria-Swansea, one of the city's lowest-income neighborhoods, already is subject to the pollution of highway traffic and the smell of the Purina pet-food factory to the south.

And yet the house at 47th and Race had more than 150 showings in a single weekend, and a bidding war drove its asking price of $325,000 up to a $387,000 sale, Waggoner said.

It was unique for its large lot and its 3,000 square feet of interior space, but the sale has quickly become known locally as the "$400,000 house," a surprising sum alongside the $200,000 sales that are far more common.

"I think the conventional wisdom that many of those areas weren’t as attractive to the buyer pool was completely thrown out the window," Waggoner said.

But the neighborhood hasn't seen many scrapes and slot homes.

An afternoon walk through the neighborhood reveals an incredible mix of homes, from pre-1900 houses to duplexes that are under renovation. Kids race through the streets on scooters and skateboards, while neighbors chat amiably at their fences.

Elyria-Swansea today has a population of about 7,000, and 83 percent are Latino. In all, Latino families make up 60 percent of the neighborhood's homeowners -- more than any other neighborhood except Westwood, according to 2015 data from Shift Research Lab. Black families make up another 10 percent.

Armando Payan, a real-estate broker who grew up in the neighborhood, said that gentrification hasn't quite arrived yet.

"I think it’s still to come," he said. " ... Right now, people are hanging on (to their homes). You don’t see very much inventory at all."

Waggoner agreed. There are relatively few homes for sale citywide, and Elyria-Swansea might be even tighter, he said.

"They’re a little reluctant to see the neighborhood changing and turning over," Waggoner said. His employer, Generator Real Estate, has worked with the nonprofit GrowHaus in the area.

But Ruby Arrieta, a 27-year-old in tech support, said the pace of change seems to be intensifying. She's met new residents moving in from Boulder and beyond. Some of them have started calling the police on "suspicious vehicles" or with noise complaints about everyday events, she said.

"There's a lot of Hispanics around here," she said, pausing with her mother at the gate to the duplex the family owns. "They like music, birthdays, weddings."

Her family is going to stay -- "We've been here way too long," she said. But she already has seen renters leaving the neighborhood, and possibly the whole city, as rents creep higher.

How will National Western affect this equation?

For the next few years, there's the practical impact of construction. The demolition of the two food outlets -- 7-Eleven and the grocery -- was particularly stinging to some.

"It still blows me away ... They took two food outlets," said Nola Miguel of the Globeville, Elyria-Swansea Coalition Organization for Health and Housing Justice. She's also concerned about the new vacancy of buildings on the project's eastern edge, urging the city to move faster to reactivate the area.

"Everybody knows the effect of vacant homes on a neighborhood," she said. "It’s sort of like this 'change is coming' feeling, and not necessarily in a good way."

Espinoza, the city spokesperson, said that the project team was working to make sure that National Western serves the community in the long term. They're developing a plan that aims to determine "what the community wants and how/where it can incorporated" she wrote in an email to Denverite. The next meeting in that process will be scheduled in June.

The city also has partnered with CDOT on a $3.8 million project to upgrade some 250 local homes with protections from noise and sound associated with the I-70 project. There's also talk of creating land trusts that could keep homes affordable in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea and citywide.

And, in the long term, the NWC partners are considering creating Colorado's first "public market," which are meant to be permanent marketplaces for fresh produce and other goods, on the National Western campus.

As all that happens, Payan said, both the city and its residents need to figure out how to preserve what's great about Elyria-Swansea.

"For most of the residents that are there — we want to anchor in, we want to stay there," he said. "I tell people, why should I leave? Why can't I make my neighborhood better?"