Lisa Suydam waited just before 5 p.m. on a warm winter Friday, wondering where her husband was.

He usually left work just after 4, and the bike ride home from Golden rarely took more than 30 minutes. They were planning to have an early date at a neighborhood brewery — maybe Little Machine or Seedstock.

She knew that something could have gone wrong. She was “used to the accidents,” as she puts it now. Their son and daughter had already been struck by automobiles while cycling. “I’ve just always had a bad feeling that accidents are going to happen.”

And so she reached for phone, and turned on the app that Gary had installed — the one that tracked his rides in realtime for her.

“I pulled out my phone,” she recalls. “It showed him at St. Anthony’s Hospital. And I said, ‘Oh, that's not good.’”

Her gut was right.

Gary Suydam was the victim of a traffic crash on Jan. 27, 2017.

It was shocking and yet somehow unsurprising in its cruelty. It went unnoticed by the public. No media outlet mentioned the case until ten months later, when the court case concluded and the district attorney sent a press release.

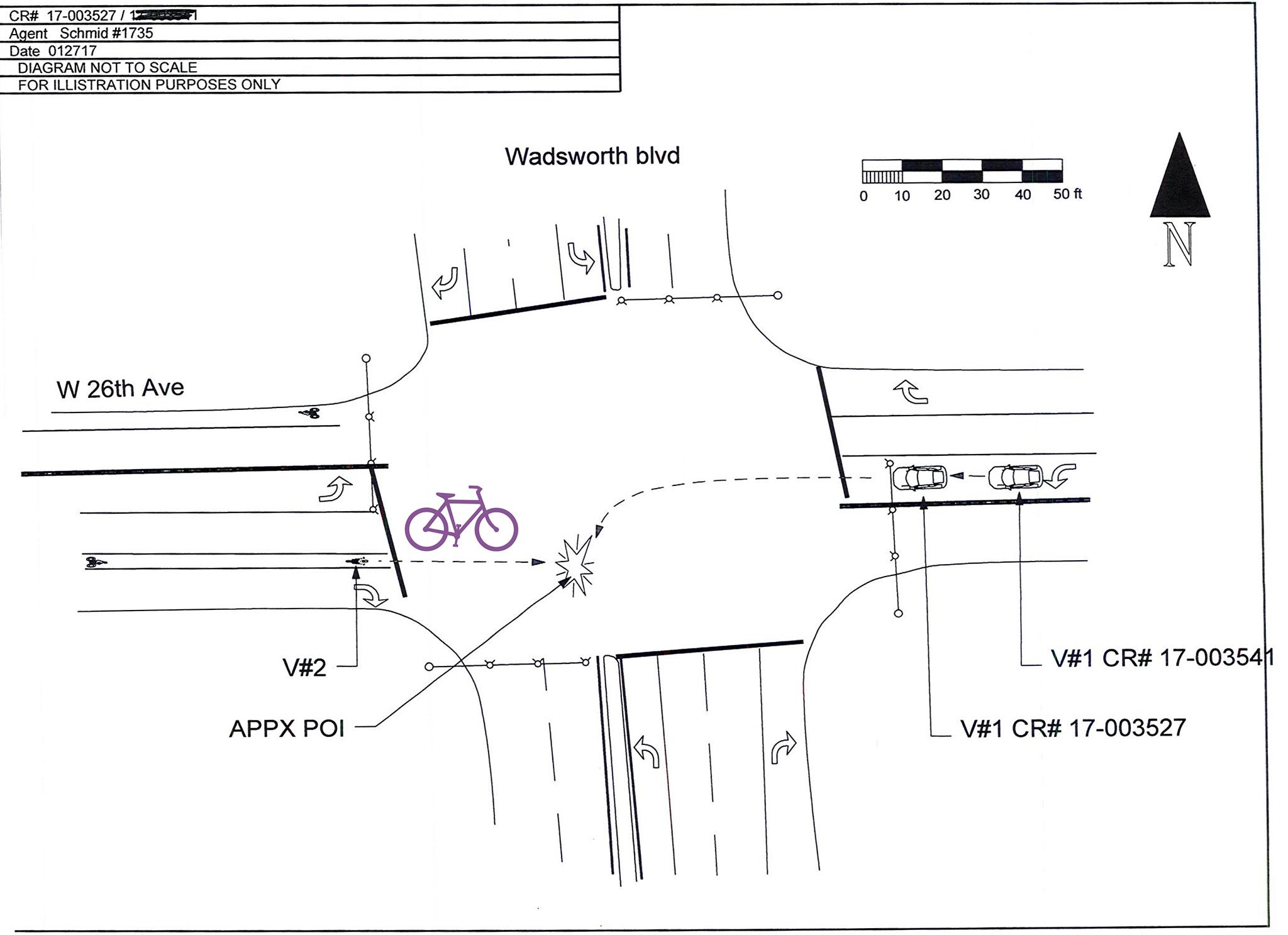

Even in the clinical language of the justice system, the details were gruesome: A driver cut off a cyclist on 26th Avenue, knocking him to the ground. Then a second driver ran him over and fled the scene, leaving him permanently paralyzed.

Up close, the story unfolds into something more: a tragedy, a moment of distraction that changed a man's life and a blueprint of the danger that bicyclists face -- even when they do everything right.

Gary, now 52, really became a cyclist when his son bought him a road-bike frame. Soon, he was riding to the Denver Tech Center for work.

“It was about 16 miles, and you know, the first few times, it hurt," he says in an interview. But he took most of the journey on the Cherry Creek Trail — a beloved route in Denver where bicyclists don’t have to compete for space with automobiles.

“I just watched the ground disappear under the bike and enjoyed it. Yeah, I didn't think about work, I didn't think about other issues -- anything, really.” Suydam says. “I just cleared my head.”

By the time he hit his 50s, it was a lifestyle.

He drove his car to work fewer than 10 times in the two years before the crash. Being a computer programmer, he even used an algorithm to plot a route that hit 25 different promotional booths during his commute on Bike to Work Day.

