Tuesday was a hallowed day for those who study a certain kind of storm. In Boulder, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, or NCAR, hosted the first summit on hail ever to occur in the U.S. (and possibly the world).

Seventy percent of all storm related damage in the U.S. is caused by hail each year, said research meteorologist Ian Giammanco during a special press address. So why the hail should this be the first time in history that the scientific community has come together on this topic?

Hail is like the "Rodney Dangerfield" of extreme weather events, Giammanco said. "It doesn’t get any respect."

But it ought to. Giammanco works for the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, and he says his agency's research has found that costs associated with hail batterings each year are steadily rising.

This year, he said, will be the 11th straight year in which total dollar losses associated with hail exceeds $10 billion.

Now, there is some research that suggests climate change could make hailstones and storms bigger and more intense in the future, but Giammanco said it's not the hail that's changing and causing more damage. It's us.

Let's back up. What actually is hail?

It takes kind of a perfect storm for hail to form, said Andreas Prein, a project scientist with NCAR who also joined Giammanco on the panel.

For a hail storm (or any big, scary storm, really), you first need "high buoyancy," or highly unstable air that's rife with updrafts.

Next, "to get a really good hailstorm," he said, you need "different wind speeds at different heights."

The third ingredient: varying levels of moisture at varying heights. The fiercest storms need humidity closer to the ground and dryer air higher up.

And finally: freezing temperatures need to be close to the ground.

This all results in a vortex that sucks air and moisture into the cloud from the bottom, launches those particles high into a whirlwind of freezing, dry air, then they grow into large fragments of ice that hurl toward your windshield. Here's an illustration of the process.

The most brutal storms across the world all occur next to mountain ranges, said Kristen Rasmussen, an assistant professor at Colorado State University. She's studied these events with satellites that look at the entire globe's worth of storms at once, in three dimensions, like an enormous MRI.

"Elevated terrain warms faster than the air around it," said Andrew Heymsfield, a senior scientist at NCAR, which poises the Front Range to be a "breeding ground" for big storms.

The region has been a center of research on hail for decades. Concerns around storms were large enough in the '70s that NCAR carried out the National Hail Research Experiment in northeast Colorado to see if "cloud seeding" -- a semi-sci-fi weather-manipulation tactic -- could be used to tamp them down.

The Front Range's population boom means there's more and more stuff to pelt each hail season.

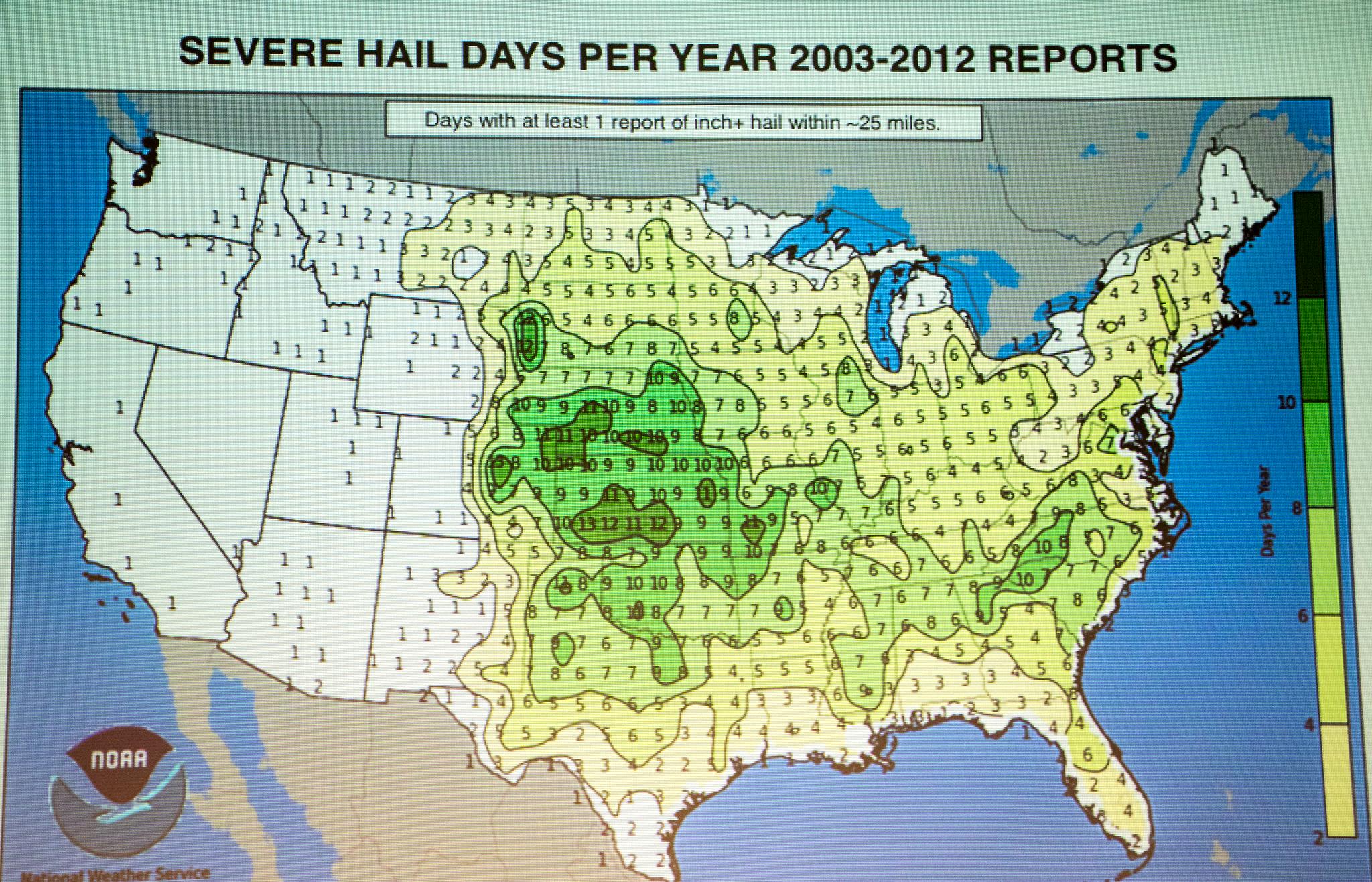

Across the country, Giammanco said, our cities are growing, and that's leading to higher costs associated with hail damage each year. These storms can be super location-specific, but they can be extremely destructive if they hit a dense area

"It’s a lot more material out there that can get damaged," he said. Houses are being built closer together, "that’s a lot bigger target," and average home sizes are also increasing.

This is true in Colorado too, said Carole Walker, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association (RMIIA), a regional group that works closely with Giammanco's nationally-focused agency.

It's not just homes that are getting bigger, she said. Cars are also becoming more expensive and are built with higher-tech features that add to a storm's overall cost.

With the exception of a tornado event in Windsor and a hailstorm in Pueblo, RMIAA's website says, the top ten most expensive hailstorms in the state all took place in the metro area. This makes sense, it continues, "because that's where the largest concentration of property in the state is located."

"We’ve always been in hail alley," Walker said, but our recent population boom has set the stage for more expensive storms.

The most costly event to date was only a year ago, on May 8, 2017, when hailstones took out skylights at the Colorado Mills Mall. It had to close and has still not fully re-opened.

Colorado ranked second in hail-related claims between 2014 and 2016 (behind Texas), and the state's claims accounted for 10 percent of all hail reports nationwide.