The idea that changed Eric Glade’s life arrived on the rear end of an automobile.

He was driving through Denver on Interstate 25. It was March of 1979. And there it was: a bumper sticker, printed with a green mountain landscape similar to Colorado’s license plates, and containing one word:

“LAMM.”

It was an old campaign sticker for then-governor Dick Lamm. But in that moment, Glade’s 24-year-old brain saw something far beyond politics. For one brief moment, he connected to Colorado's prideful zeitgeist.

He thought: What if I put the word “NATIVE” on that bumper sticker instead?

“And there it is. That’s it,” he said in a recent interview at his home. Eventually, this traffic-inspired idea would become a part of Colorado's modern identity.

In the decades since that day on the Valley Highway, Glade's "NATIVE" stickers have been plastered on a million or more bumpers. His idea has spawned countless knockoffs, family tensions and a legal confrontation with Frontier Airlines. It landed Glade’s name in The New York Times and National Geographic.

It's also fueled an argument that burns just as hot today as it did 40 years ago.

The point of the sticker, quite obviously, is that the occupants of a vehicle were born here in Colorado, not like all those transplants. The fact that Eric Glad was himself a transplant did not slow him down.

“If you didn’t get it, then you don’t belong. It didn’t say ‘Colorado Native,’ or ‘I’m a native of Colorado.’ It just says ‘NATIVE.’”

He would go on to launch similar stickers in California and copyright the theme in five other other states, dreaming of a national empire of nativism. None, however, sold nearly as well as Colorado.

At first, though, nobody cared.

As soon as Glade got off the road that day in 1979, he grabbed a piece of cardboard and sketched a silhouette of the mountains and that one divisive word.

“I showed it to a few friends of mine. They thought, ‘Oh, whatever,’” Glade said. “My dad told me I’d be lucky to sell one. He didn’t think you could make money, except in the oil business.”

They didn’t see what Glade saw. Ironically, he had grown up in Utah. His father, a hard-gambling wildcat oilman, moved the family to Lakewood to chase the oil boom when Glade was 14.

Even as a kid, he had noticed a certain protectiveness in Colorado’s culture. “This was a really small town back then. Where I went to school (at Bear Creek High School), we used to hunt across the street,” he said.

And, already, growth was an issue.

Bear Creek had grown from a couple hundred students to some 1,200, he said, forcing it to move its graduation to Red Rocks. The oil boom had brought waves of new residents, especially from the north. Canadian oil executives were the butt of jokes that now are reserved for Texans and Californian programmers.

“God, there’s hardly anybody that grew up here,” Glade's friends would complain.

“Like it was a status symbol.”

Dick Lamm — the politician whose name was on the bumper sticker — was a perfect symbol of the backlash. In the '70s, he led the uprising that killed the Olympic Games that were planned for Colorado. In 1975, he became governor. And Eric Glade recognized that there was money to be made off that volatile combination of anger and pride.

“If I’d have been a native, it wouldn’t have hit me that way,” he said.

Now 63, he was recounting the story from an elk-hide draped couch at his home in Highlands Ranch, hair tied back in a ponytail, wearing a polo shirt printed with marlins, the walls adorned with the skulls and antlers of elk that he and his wife have killed with bows and arrows.

“Like, ‘Wow, these people are really kind of rabid about being a native,” he continued.

“So why not cater to that?”

He took his cardboard sketch and $90 from his job as an oil landman, and he filed an ad in the Rocky Mountain News: $2 for a sticker, $7 for a T-shirt. He didn't bother to print any of the product beforehand.

The money-stuffed envelopes arrived within days. Soon, he had $800, and he ordered an initial run of 500 screen-printed vinyl stickers from Good Decal Co. The quality of that first run was so high that many of the originals are still on the road, thanks largely to now-banned printing inks, according to his sister.

“I kept doing more runs,” and advertising them in the local papers, he said, “until it got pretty big, where I was up half the night shipping stickers to all different locations.”

He tried, too, to convince the state's heritage foundations to endorse the sticker. "My being born in Salt Lake City took some of the edge off my sales pitch," he told a newspaper reporter at the time.

Eventually, Glade got a call from a man named Robert Hatch, who tracked Glade down at the Bottle Hollow Resort in Utah, where he was out an oil job. He wanted 10,000 to sell at the Hatch chain of gift stores.

And that’s when everything changed. Soon, Glade was taking calls from head shops and record stores, with the strongest locations selling 100 stickers a month.

It was a wild time.

"We had some great hot-tub parties, from what I can remember of them," said Sandy Glade, Eric's sister. "All of a sudden, we just had all this money. It was a good time back then."

Eric was renting limousines and a house next to Willie Nelson's, he claimed, and doing things that newly rich oil-and-sticker guys did in Denver.

"It was the ‘80s," he said. "I had money, I was having fun. I don’t have any of that money left. Easy come, easy go."

Meanwhile, it felt as if someone had stuck the sticker onto the collective consciousness. Eric Glade was trading friendly blows with a sticker-printing rival.

"So, all of these stickers started going back and forth: 'Who cares,' 'I care,' 'We care,' 'Nobody cares,'" he said. There were "Alien" stickers, too, and "Naive," and "Semi-Native."

Letters were pouring into the newspapers, and the stickers became a trope for journalists. "The next thing you know, he’s in Time Magazine, and LIFE Magazine, The New York Times, National Geographic," Sandy Glade said.