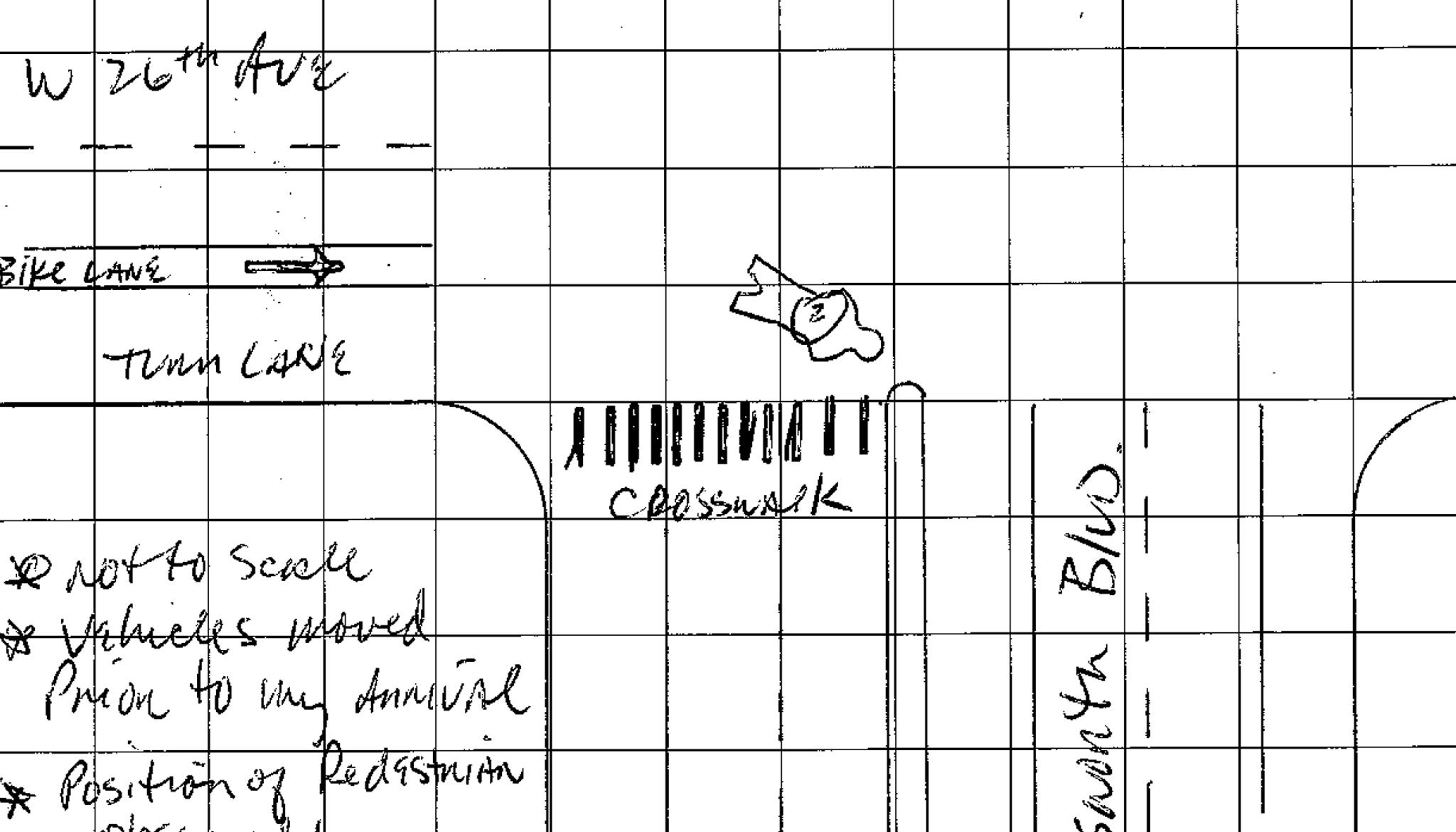

One of his regular routes ran along 26th Avenue, part of a patchwork of bike-friendly roads in the western Denver metro. With only a couple traffic lanes and a lower speed limit, it's one of a few routes preferred by cyclists.

On a typical day, Gary could do it in less than 30 minutes -- almost as fast as a car.

The crash happened at 4:32 p.m., according to the police report.

“You know, it's good therapy to talk about it as often as I can,” Gary says now. “It's still tough. Luckily, I don't remember much about the crash -- just everything since."

That Friday afternoon, he rode beneath a cloudless sky on dry pavement. The sun was sinking toward the mountains behind him, but it wouldn’t set for another 45 minutes. He rode in the bike lane, cruising downhill. Through his cycling glasses, he saw the traffic signal lit green at Wadsworth Boulevard.

The impact erased the details of what came next.

“I remember, one car turned in front of me. I remember reaching for the handbrake, probably saying, 'Oh, shit,’” he says, laughing a bit at his own language.

Afterward, he couldn’t remember whether he had even gone to work that day. But the police officer’s report lays it out — the mundane mistake of one driver, the apparent cruel impatience of another, all within seconds.

As Gary approached from the west, a white Mercedes SUV idled on the east side of the intersection. Its driver, Chelsey Brewer, just shy of her 38th birthday, was waiting for her chance to turn left.

She faced a flashing yellow arrow, according to multiple witnesses — a sign that she could proceed when the road was clear. She was sober, by all accounts. But apparently she didn’t see Gary. Her turn took her across his path. A passenger said, "Stop."

And Gary's bicycle struck the side of the car.

Gary landed in the crosswalk, according to witnesses. Brewer stopped. And then the second car came — a silver Honda CRV. Its driver, 63-year-old Stephen Tecmire, was following close behind the Mercedes.

He ran over Gary’s injured body, according to witnesses. The CRV’s wheel caught the injured man and his Mondial Tommaso bicycle, dragging it along for a few feet before leaving the scene. The car caught him by his head and neck, according to the Suydams.

"I think they knew they went over me. They should have known they went over me. And an eyewitness said it looked like the car drove over a boulder,” Gary says, breath growing shallow. “I have no doubt that the helmet saved my life.”

Tecmire stopped nearby, then left the scene. When officers located him, they found a tuft of hair in his car’s undercarriage. He told them he didn't think he was involved. He had kept driving because others had already stopped to help, he said.

He added: "Well, there was a lot of sun glare."

Chelsey Brewer told investigators that she had a green arrow and the right of way, according to a police report. But witnesses outside the car agreed that she did not.

She did not respond to phone calls requesting comment, or to a message left with a friend at her former residence. Tecmire, the second driver, is in prison.

Later, a prosecutor would say that Suydam was a nearly perfect victim.

That's because he “did nothing wrong,” Gary says.

“I chose the road specifically because it had a bike lane. I was going through on a green light. I had a light on the front and back -- white and red. I was wearing a helmet,” he said. “There was nothing I could have done to change the situation.”

But the situation was in some ways unsurprising. Nationwide, more than 1,000 cyclists died in crashes in 2015, and they face a higher risk of injury and death than people in automobiles, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

In fact, cyclists like Gary -- the bike-to-work pioneers -- may be especially vulnerable. On suburban roads with fewer bicycles, drivers can become almost blind to them.

"If they never see a bicyclist, and they miss it the one time they’re there, that’s a pretty dangerous scenario," said David Hurwitz, a transportation researcher at Oregon State University.

He has specifically studied "flashing yellow arrow" intersections, like the one where Suydam was hit. When his team put drivers in simulators, the drivers devoted most of their attention to traffic signals and oncoming automobiles -- and much less to pedestrians.

That same danger may extend to bikes, according to some longtime cycling advocates.

"The driver’s looking for a gap in the automobile traffic, and I just think that’s a recipe for disaster," said Gary Hardy, a Lakewood resident who has been biking to work for 50 years.

But flashing arrows can move traffic more efficiently, and their design standards do account for bikes and pedestrians, Hurwitz said.

Still, the overwhelming theme is obvious: Human error can erase the benefits of a bike lane.

"I think I have more concern now than at any time prior," Hardy said. "... Traffic congestion is worse. The vehicles are much larger. And our driving behavior has gotten worse."

In another study, two-thirds of drivers failed to check bike lanes before crossing them in a right-hand turn, Hurwitz said. And when they did see a cyclist, some still failed to "cognitively process" the sight.

"They looked at it, but they didn't see it," Hurwitz said.

Moreover, researchers have found that drivers who recognize cyclists still misjudge their speed and location, and that they wrongfully expect that bicycles will yield to them.

As a result, some cyclists believe it's not always safest to ride on the shoulder. When Hardy takes 26th Avenue eastbound, he takes the main traffic lane and rides fast enough to keep up with cars, a "defensive measure" to make himself more visible. (State law says that bikes need to stay right unless they can keep pace with traffic, but cyclists can ride anywhere they're not prohibited.)

But bike lanes are still important safety features, he and others said, especially because they make newcomers more comfortable. Both Wheat Ridge and Lakewood have created new plans to encourage cycling and create bike infrastructure.

"Some bikers you label as fearless, and there are others who just will never go out and bike," said Scott Brink, public works director for Wheat Ridge. But then, he said, "there’s that huge percentage in the middle that likes to bike, that would try to get out, but thinks it isn't safe."

It’s unlikely that Gary Suydam will clip into a set of bicycle pedals again.

As he lay hospitalized in the hours after the crash, the Lakewood Police Department was gathering all his possessions, typing up an inventory of what could have been a mundane day.

They took his black riding shorts, his red backpack, his cycling gloves, his facemask and his towel, his computer programming magazine, his empty Tupperware and even his whimsical Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles lunch box.

Gary wouldn't accept the severity of his injuries for a long time. It would be months before he realized how close he had come to death, or how little hope the emergency room doctor had held.

“They said, ‘Don’t come visit him. You’re not going to like the way he looks,’” Lisa Suydam says. “For a few days, I’d try to stay away. But I’d sneak back up and see him.”