It boiled down to the same complaints you hear now: Longtime residents felt they were being drowned out, washed away, while their new neighbors felt downright unwelcome.

And, actually, we should note that there's some debate about whether Glade was truly the first to make the sticker.

Accounts in the Washington Post and Rocky Mountain Magazine trace the sticker to Boulder resident Robert Shaver, who reportedly printed them in 1978 as a perk for the short-lived Colorado Native Society. (Other contemporaneous accounts credit Glade.)

That same society denied Glade an honorary membership in 1979, as he told the Rocky magazine. No matter: He won the copyright to the NATIVE sticker in 1981, and was credited in National Geographic in 1984 as starting "The Great Bumper Sticker War."

"I just followed it the way it went — sitting on the sideline, watching people chew each other up — 'Oh, you arrogant son of a bitch,'" he said.

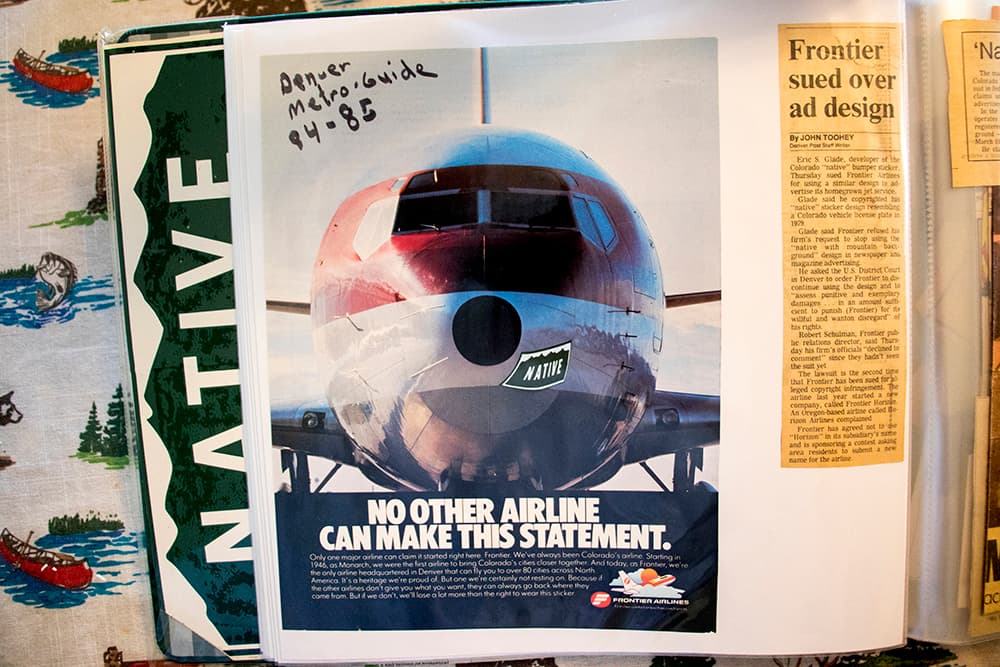

He had sold 75,000 stickers within a few years, as he told a reporter at the time, while the Colorado Native Society leveled off around 500 members. And Glade fiercely protected his slice, even suing Frontier Airlines for their use of the image. He won an undisclosed settlement, he said.

All the conflict was good for business, and Glade tried to capitalize even further on it.

"You look at the national scale, it’s the same thing too. People really don’t like immigrants," he said. "I did a sticker for a while, and it was mean-spirited -- and it said, 'The pool is full' — and the pool was the United States."

Personally, he adopts more of a "live and let live" philosophy.

"But I knew it would sell," he said.

"But I've also found over the years — the mean stuff, you can make a fast buck on it, but it’s not long-lived."

The craze died with the oil bust.

The price of oil declined through the early 1980s before a dramatic crash in 1986. The bust was so bad that Denver's population dropped by about 5 percent in the decade

Meanwhile, the sticker business went largely dormant. It's impossible to say whether people were simply burned out on the debate -- or maybe if the distinction became less important when there were fewer transplants.

"It just kind of went dormant," said Sandy Glade. "It sat in the basement."

"I could have made a lot of money at it, but my mind wasn't there," Eric Glade said.

He wandered through a few more jobs, including as a hunting outfitter -- he's a Westerner at heart, following the "cowboy way," he said. He eventually met his current wife while painting her house.

Along the way, he contracted bubonic plague, and nearly died of a "widowmaker heart blockage." Now, he's building a house in the mountains, seeking some of the peace and quiet that perhaps all those natives valued.

"I think I've earned my keep. I've earned my place," he said.

Meanwhile, the stickers have kept selling. The Glades' mother watched over the business through most of the '90s, until she and Sandy Glade bought out the rights in 1999.

Today, she sells a variety of stickers through Native-Ink -- some of them anti-Hillary, some of them pro-Trump, almost all of them on the same mountainous background. ("Obamageddon," anyone?) Her brother looks on with some bitterness, complaining that she's jumping on hot topics instead of striving for the classics.

"She killed the golden goose. Her and my mother should be sitting pretty off of what I gave them to work with. She should have worked at it," he said.

But didn't he give up too, I asked?

"It didn’t hold my interest long enough. I did too many other things," he replied.

Sandy Glade says the business is still growing, and she thinks that she could push it even further. She sells thousands of Native stickers each year, accounting for 70 percent of her sales.

"The 'Native' will always be the bestseller," she said. "It's still as valid as it ever was."

And then, in close second, there's this one: "Not a native, but I got here as soon as I could."