Here was this man with a wild soul, a big kid, a musician who toured with bands until his own kid was born, a skateboarder who celebrated his 50th birthday by hitting a frontside grind at the Denver Skate Park on 19th Street.

In those first weeks after the crash, he couldn’t speak because of the tube in his throat. When they taught him to spell out words, he would just spell nonsense. And even then, they didn’t know just how bad the crash was. “I didn't learn that his head was run over until the trial — the criminal trial,” Lisa says. “Nobody wanted to say how bad it was.”

Today, he cannot move his hands or lower body, so he steers a powered wheelchair with a straw in his mouth. He sleeps in the dining room of he and his wife's four-story townhouse near Sloan’s Lake.

In an interview at home, Gary’s wry sense of humor sneaked through. For example, he takes some delight in defusing people who claim he survived by a “miracle,” saying that if God was involved, then he also “micromanages the drivers of those cars, and he made them hit me, and that makes him an asshole.”

At times, though, the darkness invades. “Everything I said, ever since I’ve known Lisa — about the future — has now become a lie,” he says in a quiet moment.

“I don’t understand,” she tells him.

“We talked about what could be,” he responds quietly. “It’s OK, It’s OK,” she whispers, then turns the conversation to happier things.

A year after the crash, Gary has returned to work. He’s trying to regain movement in his arms so he can switch to joystick-driven wheelchair, or even propel the chair with his arms. “Little things show up,” he says. “I’ll accept them as they show up, when they show up.”

The Suydams’ neighbors have banded together to raise money, shovel their sidewalk and tend their lawn — an unexpected turn for the couple that used to host every neighborhood party. Their three kids, meanwhile, are home every morning and evening to help.

“I think it showed that we raised really good kids, that we must be really good parents,” Lisa says.

An accountant by trade, she takes a frank view of the future. “We’re going to have to make concessions that we've never had to or wanted to do in the past,” she says.

But they’re still together, decades after everyone said they wouldn’t work. “Because we love each other,” she says, mock-admonishing me for asking why they've stayed together all these years.

Just before the crash, they were planning a move to Europe.

They’ve always admired the way European cities are built for bikes.

"Cars in America, in general, they own the road," Gary says. And Hurwitz, the researcher agrees.

"This problem has been solved internationally," he said. The city of Amsterdam "decided several decades ago that they were going to make bicycling safe for all users. ... It can absolutely be resolved."

Piep van Heuven, Denver director of Bicycle Colorado, thinks that work could start in intersections. "Most of our bike lanes drop (at intersections)," she said. "The intersection's a free-for-all and you pick it up on the other end."

Larger lanes and islands for pedestrians would be a start, she said. But she's also taking the fight in the opposite direction: Bicycle Colorado recently launched classes that will teach drivers in 26 communities about safety around bicycles. The hope, she said, is to spare cyclists and drivers alike from another awful crash.

"Most people aren’t just drivers or people who bike. They’re both," she said. "We all have a stake in it."

But Gary's focused on a different transportation problem now.

Where once he worried about bike lanes, Gary now is painfully aware of the fact that much of Denver is not designed for people with disabilities.

Entire blocks lack sidewalks. RTD’s Access-a-Ride van service is too unreliable and slow to make crucial doctors’ appointments, he says.

So, they're thinking of moving again -- but, this time, it's to places like Arizona or Florida, where it doesn't snow and Gary might find it easier to get around. For now, watching from his window, he can’t help but notice how drivers are tempted to roll through a nearby stop sign, just to save a few seconds.

"People are in a hurry, you know?” he says. “They first of all think, 'It’ll never happen to me. I can drive this way. I can sneak through this yellow light.' They never think it can cause an accident."

Meanwhile, the Suydams have largely forgiven Chelsey Brewer. They requested that she be spared from jail time; she served community service for failure to yield the right of way. “Once again, anger only hurts the person who's angry,” Gary says.

But they’re frustrated, they said, that Stephen Tecmire — who pleaded not guilty — has moved to appeal his case, which landed him a five-year sentence.

"They could have just waited a second longer. He could have just stopped," Gary says. "None of it needed to happen.”